14th February 2018

The announcement that 5 of the 7 TV rights packages have been sold for £4.46bn, leaving the remainder “in negotiation”, has provoked an intense debate over the current state of the football in the UK.

Background

In part, the attention is understandable. The rise in Premier League revenues from domestic TV has been nothing short of a triumph for Richard Scudamore and his team. Having increased from a mere £191m in 1992 (for a five-year term) to £5.14bn for a three-year term up until yesterday’s announcement, the equivalent rate of inflation would see a pint of beer costing £65 compared to £1.44 in 1992. The last two contracts both saw increases in value of 70%.

Indeed the sheer weight of money coming into the Premier League has led to two seemingly inescapable shibboleths:

- That the quality of the Premier League is vastly ahead of other leagues

- That the economic health of the clubs themselves is sound and on a firm footing.

Reality kicks in

There is no denying that the marketing reach of the Premier League is nothing short of amazing. The prevalence of Manchester United and Chelsea football shirts in Hanoi, Hong Kong and Malaysia is just a small indication of the global appeal of the Premier League. To deny its success in purely marketing terms would be churlish.

Whether such “appeal” has translated into quality on the pitch itself is perhaps more questionable. Certainly, the funds generated by the large TV contracts have attracted players from across the globe on a scale never seen before in the English game. However, as Oliver Kay’s excellent tweet from Tuesday 13th February 2018 demonstrates, the track record of English teams in the knock-out stage of the Champions League since 2012/13 can only be described as poor if not embarrassing:

“Champs League knock-out ties won since 2012/13

- Real Madrid 17

- Bayern 11

- Barcelona, Atletico Madrid 9

- Juventus 7

- Dortmund 5

- PSG 4

- Monaco 3

- Man City, Chelsea 2

- Galatasaray, Wolfsburg, Porto, Benfica, Man Utd, Leicester 1.”

(Thanks to Oliver Kay)

When viewed through this lens, perhaps the pre-eminence of the Premier League is not as well-established as some would have you believe. Clearly the influx of “foreign talent” has not, as night follows day, led to teams from the Premier League “conquering all” against the cream of European football.

Perhaps this is cyclical? Perhaps not. Just to be clear, since 2012/13 English teams have won 6 knock-out games in the Champions League – whereas Real Madrid alone have won 17, almost three times as many!

Furthermore, a list of the best players in the world would immediately include Messi, Suarez, Ronaldo, Neymar, Coutinho and possibly Sanchez. Only one is currently gracing the Premier League. Therefore, perhaps a more sobering interpretation of the Premier League’s ability to attract the best players in the world would be appropriate at this time?

But wasn’t the Premier League also designed to improve the standard of football and thus the local talent therein?

Unfortunately, the progress of the England team can hardly be said to have been positive, having not won a game during the knock-out stage of an international tournament since 2006. Given that 22 years have passed since England’s last foray into a semi-final, the achievements of Spain, Italy and Germany frames the English Premier League in this context as a non-performer by comparison.

Club Health

Given the size of the alleged wage packets of Sanchez, Ozil, Pogba et al, it is perhaps not surprising that fans believe that the Premier League clubs are in some overwhelming equivalent of a “gold-rush.”

However, when rigorous and demanding financial metrics are applied, the picture is alarming at best. The economist Alfred Marshall who in 1890 stated the following:

“Value is created by investing capital and generating a return greater than the cost of that capital”

Alfred Marshall – 1890

Traditional accounting metrics will not satisfy the above definition. Why? For perfectly legal and long-standing reasons, the accountancy profession treats shareholder’s equity, a hugely important part of the capital of the club, as being “free.” This is turn leads to further misunderstandings regarding the economic health of the organisation (or football club in this instance). Over time, this situation leads to decisions being misaligned with the long-term economic health of the organisation.

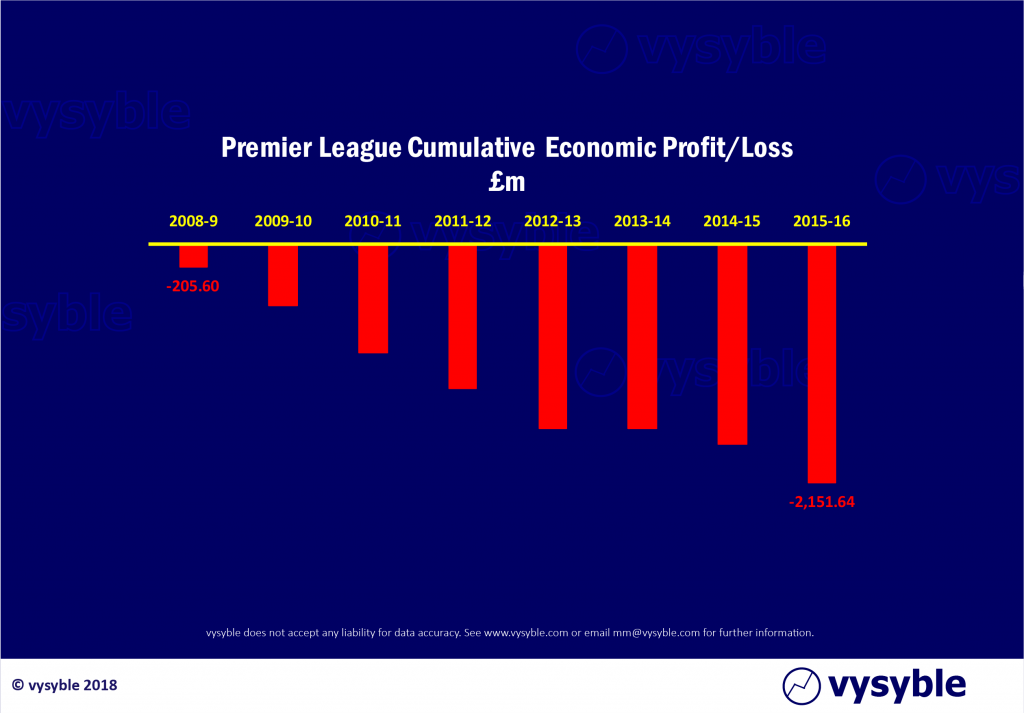

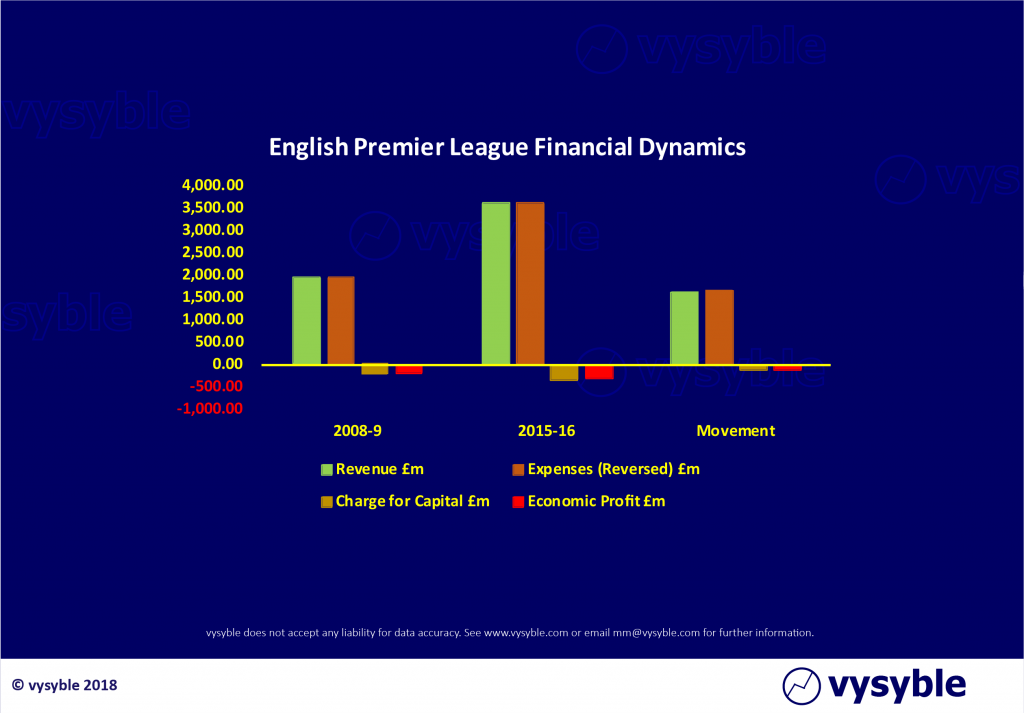

For this reason, we at vysyble have applied the economic metric defined as net operating profit after tax less a charge for all the capital used by the organisation. Our numbers have left us both alarmed and concerned for the future of the national game.

In our guest blog piece for the Soccernomics website we clearly demonstrate that ALL the revenue increases since 2009 have been frittered away in higher costs, presumably to player’s wages and fees to agents. With a couple of rare exceptions, it would be difficult to logically argue that the clubs have tried to fix the roof while the sun shines.

Industries faced with losses on this scale usually end up facing one of two futures: bad or worse. In fact, the only reason as to why many clubs are being kept afloat is principally due to the lifeboat of the massive increases in TV monies every 3 years. This, based on yesterday’s announcement, is about to change.

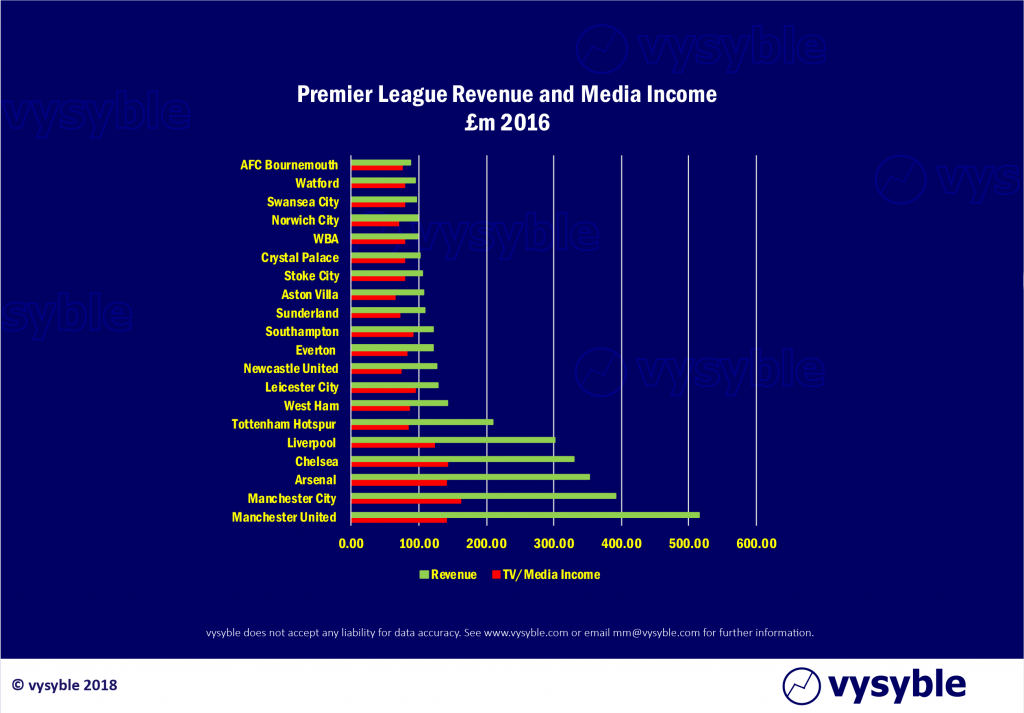

The middle and lower-ranking clubs within the Premier League rely heavily on media income, usually between 60-80% of revenue. Any perceived shortfall in the face of competitive transfer pricing and wages is going to seriously affect economic performance, operational stability and their ability to compete. Already, there is a clear divide between the top 6 clubs and the rest of the division in all these areas.

In addition, the ever-increasing economic strain of the current football agreement on Sky plc is clear (see blog of 27th July 2017). The latest announcement whereby the brakes have been applied is not a surprise to us at vysyble and on balance is a good day for Sky’s shareholders. The annual saving of £200m in the proposed new arrangement is broadly equivalent to their economic loss in 2016/17.

Looking forward

Given that the current TV deal has two years to run, with the announced new arrangement running for three years after that, there remains the distinct possibility, subject to international inflows, that the revenue profile for the Premier League will be largely flat. Against this background and with significant economic losses, the clubs will almost certainly look for new sources of profitable growth. How they go about this is subject to conjecture.

- Will the top clubs agitate further for an increased share of international media rights? We believe that they will and will probably be successful after much hand-wringing with damaging consequences for clubs outside of the top six.

- Will the balance of power between the agents and the clubs alter? The huge fees currently paid to agents is arguably a function of the vast TV monies generated since the Premier League’s inception. As the TV monies flat-line and the clubs’ economic position intensifies, along with proposed legislation from UEFA regarding transfer behaviour, the reign of the agent may be diminishing.

- Will the “39th” game concept come alive again? We believe that there is a strong chance that this idea will be re-visited as part of a renewed push to increase international income.

- What will happen to transfer values? With wages being a contractual obligation, it seems that the only way to square a demanding economic scenario is for transfer values to fall. If this happens quickly then there could be very challenging times ahead for club finance directors as asset (the players) prices fall whilst medium to longer-term debt obligations remain inconveniently fixed. This will be a “crunch” for the clubs.

- Will there be increased and renewed pressure for a breakaway league? As fans of the game, this is not a scenario that we view with unalloyed enthusiasm. However, the economic pressures are such that a breakaway league with some fix on costs must at least feature on the list of potential strategic options. There is some, admittedly anecdotal, evidence that certain American owners and investors are looking actively at this option.

15 months ago, we stated very publicly that the economics of the Premier League were extremely vulnerable to a shock such as a fall in TV income given the reliance on this revenue stream and the general behaviour of most of the clubs in their over-spending. That shock seems to have arrived. The lifeboat has failed to sail.

Also, we are not surprised that economic gravity for Sky and to a lesser extent BT has finally kicked in. The much-heralded arrival of the tech giants has not, yet, materialised but we are of the view that sooner or later they will enter this market although it might not be the “silver-bullet” that some seem to think it might be. Meanwhile in north London, Daniel Levy must be thinking that his club is in a good place given the pressures on other clubs around him amidst his prudent and economically positive stewardship of Tottenham Hotspur.

Indeed, when the fuss eventually dies down and the economic realities start to hit home, what price Newcastle United?

Finally, we do think that the authorities might have seen more of this coming had they truly understood the underlying economics of their beast. Accordingly, we advocate for a wholesale review of the Financial Fair Play ruleset, ideally with a metric that includes all the costs of doing business. The oft-quoted wages to revenue metric is frankly both primitive and in danger of sending the wrong signal about the economic health of the enterprise. Its use should be consigned to Room 101.

We also recognise that the chances of this happening are pretty much in line with England winning the next three World Cups…

vysyble