7th February 2018

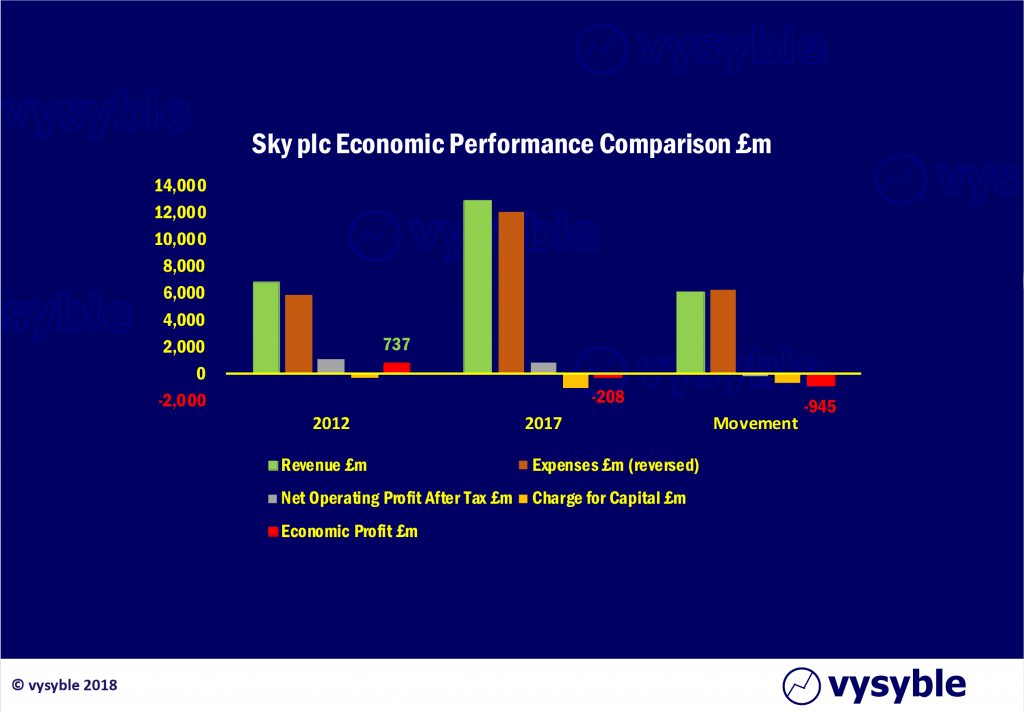

Here in the UK, the deadline for bids relating to the next English Premier League media contract for 2019-22 is imminent (8th February). Sky will no doubt be a significant part of the mix. However, as we have highlighted previously, the company has found the burden of English football to be an increasingly costly item on the balance sheet. Indeed, in our view the company’s economic performance has been significantly held back by this beast for several years.

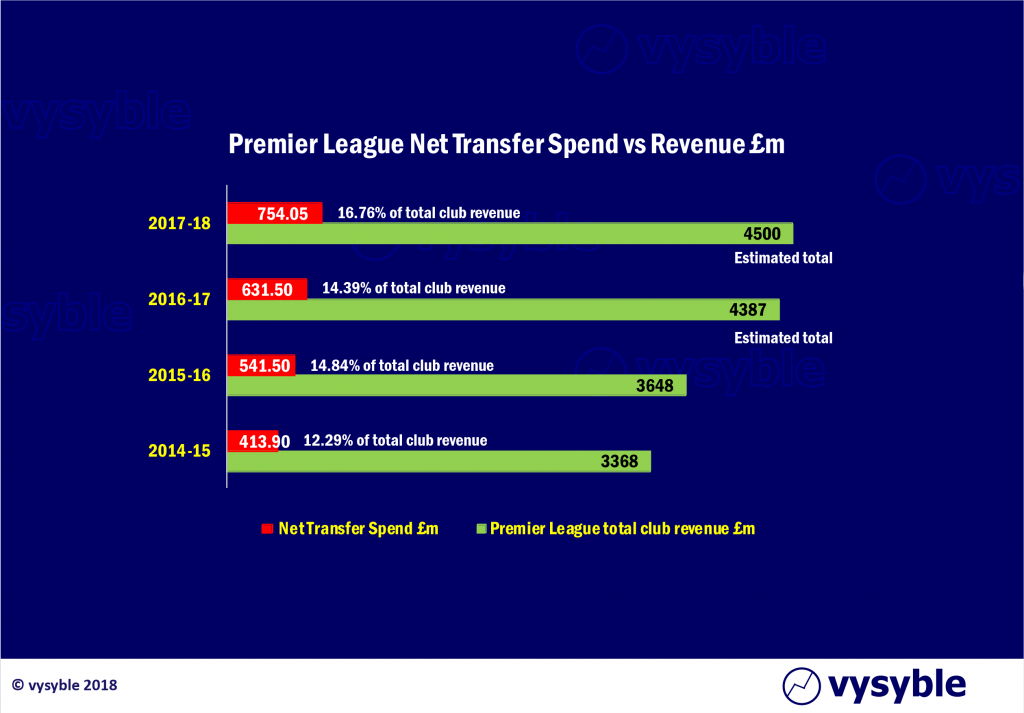

The beneficiaries of Sky’s costly generosity are, of course, the Premier League clubs. We expect to see total Premier League club revenues for the 2016-17 season, in which the latest £1.7bn per year TV contract takes effect, at around £4.38bn, an increase of just over 20% on the previous year.

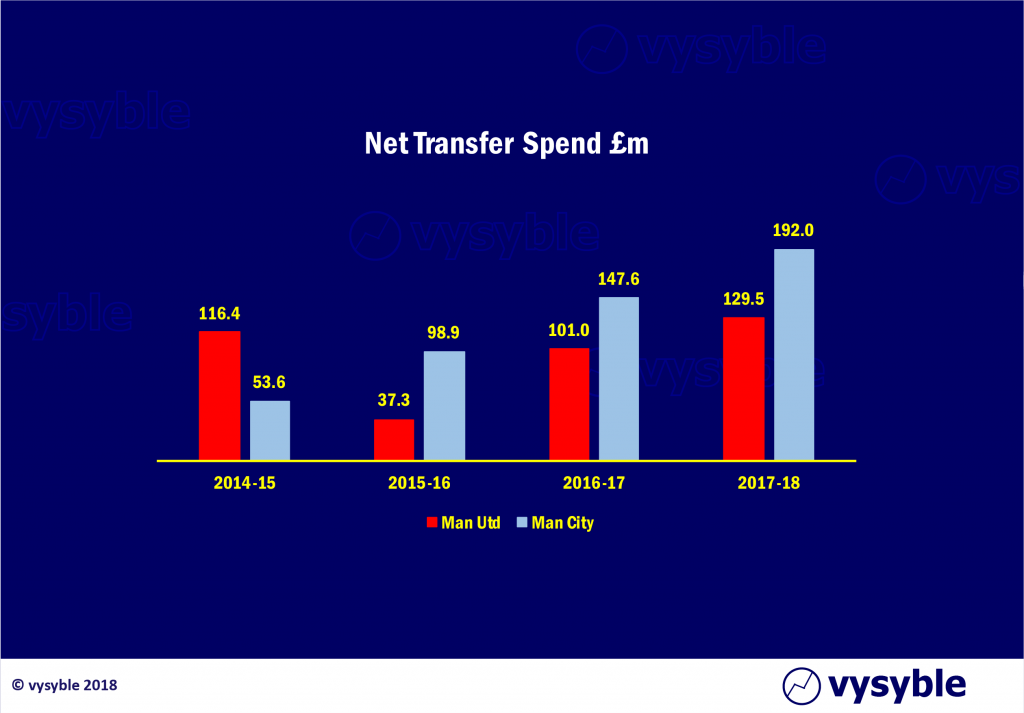

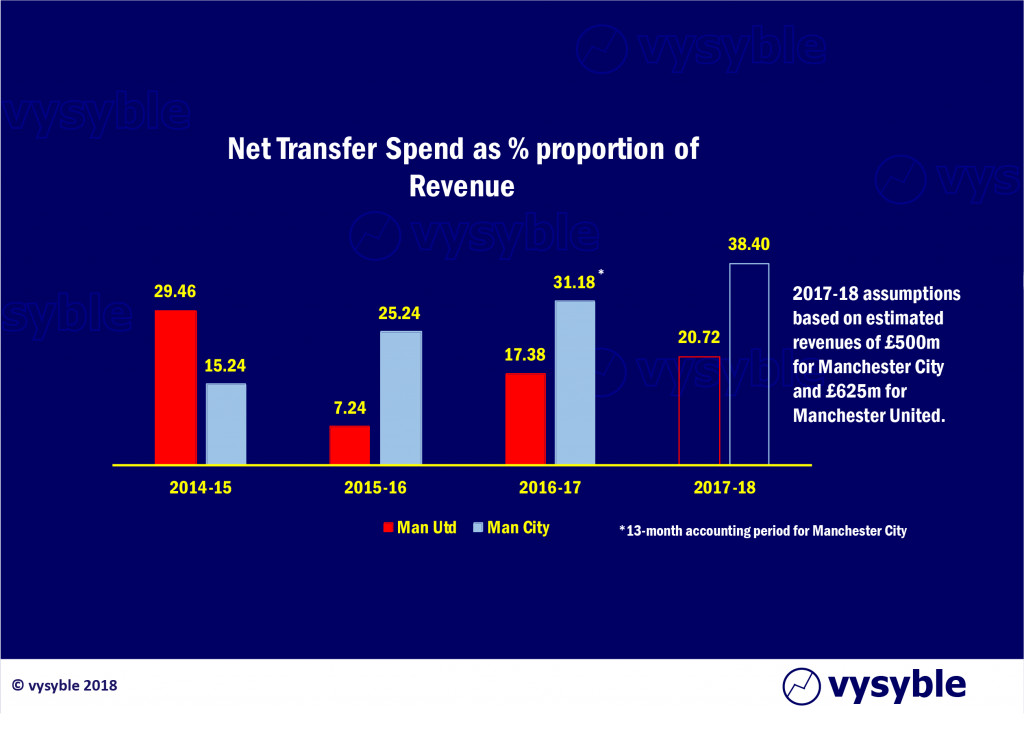

Whilst club revenues have increased significantly, so have the costs. Just one example is transfer spending. Net transfer spend for the division has increased from 12.29% of total club revenues in 2014-15 to a near-17% for the 2017-18 season, based on our forecasted revenue total of £4.5bn.

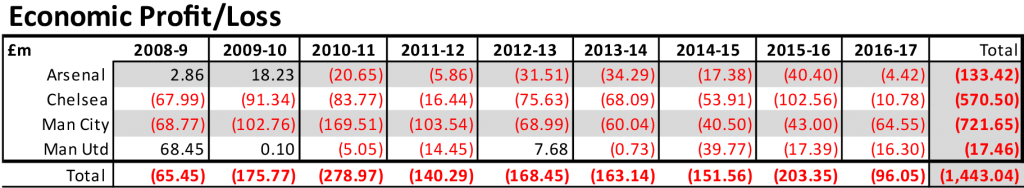

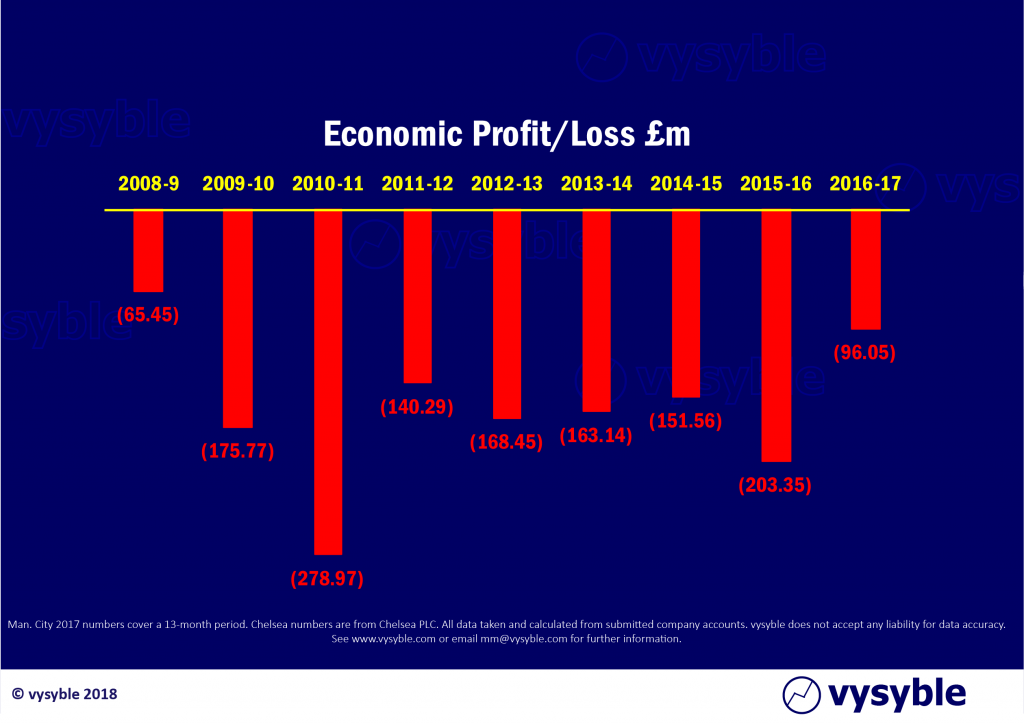

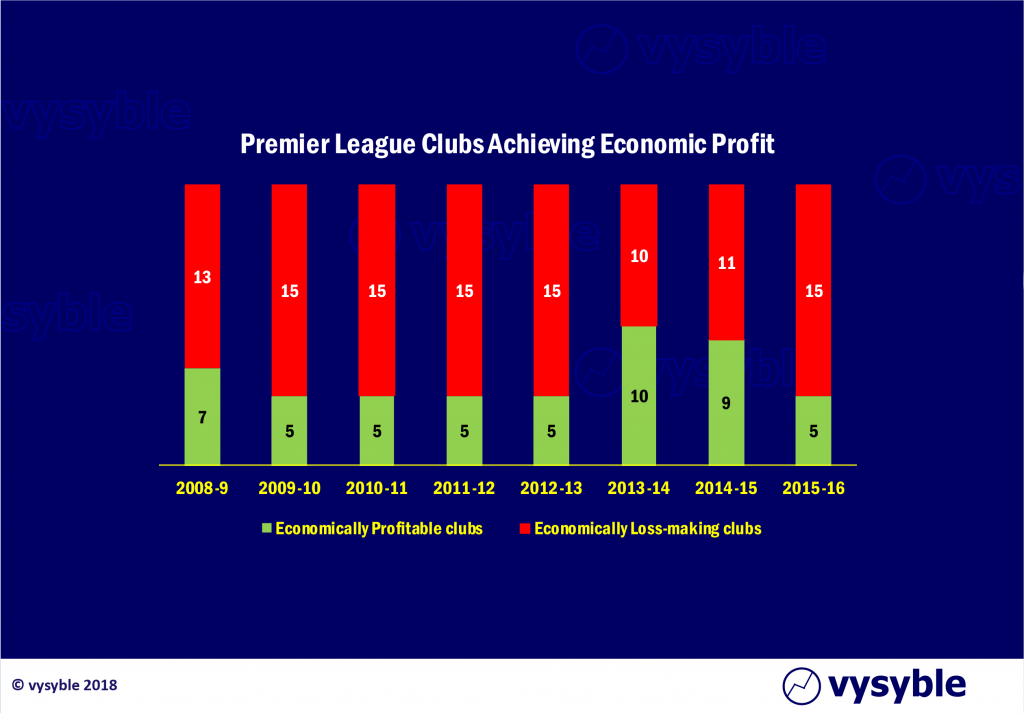

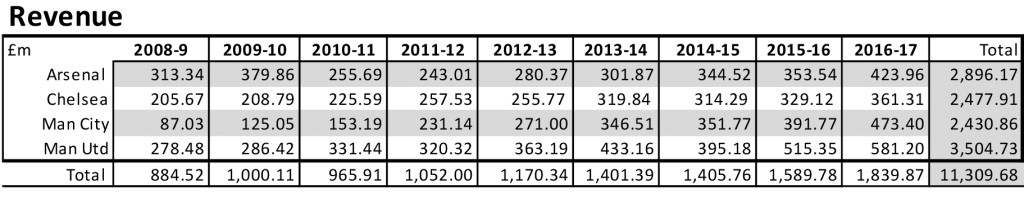

Also, the expected uplift in economic performance and profitability across the clubs has not materialised. Although at the time of writing a total of seven 2016-17 Premier League clubs have declared their accounts, only three have achieved an economic profit (Everton, Stoke City and Hull City). The remaining four – Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United – have not. Indeed, for the last four years, the ‘top 4’ have failed to achieve an economic profit whereby all costs associated with the business including tax and charges for capital are accounted for (methodology).

Note: We have used numbers taken from Chelsea plc accounts. Manchester City’s 2016-17 accounts cover a 13 month period.

Note: We have used numbers taken from Chelsea plc accounts. Manchester City’s 2016-17 accounts cover a 13 month period.

Granted, the remaining 13 clubs that have yet to release their 2016-17 accounts may have had a splendid year in terms of trading and operating activity but given previous behaviour during the first year of successive domestic TV cycles, it is unlikely.

The reason? In general, the clubs can’t spend the money quick enough. Jose Mourinho’s complaint earlier this season about the ‘noisy ‘neighbour’s spending habits does have a large element of truth to it and provides an extreme if not consistent example in recent years.

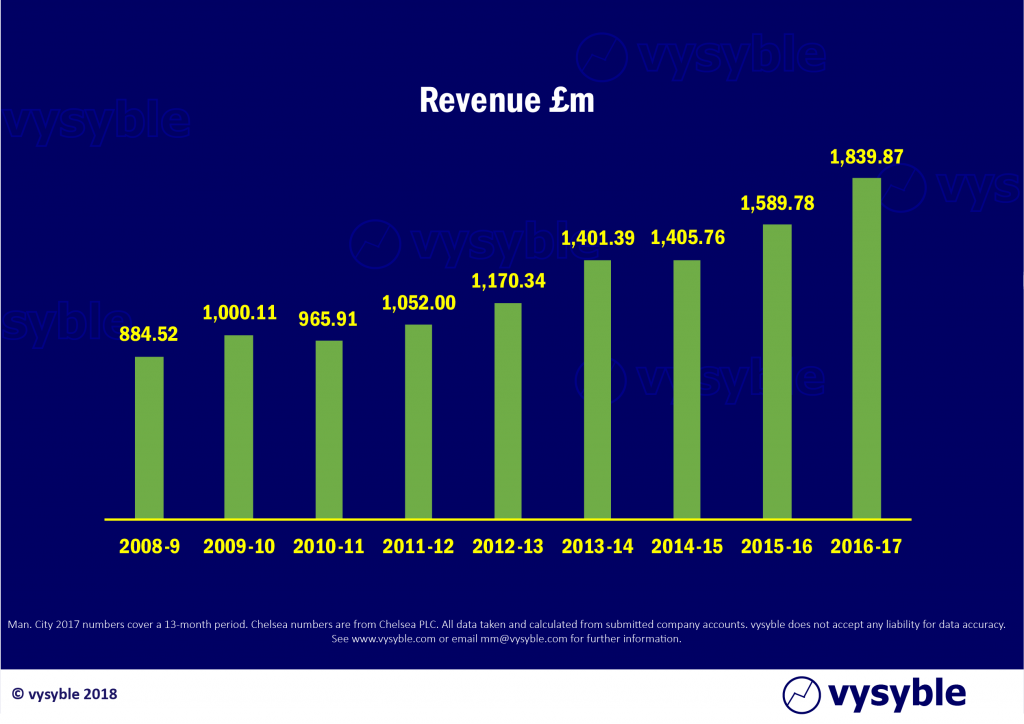

Despite a lower revenue level than Manchester United (2016-17 revenues; £473m over 13 months vs £581m), the proportion of net transfer spend by Manchester City has been increasing at a rather rapid clip, fuelled partly by TV money but mainly by the club’s generous owners. It is behaviour like this and in other areas of expenditure that has enabled Manchester City to accumulate over £720m in economic losses over the last 9 years.

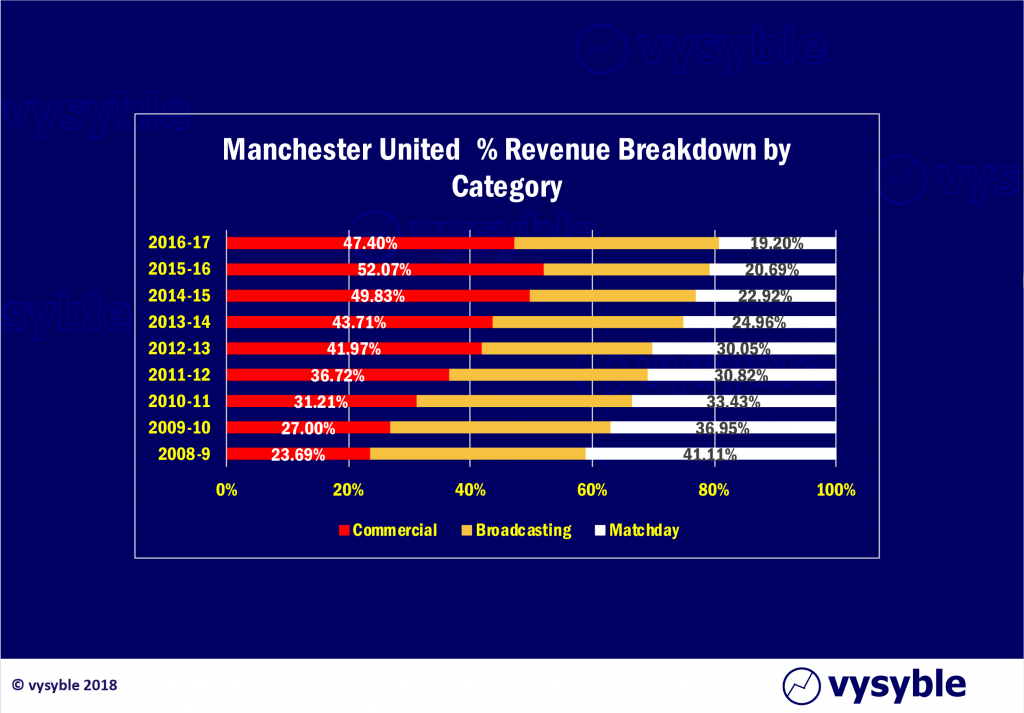

Manchester United has done well to reduce its reliance on broadcasting media to less than 35% of total revenue. No top 4 club relies on broadcasting for more than 50% of its total revenue take. This is not the case elsewhere in the division. Examples of between 60-80% of total revenue are not uncommon.

Since 2009, no single season has delivered an economically profitable division overall. Indeed, the highest number of clubs achieving an economic profit is 10 in 2013-14 which was the initial year of the previous domestic TV cycle. By the end of that 3-year term, the number of economically profitable clubs had reduced to 5.

Whatever the outcome of the latest media rights auction, the result will matter more for the clubs in the middle of the division as ranked by revenue – at least in this region of the table, economic profits are achieved albeit intermittently but more consistently than in the upper reaches. The risk is that if there is a pause in media revenue growth, these clubs will find themselves operating beyond their economic and financial safety limits. The damage could be considerable.

And yet the Premier League still attracts attention with Amazon, Facebook and Liberty Media all rumoured to be hovering around the prospect of entering the fray. The problem is that Sky has been there for 25 years and can’t make any money from it. What are the prospects of anyone else doing the same? Consider also BT’s falling new customer numbers for its own TV service and the cost of football becomes highly questionable.

For the top clubs, the value of the domestic TV contract is becoming less important. The key growth driver, as Manchester United has proven and Manchester City is exploiting with increasing efficiency, is not broadcast but commercial revenue with a strong international element.

Yes, local media exposure matters but from a strategic sense there is a whole new world out there to exploit. The exotic pre-season tours, competitions and friendlies all provide the next marketing opportunity. Home is done. It is an exhausted market. It is time to move on.

Even with the growth from international media rights, broadcast revenues as a percentage of the overall revenue take have remained relatively static across the top 4 clubs. It is matchday revenue that has given way. But as we have seen from the last 9 years of operation, the economic result is consistently on the wrong side of the line.

And so, the suspicion remains that the top 4, along with Spurs and Liverpool, have their eye on more lucrative revenue-generation schemes. The attempted but failed cash-grab over their share of Premier League international media rights suggests a longer-term push towards separation. The European Super League concept hasn’t gone away. The missing link is that it needs a supportive broadcaster with the financial and technological means to deliver it into the millions of homes, bars, restaurants and sports clubs around the world, live. The Grand Tour followed by Barcelona vs Manchester United. Prime-time.

The next local TV deal might just provide the excuse for such action.

vysyble