12th April 2018

“We’re flawed because we want so much more. We’re ruined because we get these things and wish for what we had.” — Don Draper, partner in the fictional Sterling Cooper advertising agency.

The above quote is taken from the Mad Men series which charted the trials and tribulations of a Madison Avenue advertising agency as the partners and employees negotiated the twists, turns and social upheavals of the 1960s.

The advertising agency ‘model’ as it was then consisted of creative and media buying with a smattering of in-house research. Major consumer research studies were usually conducted by specialist research companies. Many agencies tended to focus on a creative specialism eg print or TV. Public Relations was a separate and insular business sector. Thus the ‘communications’ ecosystem was a fragmented and highly inefficient challenge for major advertisers in terms of operational and cost management, particularly for multi-national companies where the duplication of effort and skills from various sub-contractors and suppliers made herding cats look easy.

Martin Sorrell changed all that. His vision was to service multi-national clients with the complete communication package including research, creative, media buying, Public Relations, evaluation and even audience measurement under one roof – the one-stop shop. After a turbulent transformation into the advertising and communications markets (buying JWT, a global recession and the subsequent heavy cost of acquiring Ogilvy & Mather), the manufacturer of supermarket trolleys and baskets known as Wire and Plastic Products Ltd eventually grew into the multi-national, multi-faceted behemoth that we know today. Consequently, Sir Martin Sorrell is quite rightly recognised as one of the most influential figures in the history of advertising.

Today, WPP is making headlines but not necessarily for the right reasons. Indeed, the rumblings of discontent have been evident since 2012 when Sir Martin’s £12m+ pay award was rejected by shareholders. The general impression is that the boardroom has not been a happy place for some time. The evidence strongly suggests that the private equity-level remuneration that Sir Martin has sought is not being matched by private equity-level performance.

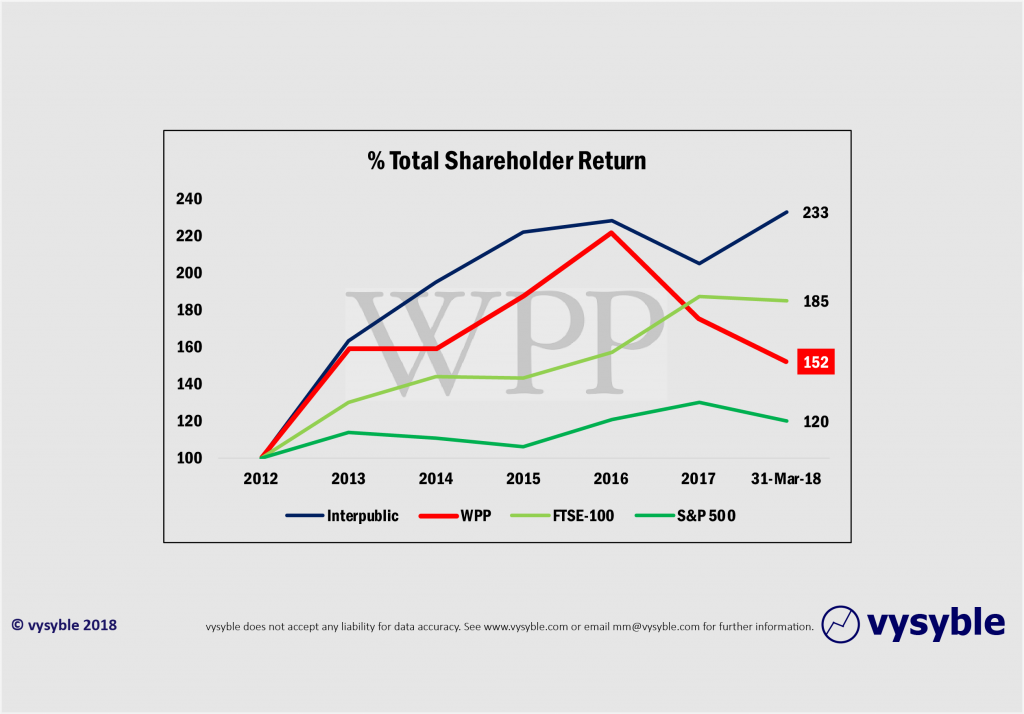

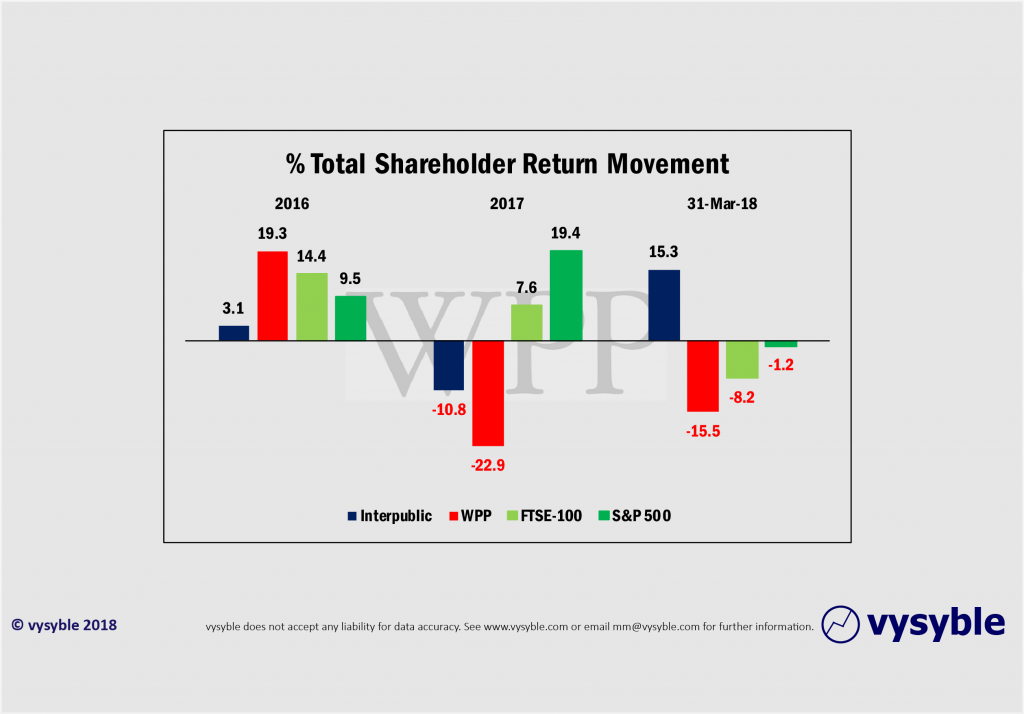

Certainly, shareholders have seen a level of under-performance relative to peers in recent years.

Total Shareholder Return (TSR) re-based to 100 through to the end March 2018

Whilst the advertising/communications sector is particularly sensitive to the cyclical nature of the global economy, WPP’s total shareholder return performance has declined well ahead of the markets in a period of rising interest rates and increasing noise around global trading tariffs. From 2016, the recent underperformance when compared with Interpublic – a close competitor – is marked.

The irony that permeates the current position is at odds with the very core competency of the WPP empire – communication.

The latest WPP company report offers the following;

‘Our goal remains to be the world’s most admired, creative and respected communications services advisor to global, multinational, regional and local companies. To that end, we have four core strategic priorities:

- Advance the practice of ‘horizontality’ (connected know-how) by ensuring our people work together for the maximum benefit of clients: through cross-Group Communities and Practices, Global Client Teams, and Regional, Sub-Regional and Country Managers.

- Increase the combined geographic share of revenues from the faster-growing markets of Asia Pacific, Latin America, Africa & Middle East and Central & Eastern Europe to 40-45% of revenues.

- Increase the share of revenues from new media to 40-45% of revenues.

- Maintain the share of more measurable advertising and marketing services – such as data investment management and direct, digital and interactive – at 50% of revenues, with a focus on the application of technology, data and content.

And so, we find ourselves somewhat puzzled by the arch-communicator regarding the ‘message’. For example, where is the strategic prioritisation in terms of shareholder returns? Indeed, for whose benefit is the company being run for, if not for the investors?

Furthermore, how do clients and shareholders measure or benchmark ‘maximum benefit’?

Indeed, the statisticians at subsidiary companies Kantar TNS and Millward Brown must be tearing their hair out at the arbitrary 40-45% share of revenues from everywhere other than the USA. A 5% differential can be anywhere between £0 and £760m…

Finally, the 50% revenue share from the advertising and marketing services element of the business does not address the question of the proportion of that revenue which is profitable? Certainly, Kantar Futures would have us believe that all revenue growth is good (Follow the Money, 2018) because demand delivers dollars etc. Of course, taking an economic perspective negates much of demand-driven dynamics when it comes to revenue growth. Value engines within business operations need to be carefully nurtured and managed with consistent measurement and sensible strategic deployment. Blind revenue growth is the root of value destruction and ultimate elimination eg Enron, Carillion et al. Perhaps not quite the sound advice to be giving to clients.

A business based around the art of communication seems to have lost its way. Our view is that the turmoil surrounding Sir Martin’s tenure is more of a strategic shift than a disagreement about expenses. The unique appeal of the one-stop shop model is losing its allure as others replicate it (Dentsu, Interpublic, Omnicom and Publicis) or even execute it in a better form than the originator. For some, the local independent creative/media shop provides a more nuanced approach to the demands of single country markets.

For the one-stop shop providers the era of creating value through acquisition coupled with fierce cost control is over. Those private equity-level returns have been nibbled away by diminished acquisition opportunities and the ingress of social media as stand-alone advertising platforms. More recently, the digitalisation of advertising has enabled some lawn-parking by the global consultative herd. The conversation surrounding WPP is not one of value creation for the shareholder. The message that emerges is muddled and difficult to understand. The capital markets seem to agree.

And as the fictional Don Draper said in a pitch to an advertising prospect, ‘If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation’. Until Sir Martin’s position is clarified, that might be difficult.

vysyble