18th March 2024

Sometimes, pivotal moments take place right in front of our eyes but do not become apparent until sometime afterwards. In our opinion, the recent refusal of the Premier League clubs to endorse a new financial subsidy package aimed to assist the lower leagues of English football is a pivotal moment.

Here is a fact to start with:

Premier League clubs are largely economically-loss making enterprises despite achieving record revenues season by season.

Football is unusual in that it has been considered by successive Governments to be a ‘business’ and thus subject to all the laws and demands (usually tax, which has got a few clubs into trouble over the years) that any other business in England and Wales must adhere to. Despite this, football is also unusual as mergers and acquisitions at the professional level do not happen and are relatively rare in the lower leagues and beyond. Consequently, the usual industry market dynamics that we observe elsewhere in the commercial world simply do not occur.

The monetary narrative regarding football has concentrated on increasingly record revenues, the greed of clubs and owners and various reports on the excessive spending habits of Premier league players. It makes for good reading but is far removed from the economic reality. Our use of the economic profit metric has delivered some prescient and insightful observations that so far have not been proven wrong (Super League, club financial distress events etc.) and which paint a very different picture than the one that various promoters of the game and others will have you believe.

For those of you who are familiar with our work, the following will serve as a refresher before we get into the meat of recent events. For those of you who are not familiar with our work, the following text will explain the economic profit metric and the consequences of dismissing it from a strategic and business performance perspective.

A brief summary of events:

As clubs continued to lose money via high payments to players and their agents together with an increasingly expensive transfer market, a form of financial restraint known as Financial Fair Play was enacted by UEFA for clubs participating in European competition. The idea was to reign in free-spending clubs and imbue a sense of even competition.

The Premier League enacted a similar scheme although it could be argued that it was loosely applied until the Super League launch which in itself was the result of continuing losses and as a means for the clubs in question to find a route to profit. Prior to the Super League launch, Covid had hit the world and upended the already fragile financial status of England’s leading clubs who were finding it difficult to balance losses against an increasing cost of competitiveness. A dangerous cocktail of poor or misplaced oversight, lax application of the financial rules and a very loose interpretation of some of the Covid-related allowances enabled clubs to subsequently spend even more with less income.

The key reaction to the Super League debacle came from HM Government which is currently in the process of establishing an Independent Regulator for football following the Crouch review. Clearly, this goes against the wishes of the relatively free-spending mix of Premier League clubs, the ownership of which is largely based from outside of the UK. Yet, in spite of this, the Premier League administration, in an attempt to deny the need for independent regulation, appears to have taken the decision to apply its financial rules in the strictest possible terms.

Consequently, it came as no surprise for Everton to be first in line for a rebuke given its high level of losses by most measures and its relatively low revenue.

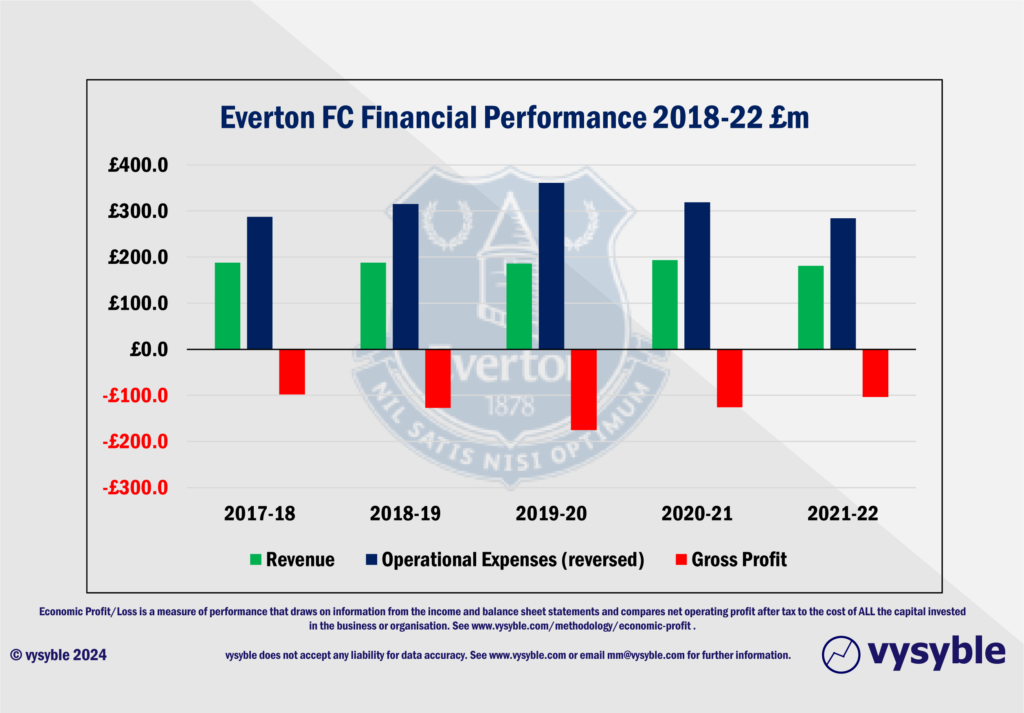

The graphic above reveals Everton’s Revenue, Cost of sales, and Gross Profit performance over the 5-year period 2018-2022. Revenues over the period totalled £936.9m with costs of £1,566.4m producing a Gross Loss of £629.5m.

In other words, at the ‘Gross’ level, for every £1 of revenue the club is losing 67p. The club generated £229.4m in surpluses on player sales (again over the 5-year period) which reduced the loss before tax and finance to £400.1m, which is a loss of 42p for every £1 of revenue.

Several prominent commentators have described the original 10-point penalty conferred on Everton for its financial ‘misdemeanours’, which was subsequently reduced to 6, as harsh. We prefer not to comment either way. However, what does seem obvious to us is that even before we get to relatively sophisticated metrics like Economic Profit, at a top-line level the financial and economic situation of the club is simply not sustainable under the current modus operandi.

Despite the rich heritage of Everton FC, the risk of implosion is real and is further compounded by the lengthy and somewhat ambitious attempt by the US-based 777 Partners to acquire the club with numerous questions raised in the media regarding viability, financial provenance and an already questionable track record in football club ownership in Europe. The limit to this financial disaster cannot be too far away…

Everton might be extreme, but they are not alone.

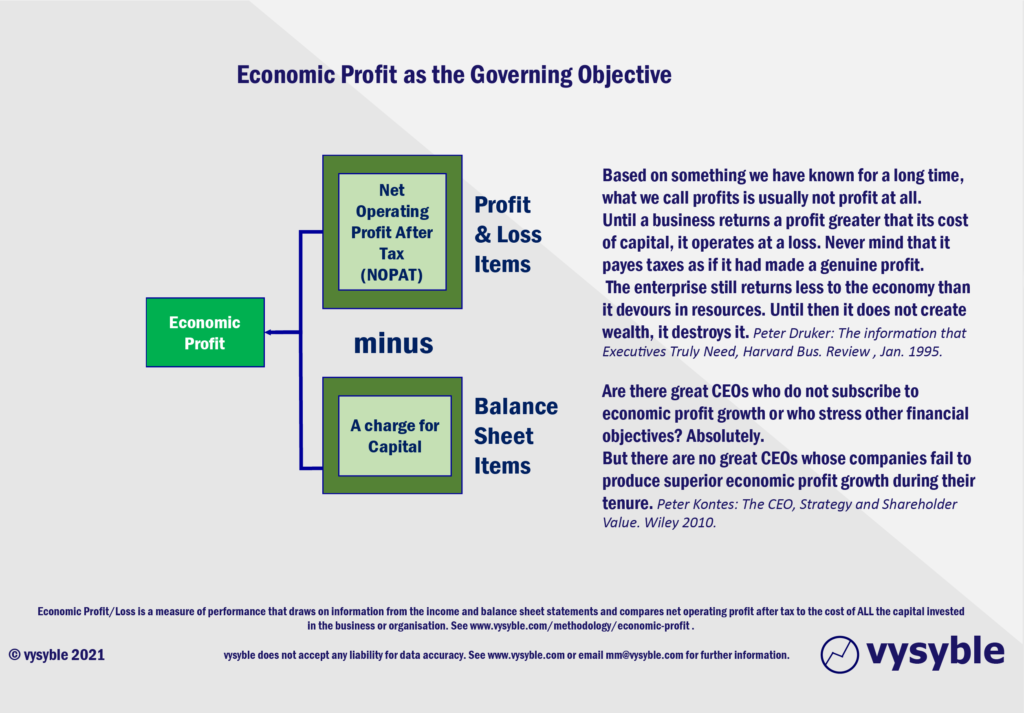

Regular readers or followers of or work will know that we advocate the use of economic profit to understand value creation and destruction at both the corporate and the industry level. To our mind the metric is defined as net operating profit less a charge for ALL the capital used by the organisation (including equity capital) and has a signalling advantage over accounting data and even cash flow.

More importantly, it incorporates the following:

- It aligns with Alfred Marshall’s definition of Value Creation – “value is created by investing capital and generating a return greater than the cost of that capital” – Principles of Economics; Alfred Marshall – 1890

- It includes all the costs of doing business as equity capital is not free. Modigliani and Miller won the Nobel Prize for Economics for essentially proving this very point.

It is the real ‘bottom line’ for the business and it is now used extensively by credible consultancies, including McKinsey & Goldman Sachs, to measure corporate performance.

“It is not too strong a statement to say that, without EP measures, a proper managerial understanding of the strategic position of a business and the strategic options it faces would be nearly impossible.”

From “The CEO, Strategy, and Shareholder Value: Making the Choices That Maximize Company Performance” by Peter Kontes – Wiley 2010

“Creating economic profit is the single most important driver of the stock price of the Coca-Cola company.”

Roberto Goizueta, former Chairman and CEO of the Coca-Cola Company

“The object of any business is to create, maximize, and defend economic rent. Rent is what is left over after all the factors of production employed in a business or activity – including the providers of equity capital – have been paid.

The term “profit” includes both the cost of equity and the added value which the firm creates.

That is responsible for many of the ways in which profit is a misleading indicator of company performance – as, for example, when firms increase profit but subtract value by reinvesting at less than the cost of capital or enhance earnings per share without adding value by acquiring firms on less elevated price / earnings multiples.

Economists talk about rent because the central analytic concept dates from David Ricardo, who lived almost two centuries ago in an environment in which the cultivation of agricultural land was the principal commercial activity. The analogue between Ricardo’s approach and the assessment of the competitive advantage of firms remains an instructive one.”

John Kay – The Business of Economics

Oxford University Press – 1996

Of course, not everyone agrees…

“Economic profit” is GAP accounting on steroids. Totally made up and meaningless.”

Mike Ozanian, Forbes Journalist via a tweet – 23rd August 2022

It is fair to say that we are more aligned with Peter Drucker, Peter Kontes, John Kay, Roberto Goizueta, the French economist Ricardo, McKinsey and Goldman Sachs than we are with certain sections of the media.

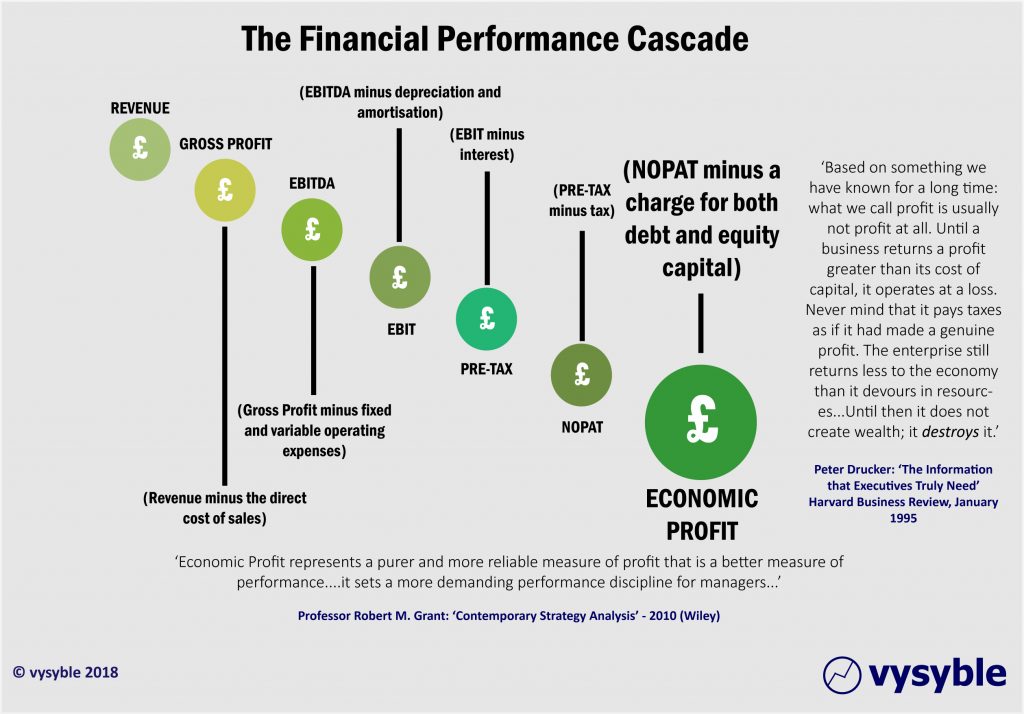

Set out below are the steps moving from an accounting to an economic perspective.

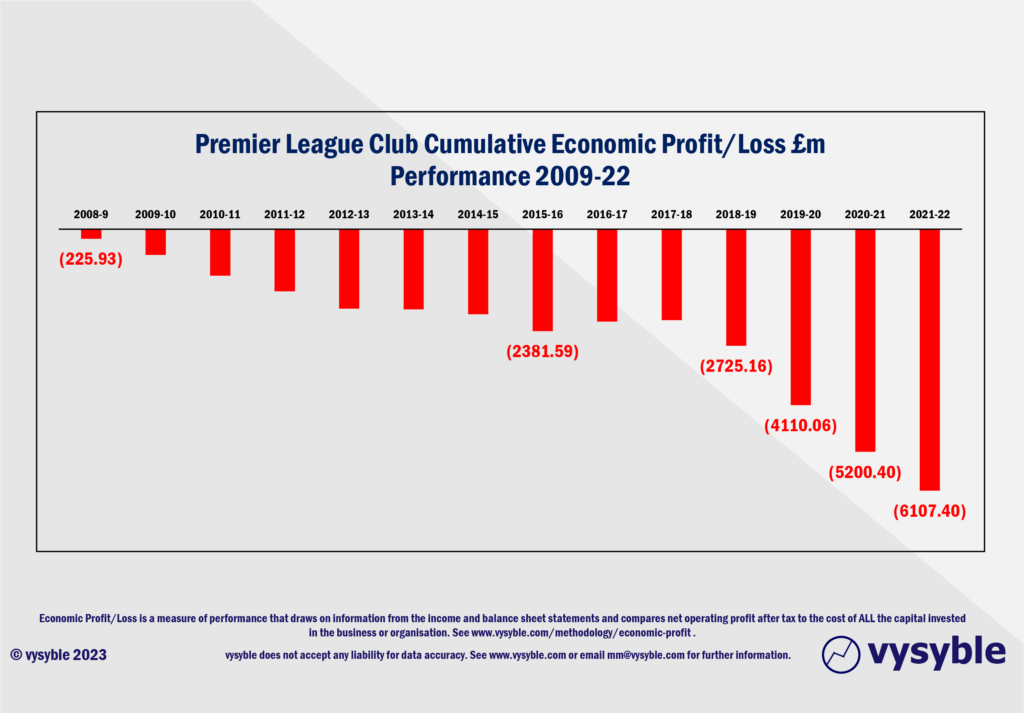

So, to establish value creation and destruction over time, we need to apply the economic profit formula to all the clubs competing in the Premier League on an annual basis. This is what we see over the period 2008-9 through to 2021-22:

Sadly, and regrettably, despite a level of revenue growth that most industries can only dream of, we observe an ongoing picture of accelerating value destruction in the form of sizeable Economic losses. Since 2009, Premier League clubs have earned £50.1bn in revenue but have also destroyed value as measured by the economic profit/loss calculation to the tune of £6.1bn.

Whilst there may be other benefits, the notion that owning a Premier League club is some sort of economic ladder to unbridled riches is simply not underpinned by any credible evidence, notwithstanding a number of long-standing myths regarding the financial and economic situation of the Premier League, some of which we will address shortly.

The above picture demonstrates why the Super League initiative came about at the time that it did. Many misinformed commentators (working on the misapprehension that revenue was a sound indicator of wealth creation) believed that the clubs in question were being ‘greedy’ rather than seeking longer-term survival through higher economic returns. To our mind this is an understandable but nonetheless a fundamental mistake.

The fact is that over a prolonged period the clubs were (and still are) destroying epic amounts of value and we know from experience of other companies, organisations and indeed industries that this rarely ends well. For organisations operating in an environment where economic losses predominate, the following quote and the implications for the beautiful game are a concern to us:

“For businesses that participate in very negative EP markets (economic losses), like airlines and paper manufacturing, operating below the zero-EP threshold almost of the time is the norm. There is very little uncertainty to be managed in these businesses. In terms of their expected returns on equity and their ability to self-finance, there are only two outcomes – bad and worse. Not only will a majority of these businesses fail to create shareholder value, but there is no balance sheet strong enough to protect most of them from eventual takeover, restructuring or insolvency.”

Peter Kontes – The CEO, Strategy and Shareholder Value – Wiley (2010)

Note the emphasis within the quote regarding the inability to ‘self-finance’. Many of our top clubs including Manchester City, Chelsea and more recently Newcastle United (amongst others) have business models predicated on funding from multi-billionaire benefactors rather than, for want of a better phrase, internally generated wealth.

In addition, two of the normal mechanisms for markets to correct themselves, namely takeover and restructuring are simply not available within the traditions of the beautiful game. One shudders at the potential reaction if (say) Liverpool FC were to make a move to acquire a clearly financially and economically challenged Everton.

Furthermore, when clubs have been exposed to the harsh economic realities and expectations of the capital markets via an equity or share issue, the results for the clubs in question and their shareholders have been disappointing if not disastrous.

At time of writing, even after an enthusiastic acquisition by Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s INEOS of 27% of Manchester United which apparently valued the club at £5.0bn, the share price has dropped back to $14.37. Thus, thirteen and a half years since the Initial Public Offering (IPO) on 10th August 2010 at $14.00 per share, the return is 37 cents or the equivalent of 2.6%.

Had the Man Utd share followed the trajectory of the capital markets, then one would expect the share price to be north of $38…In other words, the combined wisdom of millions of investors who review the shares daily is that the economic case for Man Utd is at best ‘challenged’ and the disconcerting evidence from the capital markets indicates that the operation which describes itself as the biggest club on the planet produces returns for shareholders that can be charitably described as ‘disappointing’.

Nonetheless, on a broader level we are puzzled by statements like this:

‘…profitable performance and strengthening balance sheets, that looked so impossible a decade ago, are now the norm.’

Deloitte – 2018 Annual Review of Football Finance…

One might wonder if the statement from Deloitte was rooted in economic reality. Indeed, the comment from the Premier League’s auditor of choice raises the question as to why the Premier League feels the need to implement any form of Financial Fair Play if ‘profitable performance and strengthening balance sheets’ were indeed becoming the norm…

Why do some commentators struggle with economic profit and its signal?

The typical definition of “economic profit” as outlined on Wikipedia (and elsewhere) can cause confusion:

“An economic profit is the difference between the revenue received from sales and the explicit costs of producing its goods and services, as well as any opportunity costs.”

Some people have a problem with the concept of ‘opportunity cost.’ In practice, this is less of an issue than one might initially think. If someone goes to IKEA, say, and buys a dining room table for £750 then the opportunity cost of that purchase is simply £750.

The opportunity cost in the highlighted definition often refers to the cost of equity capital which is calculated using the Nobel prize-winning formula taken from the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The CAPM tells us that this is a cost to the business or organisation. In other words, equity capital is funding the business in much the same way as a loan would or other methods of ‘finance’.

Irrespective of what the accountants may wish you to believe, equity capital is not a free ride. Those who continue to disagree with this would do well to refer to the many quotes and explanations from Warren Buffet about the role of capital and how it affects the performance perspective of a business.

The notion that somehow the economic profit metric is not suitable to football is often a thinly veiled ‘avoidance tactic’ because the economic profit signal is revealing one or two uncomfortable realities.

Economic profit has underpinned strategy development in industries ranging from Banking, Pharmaceuticals, Soft-drink provision, Retailing, Insurance, Real-Estate, Heavy Engineering et al.

The measure is one that agrees with Alfred Marshall’s prescient definition of Value Creation and has been adopted by many ultimately successful leaders in business including Roberto Goizueta at Coca-Cola, Sir Brian Pitman at Lloyd’s Bank, Sir John Sunderland at Cadbury Schweppes, Jim Kilts at Gillette…

The idea that a metric which encompasses all the costs of doing business is somehow not suitable for examining the economics and financial performance of football clubs is, from our perspective, simply the preserve of the uninformed and unthinking who seemingly prefer the status quo and are reluctant to face up to the economic realities and challenges facing the beautiful game. Indeed, and sadly, such a reluctance can only result in reactionary upheaval when the financial pressures become too great to bear.

A deeply held and widespread view that conflates revenue with value or wealth generation or indeed the health of the organisation more generally.

This ridiculous notion is given further credence by the annual publication of a list of European club revenue numbers which in turn is given additional and bogus credibility from commentators who really ought to know better…

“FC Barcelona has become the world’s richest football club for the first time, thanks to recent changes to the Catalan team’s merchandising business that has provided a financial edge over its peers.” – FT Jan 14, 2020

Reality = FC Barcelona is believed to be 900m euros in debt with numerous media outlets reporting significant financial difficulty at the club. Revenue does not equal wealth.

“World’s richest football clubs 2021: Barcelona top Deloitte Football Money League ahead of Real Madrid while Bayern Munich overtake Manchester United” – City AM

“Which are the world’s richest football clubs in 2021?” – Goal.com

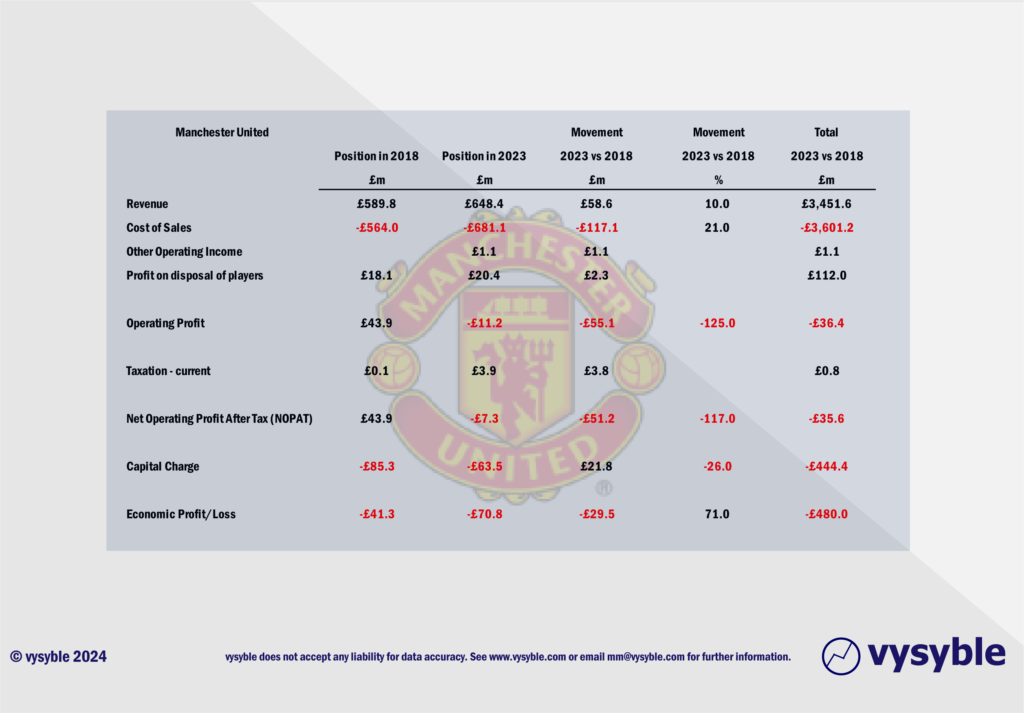

Set out below is an example using the published numbers of Manchester United. We see revenue in 2018 coming in at £589.76m per annum and rising to £648.4m in 2023; an increase of £58.64m or 10%. Viewed through this revenue lens in isolation, progress looks encouraging.

Unfortunately, over the same period, cost of sales has risen by 21% from £564.01m in 2018 to £681.12m in 2023. In other words, the increase in the revenue has been eclipsed by the increase in the cost base.

Operating Profit over the six-year period 2018-23 (inclusive) actually reveals a loss of £36.41m. When the charge for capital and taxation is included, the resulting economic loss over the period reveals a £480.04m deficit; the club is losing vast amounts of money when all costs are considered.

Manchester United is by no means an isolated example. Set out below is a similar schedule for Arsenal FC…

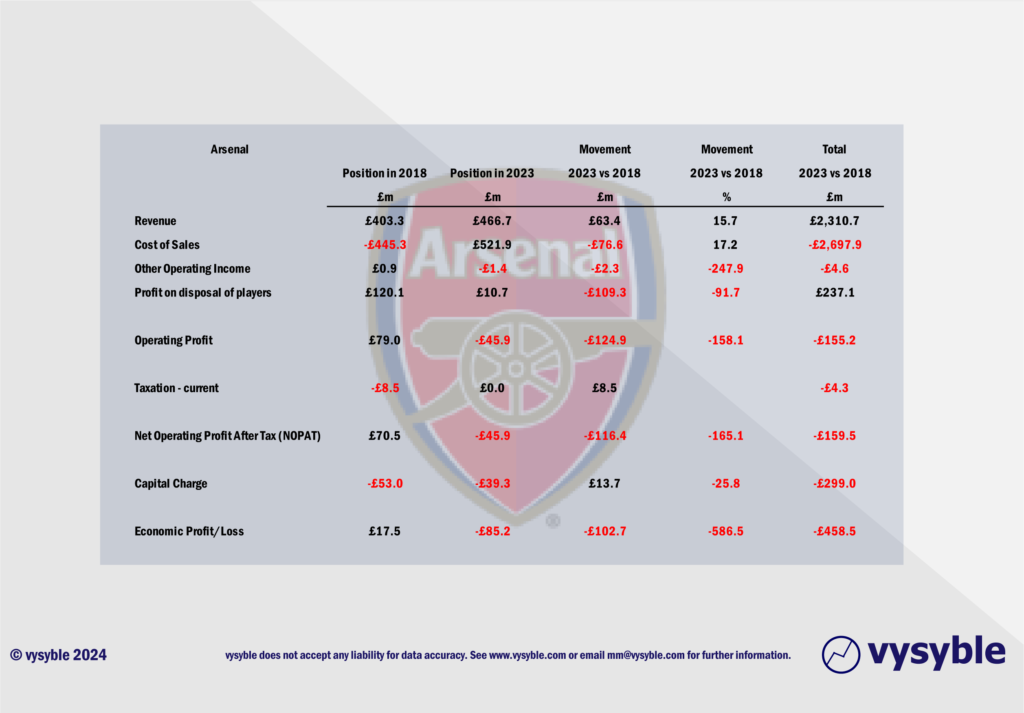

In the above example, we see Arsenal’s revenue rising from £403.27m per annum in 2018 to £466.69m per annum in 2023; an increase of 15.7% or £63.42m. Total revenues over the six-year period 2018 through to 2023 totalled £2,310.17m. Again, like the Manchester United example, the revenue perspective would appear to be highly encouraging.

Unfortunately, the club’s operating expenses have risen from £445.28m in 2018 to £521.93m in 2023 which is an increase of 17.2% or £76.65m. Operating expenses over the period 2018 through to 2023 totalled £2,697.88m which, of course, far surpasses the revenue number over the same period of £2,310.17m. The resulting economic loss over the period was £458.46m.

And another example comes in the form of Aston Villa…

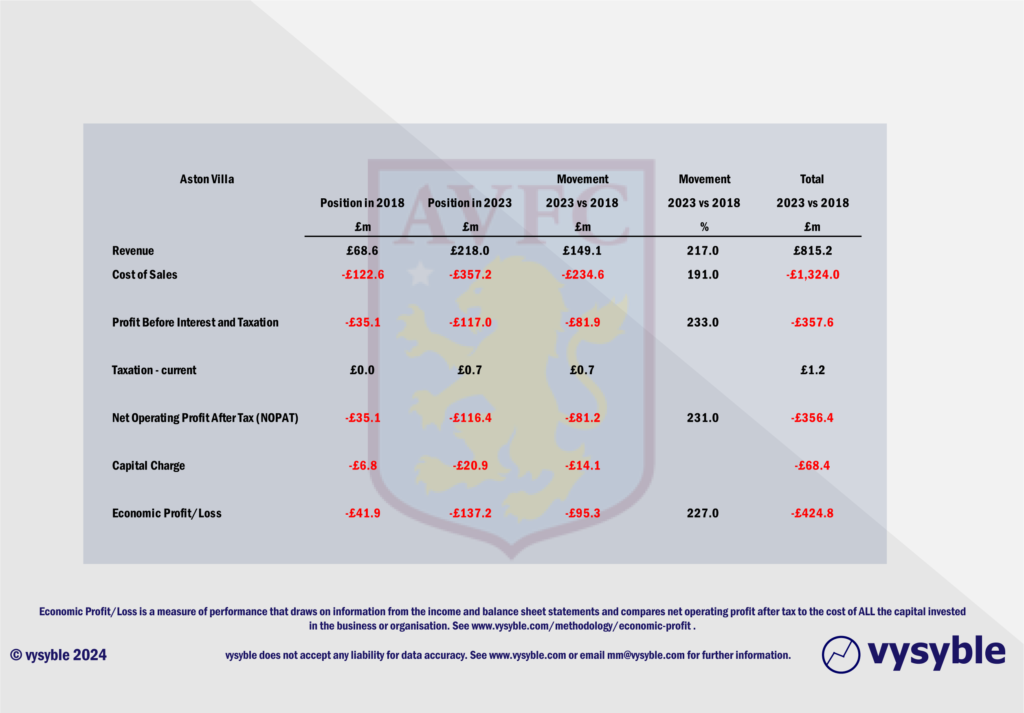

Here again, revenue between 2018 and 2023 has risen by £146.09m or 217%. However, expenses have risen from £122.62m in 2018 to £357.18min 2023 which is an increase of £234.56m per annum. Consequently, profit before interest and tax has fallen from a loss of £35.14m in 2018 to £117.03m in 2023. This is an increase in the deficit of £81.89m or 233%.

Again, the economic loss for the six-year period comes in at £424.79m.

We could go on but can we at least agree that revenue when viewed in isolation is a poor indicator of the underlying economics at play, largely because all the costs of generating a given revenue are excluded. Such a perspective can be highly damaging to the health of the club and can sway decisions by the Board of Directors which could ultimately destroy value rather than creating it.

The use of EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) compromises the economic picture.

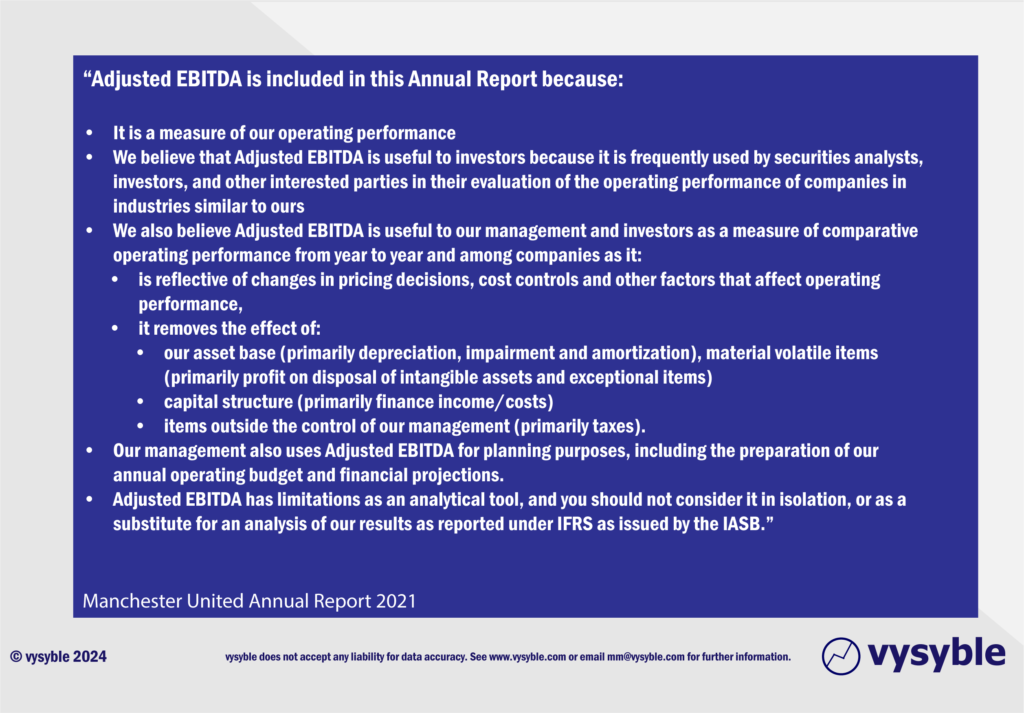

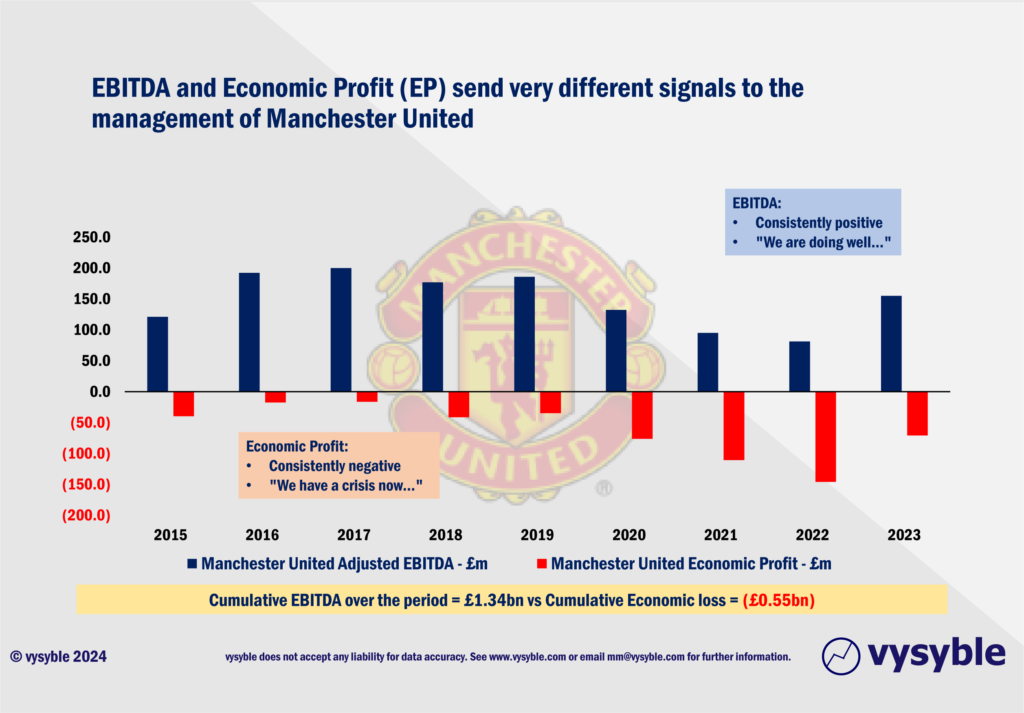

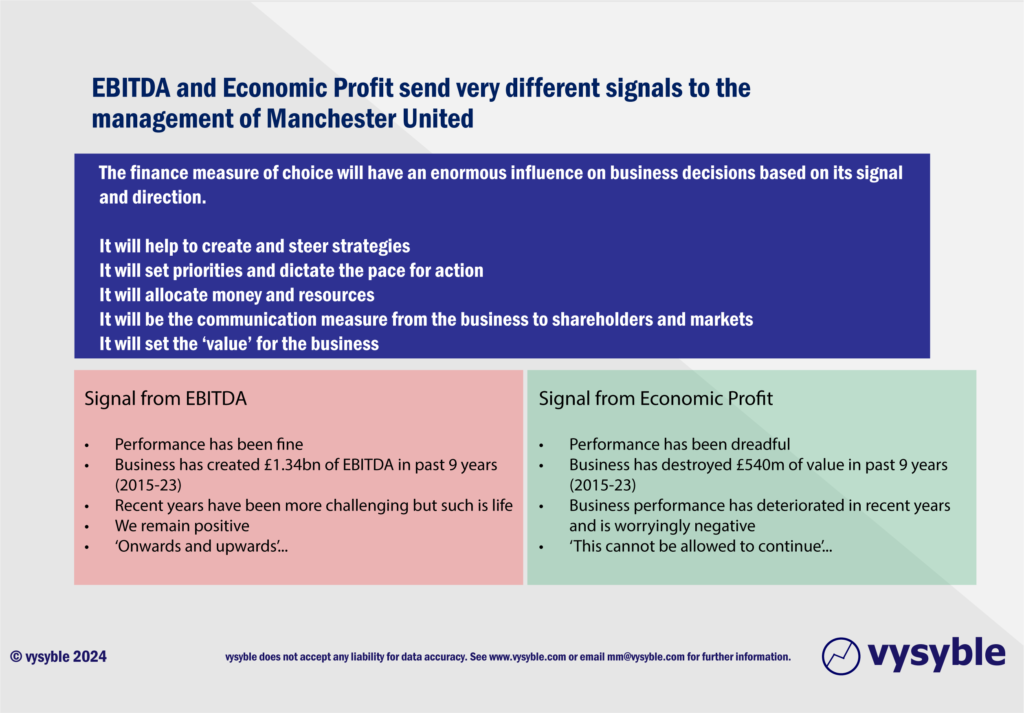

EBITDA was designed to help bankers to take a view on the ability of customers to make interest payments on debt from short-term income. It is now widely misused as the measure of choice regarding business performance in many industry sectors. The Board of Manchester United are, evidently, fans of this metric because it can and often does flatter underlying poor performance.

“It amazes me how widespread the use of EBITDA has become. People try to dress up financial statements with it.”

“We won’t buy into companies where someone’s talking about EBITDA. If you look at all companies and split them into companies that use EBITDA as a metric and those that don’t, I suspect you’ll find a lot more fraud in the former group.

Look at companies like Wal-Mart, GE and Microsoft — they’ll never use EBITDA in their annual report.”

Warren Buffett – Berkshire Hathaway 2003 Shareholder’s Meeting

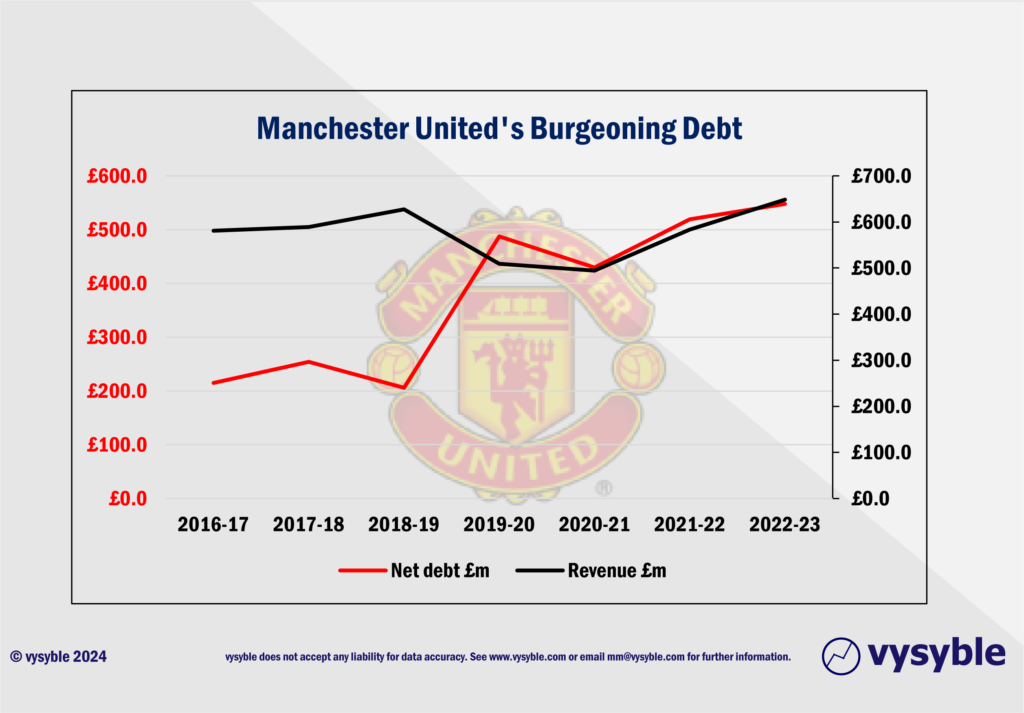

Consequently, as the economic profit signal is negative, Manchester United is struggling to generate internal funds to finance its activities. As a result, net debt has ballooned despite revenue growth which is often lauded by commentators (see graphic below).

In the above graphic , the right-hand axis measures the growth in revenue between 2017 and 2023. Despite an understandable contraction in 2021 due to the pandemic, the overall picture is one of revenue growth. However, net debt as shown on the left-hand axis is on a deeply troubling trajectory given that since June 2017 the level of net debt has risen by 109%.

Future Turmoil

Now that we have laid out the near-perilous state of Premier League club finances, the recent actions or inactions displayed by the club owners regarding the transfer of funds to the lower leagues can be put into context.

The key element to bear in mind is the rather odd dynamic in that the leading group of clubs, which are generally economic-loss achievers, subsidises a larger group of economic-loss achieving clubs who all want to be part of the leading group and will spend near-perilous amounts of money to achieve this and displace other clubs from the group despite the fact that being part of this leading group does not usually lead to instant riches, profit or value creation.

If, on the other hand, the Premier League clubs were successfully profitable on a regular basis then it would seem eminently reasonable to feed some of the money generated from commercial revenues at a collective level back into the lower leagues and beyond to preserve and grow the game in England for future generations.

Not only is the current dynamic out of kilter given the respective financial positions of both groups, but it also betrays the self-interest of certain owners and their disregard for the wider domestic game.

The Daily Mail has reported that 10 Premier League clubs refused to progress the subsidy proposal for the English Football League. They are Arsenal, Chelsea, Tottenham Hotspur, Liverpool, West Ham United, Aston Villa, Wolves, Nottingham Forest, Crystal Palace and AFC Bournemouth.

Six of the above clubs are either owned by US interests outright or have a shared interest (Aston Villa). Just two are majority owned by domestic interests (Tottenham Hotspur and West Ham United).

We have often highlighted the potential impact of US and foreign ownership in the Premier League, especially with the increasing prevalence of private equity-sourced acquisitions. A US-based private equity operative would very likely be aghast at being forced to subsidise competitive elements which could seriously devalue the initial investment. Thus, it is not difficult to see how the existing arrangements could (and appear to be doing so) unravel very quickly given the ownership profile of the current Premier League clubs and perhaps a lack of understanding by such foreign interests of the implied collective fraternity of the wider English game.

A further consideration is the Premier League’s administrative about-turn regarding the punishment for breaching the profit and sustainability limits. In a previous blog, we’ guestimated’ that a Premier League point is worth anything between £4-6.5m. With Everton’s fine now standing at 6 points, the club has effectively been docked between £24m-£39m, a sum which it can ill-afford given its debt exposure and trading position (see above).

From our perspective, this is a case of ‘too little, too late’ by the Premier League’s administration. We opened this blog by talking about pivotal points. The TV contract of 2016 is one of those points in time. The upwards step change in broadcast-related revenues enabled the Premier League clubs to achieve two successive years of collective economic profits following years of losses. At the same time, clubs in the EFL championship turbocharged their already reckless spending in order to obtain a slice of the apparent riches of the Premier League pie. Short-term gain for the Premier League clubs resulted in long-term pain elsewhere.

We went public with our analysis in 2017 and pointed out very clearly that there had to be reform of the operational governance of football to make the game financially sustainable as well as the fending off the impending prospect of a Super League if this did not materialise. The game’s administrators failed to act, losses have mounted, and would have done so even without Covid in our view, and here we are…

And whilst it could be argued that Covid is a very strong mitigating factor in football’s poor economic performance – Premier League clubs achieved economic losses of £1.38bn in 2019-20 and £1.09bn in 2020-21 – in the season prior to Covid hitting the world and in the last year of that abundantly rich 3-yr TV contract from 2016, Premier League clubs achieved a then-record economic loss of £599m from an equally record-busting revenue level.

So, who is who’s own worst enemy? The Premier League’s administration for being utterly blind to the effects of continuing (economic) losses? The club owners for spending beyond their means in the quest for glory? The fans for demanding even more?

There is no doubt that there have been many challenges for football in general. In shifting from a lax approach to one of rigorous intolerance only when a regulator is all but certain to appear from over the horizon smacks of last-minute panic. Sadly, the clubs remain in the position that we realised back in 2017 when we conducted our first analysis. They seek control over costs but are unable to do so because the framework of regulation is weak and allows for continual capital/equity injections which the accountants don’t cost for but we do. It is these very capital injections which fuels increased spending and so the spiral into bigger losses continues. Once factored in, we see the balance sheet and business performance damage earlier and in much more detail.

Additionally, the situation with Manchester City also deserves greater scrutiny. The Premier League argues that such a complex case regarding alleged transgressions of the financial rules and regulations takes a significant amount of time to put together. However, the casual observer may wish to add that if the rules were robust enough in the first place, then a more compact and perhaps effective set of charges could have been served at an earlier juncture. Even so, one elephant in the room is difficult to manage. A herd of 115 elephants is a challenge on a totally different level, one which will inevitably drag on and on to the detriment of all concerned.

The influx of foreign investor-led, capital return-driven funds and their operators into the ownership spectrum of English football should have served as a warning to the Premier League’s administration. With merger and acquisition activity off the table, football was being asked to deliver a return for these investors in one of two ways, either by operational or structural reform.

Given that the operational aspect would have been an easier option had the right regulatory regime been in place, we are now in a volatile period of structural reform. Project Big Picture and Super League was just the start of football’s structural upheaval. The division’s reticence to endorse an enhanced financial package for the English Football League is another reflection of the senior clubs looking to change existing practices and perhaps accelerate away from the financial demands of the wider domestic game. The disclosure of continuing discussions with the Super League version 2 promoters A22 is, sadly, no surprise to us. From an economic and value standpoint, nothing has changed since 2021 when version 1 came along.

Indeed, no longer are the offshoots of cricket clubs, church and works teams the sporting enterprises of old. The modern version is an investible entertainment platform with the potential of achieving global reach for private equity investors and ultra-high net worth benefactors who perhaps seek a heady mix of profile and returns but who must keep the show on the road with near-continuous capital injections and mounting losses. Football for all its glamour comes with a very high price.

This quest is not served by weak regulation, poor strategic vision and a limited understanding of the economics at play. The clubs do seek greater control over costs but also over their destiny. We argued that the demise of the Premier League was underway back in 2018. The latest series of events does nothing to dissuade us from our view. The detachment of the senior clubs from the domestic game continues with European competition firmly within their sights even though places are currently limited. Just look at the number of annual reports from Premier League clubs who state that European football is a primary competitive aim and have shaped their budgets to achieve it. Not all will be or have been successful. If they can achieve more control over competition structure and diminish the influence (and the percentage take of sponsorship revenues) of UEFA, then all the better for the individual club owners.

We have previously pointed out that if you put all the senior club owners in a room and asked them to come up with a new framework for football, it would be extremely unlikely that it would result in what we have today. Even so, successive UK governments have promoted the Premier League as an advertisement for the country, and from an entertainment and marketing perspective, it certainly is. A regulator would not be minded, nor allowed we think, to dilute this view. Unfortunately, marketing reach and value creation are not the same thing. Indeed, the corridors of power display a naïve but prevalent perspective in this regard. And it is this difference in perception that will exact a heavy price on the domestic game.

However, we can almost hear the cacophony of running footsteps in the Palace of Westminster as the Premier League lobbyists chase ministers and MPs to water down the forthcoming Football Bill as it lumbers through the presentation process. Indeed, it will be interesting to gauge the opinion of those MPs whose constituencies fall dead-centre in the stadia of the nation’s top 20 clubs. With a fracturing Premier League, the pressure on any incoming regulator to sort out the impending mess will be immense. Yet we doubt that a regulator be empowered to achieve this. Looking at other industries with a government-appointed oversight, the omens are not overwhelmingly encouraging.

Unfortunately, we can only see further turmoil as financial pressures continue to grow within the game. Left unrealised (and they probably will be, despite new and somewhat hurried initiatives), the miserable likelihood of a seasonal endeavour decided by lawyers on behalf of their investor/fund clients rather than the 22 players on the pitch looms larger by the day.

As a final observation, we are of the opinion that if the clubs were profitable in the first place, it is highly likely that none of this would have happened. The inability of the Premier League’s administration to proactively plan for a more sustainable future for itself and for football in general when conditions were favourable is a clear strategic failure. And we wonder what sort of (incorrect) advice those in positions of power were receiving from various consultants and auditors…

Pivotal moments indeed.

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter/X

5th January 2024 – Sheik, Ratcliffe and Joel – Manchester United’s investment saga and the challenges ahead.

18th November 2023 – House Rules – Everton’s financial behaviour incurs a 10-point deduction…

18th September 2023 – Way To Go! – US investor to buy Everton but where are the rest?

8th August 2023 – Does It Really Matter Anymore? – Football continues to lose money but the silence is deafening.

17th March 2023 – Half Empty – Half of the Premier League clubs have released their 2021-22 accounts. Not a read for the faint-hearted.

18th February 2023 – Blue Monday – Manchester City’s financial behaviour under the Premier League spotlight.

7th February 2023 – 25 Men Went to Mow – Chelsea’s US owners embark on talent spending spree.

24th November 2022 – Going Back Home – Not just Liverpool but Manchester United up for sale too.

9th November 2022 – The Leaving of Liverpool – Club owners appear to call it a day and mull sale of club.

30th September 2022 – Theatre of Breaking Dreams – Manchester United achieves its biggest annual economic loss.

4th August 2022 – Soccerball – Over-enthusiastic, over-subscribed and over here. The American invasion into English football is in full swing.

17th May 2022 – Money Heights – Valuation models fail to match the price paid to buy loss-making Chelsea.

25th April 2022 – Same but Different – UEFA’s proposed changes to Champions League qualification mirrors aspects of aborted Super League.

18th March 2022 – Let It Go – With a freeze on Russian assets, Chelsea hits the market following a record economic loss.

10th February 2022 – Underwater – Manchester United’s share price fails to defy gravity and sinks below its IPO level. Has the market got wise to the club’s poor economic performance?

1st December 2021 – Fantasy Football – The Fan-Led Review findings fall short of the necessary value-driven approach to regulatory reform.

23rd June 2021 – Road to Nowhere – Football stands at the crossroads ahead of the Fan-Led Review process. We examine the key questions that it must answer.

11th May 2021 – Prime Numbers – Football’s elite clubs seek a route to profit as fans yearn for sporting tradition. In between lies a gulf of mistrust and misapprehension.

26th April 2021 – A Bitter Pill – GSK’s new strategic direction fails to find riches in the middle of a pandemic when other pharma companies have prospered.

25th April 2021 – The Wrong Stuff – American-style football league won’t wash but the conditions that led to its launch are still present and are likely to get worse.

19th April 2021 – Super League Arrives – As we predicted, football’s elite breakaway emerges from the shadows.

30th March 2021 – $hooting B£ank$ – Arsenal’s commercial performance analysed.

22nd February 2021 – Measure for Measure – Take two financial measures, add pandemic and stir.

18th January 2021 – The Football Factory – If football was an industrial entity…

8th January 2021 – The Oil Majors – An Update – A shareholder return performance review of the 4 major oil companies in 2020.

10th December 2020 – Pump Up The Volume – ExxonMobil comes under fire from an agitated investor.

16th November 2020 – The Pain Game – Manchester United’s Q1 2021 financial release opens the lid on a Covid-19-affected financial can of worms.

11th November 2020 – A Tight Squeeze – Football’s Elephant in the Room leaving little space for financial relief.

29th October 2020 – Form and Function – Proposals-a-plenty for football’s structural reform.

13th October 2020 – Project Big Profit – Americans come bearing a proposal for football’s structural reform, just as we predicted in 2016.

8th October 2020 – Game Aid – Football is caught in the crossfire of indecision and financial necessity.

24th September 2020 – Crisis? What Crisis? – We look back 12 months at the demise of Thomas Cook and its relevance to more recent events.

11th September 2020 – Distance Learning – New rules and new values as Covid-19 challenges traditional mindsets and misconceptions.

19th August 2020 – Socked! Marks & Spencer’s Shrinking Value – Retail giant is fast becoming a shadow of its former self.

22nd May 2020 – You’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat – An assessment of the double financial whammy of potential relegation from the Premier League and Covid-19.

30th April 2020 – Home, Alone – Initial indicators from the wider economy point towards economic and financial downsizing in sport.

6th April 2020 – Board Games – Government, football clubs and players adopt separate ‘brace’ positions as Covid-19 crashes the sports economy.

27th March 2020 – Markets, Mayhem and Manchester United – A look at the questions posed by the share prices of publicly listed businesses.

15th March 2020 – When Saturday Goes – Football has come to a halt. We take stock of the game’s position and ponder its return.

10th March 2020 – Futureworld – The potential economic effects of the COVID-19 outbreak.

19th February 2020 – Lemon Law – How Financial Fair Play can give a misleading view of football club finances.

8th February 2020 – Hammered – Our financial perspective on some of the clubs involved in the Premier League relegation battle.

12th December 2019 – The Cost of Chasing Gold– In collaboration with the BBC, we look at the high price being paid by clubs to gain promotion into the Premier League.

7th November 2019 – Where to Next for M&S? – November 2019 results suggests the retailer is losing its way

10th October 2019 – Red Mist – Manchester United’s 2019 FY numbers and the stagnation of England’s biggest revenue-earning club.

7th September 2019 – Not Just A Loss But… – A detailed look at the decline in Marks & Spencer’s fortunes.

29th August 2019 – Telling It Like It Is… – What really happened when we talked to the English Football League.

5th July 2019 – Chopping Board – Knives out for former Tesco chief.

25th May 2019 –Repeat Prescription – Few believed us the first time around regarding football’s financial plight…

19th March 2019 – Stuff and ‘Nonsense’– Why the Economic Profit metric is the most transparent measure of business performance.

13th March 2019 – Financial Fair Play – Guilty as Charged? – Our thoughts on FFP schemes and their key weakness.

18th December 2018 – Long Division – The Post-Ferguson years at Old Trafford have come at the expense of declining economic and on-pitch performance.

20th November 2018 – The Relegation Game – Tales of woe and economic performance at the wrong end of the Premier League table.

9th October 2018 – A Different View – Why fans ought to be acutely aware of football’s financial dynamics.

17th August 2018 – The End of the Beginning – La Liga heads west to conquer new worlds.

9th August 2018 – Reaching for Sky – the sequel – Latest offer price for satellite TV company is good for shareholders, less so for prospective owners.

8th August 2018 – American Dreams – English Premier League economic dynamics and American money – is a Euro Super League the next step?

3rd August 2018 – Mall Administration – Retail Property Co. bonus payouts at odds with increasing shareholder value.

20th April 2018 – Goonernomics Part Deux – The departure of Arsene Wenger…

18th April 2018 – The Price of Everything – Tesco’s latest numbers offer little in value.

12th April 2018 – Say What? – WPP’s very mixed message.

14th February 2018 – In Case of Emergency – Premier League’s UK TV rights auction comes up short.

7th February 2018 – Lost in Transmission – Top Premier League clubs look beyond domestic TV rights.

4th December 2017 – A Billion here, a Billion there… – The Premier League reaches a major milestone, quietly…

25th November 2017 – Getting out of Toon. – Is Mike Ashley pitching the sale price of Newcastle United at the right level?

16th October 2017 – Goonernomics. How the ‘Bank of England’ club falls short of its North London neighbour.

25th September 2017 – Highlights. More record-breaking numbers from the biggest football club in the land, but no economic profit…

23rd September 2017 – Football’s Economic Back Pass. A guest blog for the Soccernomics website.

12th September 2017 – Crystal Balls-up. Changing strategic direction is not a good idea when you haven’t looked at the economics.

27th July 2017 – Football’s Summer of Money and the £65 pint of beer. The sport that just can’t spend enough.

11th July 2017 – Football Special. Observations following the launch of ‘We’re So Rich…’

9th May 2017 – Illuminating, non? Political energy lacks vision and power.

2nd March 2017 – Claudio’s Burden. The price of failure outweighs the price of success.

12th January 2017 – Shopping for Godot. A never-ending quest for value in Retail.

27th December 2016 – Reaching for Sky. Is Rupert Murdoch’s £10.75 per share a fair price?

6th December 2016 – Auld Lang Syne. A reminder from history of the damage that poor financial planning can cause.

1st December 2016 – Fork Handles? Four Candles? Tesco’s blurred strategic vision.

27th November 2016 – Football’s Instant Replay. Financial warning signals for the top English Premier League clubs