27th March 2020

Amidst the butchery that has been applied to the share price of virtually every listed company on the planet, one single comment regarding the irrelevance of Manchester United’s share price to the overall commercial fitness of the club attracted our attention.

“These are shares already owned by random shareholders, by hedge funds and private individuals, so it has no impact on Manchester United until the club wants to raise more money”

Here we lay out the strategic and business performance questions that a share price always asks of every publicly-listed business including Manchester United.

Introduction

The MDs and CEOs of publicly-owned businesses have always faced a massive and daunting challenge: how can they build – or in some cases rebuild – the value of their businesses? Their success or failure in meeting this challenge dictates how long they remain employed and the quantum or extent of their remuneration.

The current crisis on the capital markets, arguably triggered by COVID-19 but almost certainly a bursting of a bubble fostered by over 10 years of extremely cheap money, has nonetheless raised questions about what is meant by “value?” Some have questioned the very nature of globalisation and indeed capitalism itself.

For Manchester United, whilst things seemed to be improving on the pitch before the virus-induced suspension of play, it has undoubtedly been a challenging time for shareholders. The club’s New York Stock Exchange listed share price has fallen from $19.93 at the end of 2019 to around $13.40 on March 20th 2020 – a fall of some $6.53 or 32.7%.

All told, such a large fall has removed $800m+ from the value of club– at $13.40 the club’s market capitalisation is $2.2bn. As is so often the case in business matters, particularly at a time like this, there tends to be a lot of confusion and precious little wisdom.

However, we think the following questions are relevant:

- What are the different concepts to help us think about value?

- What are some of the common but harmful myths that drive a misunderstanding of what drives value on the capital markets?

- What is the metric that managers can adopt which over time will act as the best surrogate for capital market behaviour?

- In light of the above, how has Manchester United performed and what might be the questions that we might ask to interrogate both the strategy and management track record of the executive team?

- What are the different concepts to help us think about value?

We think there are four potential perspectives relating to value:

a. Stakeholder Value – “The business has duties to a range of Stakeholder constituencies.”

Such a perspective, often associated with a Continental Europe strategy orientation, essentially calls on companies to embrace a broader constituency of stakeholders beyond its shareholders. Indeed, for many companies across the globe with a long-term goal of value creation, we find it beyond argument that such an objective can be achieved without satisfied customers, suppliers and happy employees.

However, problems can arise when a company’s interests and those of its stakeholders are not easily aligned or complementary. How does a management team with limited resources manage or reconcile employee remuneration with say its commitment to the environment or to healthy supplier relationships?

Advocates of the ‘stakeholder value’ approach contend that companies can maximise value for shareholders and stakeholders at the same time without the need for trade-offs. Indeed, John Mackey, founder and co-CEO of Whole Foods Market makes such an assertion in his co-authored book “Conscious Capitalism.” (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing – 2013).

Strategic decisions often require a plethora of trade-offs between groups frequently in conflict with one another and in the absence of a coherent principled ‘basket’ of guidelines. The prioritisation of long-term value creation is our go-to ‘governing objective’.

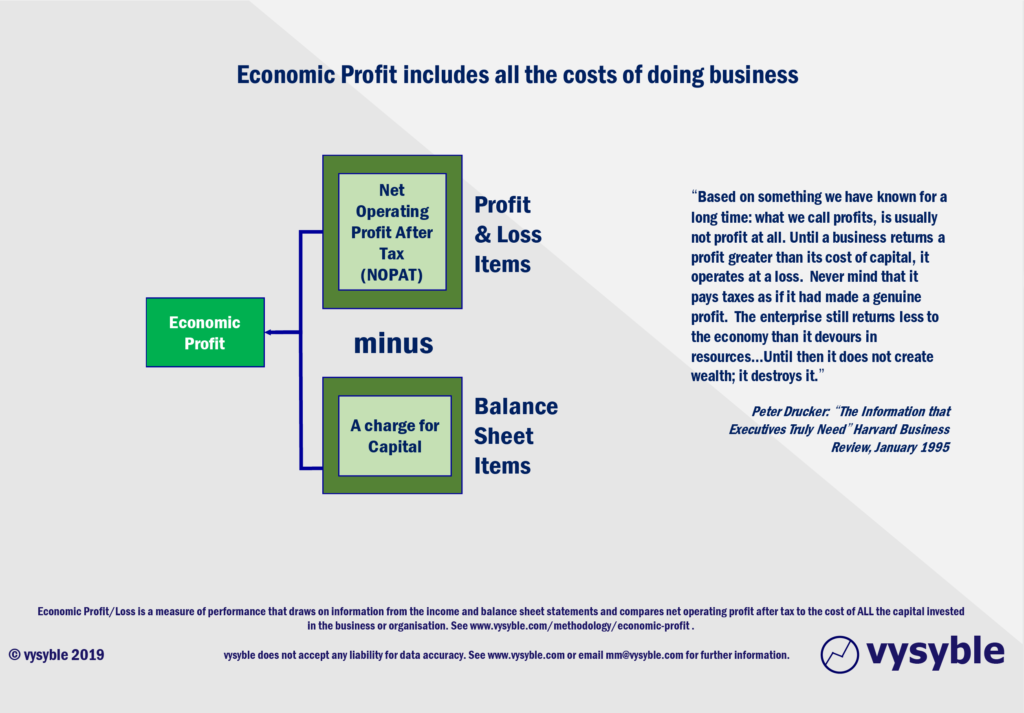

b. Fundamental Financial Value – “The business is worth its future cash flows or, equivalently, its future Economic Profits (EP).”

By this, we mean the returns made by the business relative to the capital used by the business to deliver those returns. This is essentially in line with Marshall’s definition of value creation:

“Value is created by investing capital and generating a return greater than the cost of that capital” (Principles of Economics – 1890)

It is now widely accepted that the appropriate approach to valuing a business is to forecast cash flows to infinity and then to discount that stream back to the present day by applying a discount rate. This is called the DCF approach.

Commonly used DCF methodologies include:

- Enterprise Free Cash Flow: estimate free cash flow then discount using the Weighted Average Costs of Capital (WACC)

- Equity Cash Flows: estimate cash flows to equity then discount using the calculated cost of equity

- Economic Profit (Fundamental Financial Value): estimate future EP then discount at the cost of equity

Note: Fundamental Financial Value is sometimes called or referred to as “Intrinsic Value”

c. Shareholder Value – “The business is worth what investors say it is worth.”

Share prices are affected by many forces, including investors views on:

- The capability and reliability of the senior executives

- The health or otherwise of a particular sector or market

- Broader economic, political, and societal dynamics

Many of these forces can be influenced but cannot be controlled by management.

So, when viewed through this lens, Stock Market Values and Fundamental Financial Values are often different. Although over time they do tend to converge.

d. Relative Value – “The business is worth what other similar businesses have been sold for.”

Bankers use this approach when they are trying to buy or sell businesses. They call it Relative Value or “what has been paid for similar businesses?”

Bankers also usually use an accounting metric called EBITDA (“Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortisation”) when they benchmark businesses when using a Relative Value approach. We recommend as further reading some of the more recent and less than endearing quotes in the media regarding EBITDA from Warren Buffet’s business partner, Charlie Munger.

Managing for value creation over time has no use for the EBITDA metric. Sadly, there are academics and consultants who continue to peddle this financial snake oil to anyone who will listen.

In our consulting work, we very much favour the Fundamental Financial Value approach.

2. What are some of the common but harmful myths which drive misunderstanding of what drives value on the capital markets?

We will focus on two, namely accounting earnings and the belief that all revenue is value creating.

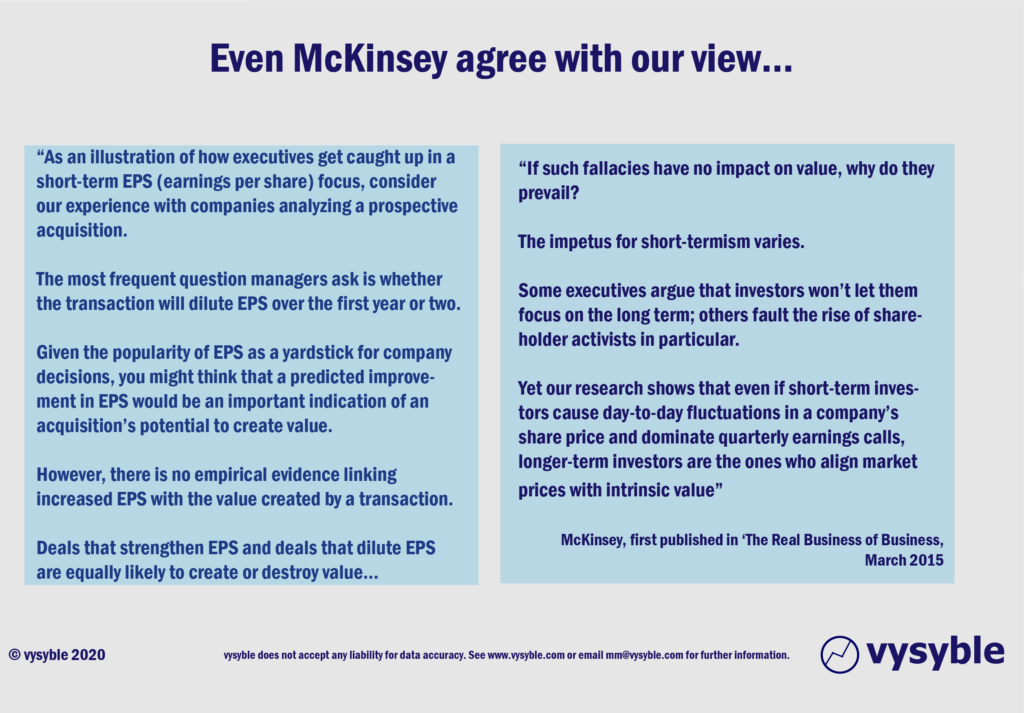

Accounting earnings and growth thereof is a driver of value creation.

This is a belief so deeply ingrained within many management teams that at times we wonder whether it was originally part of the religious education curriculum. Despite overwhelming evidence including testimony to the Federal Reserve that the use of accounting earnings is not a reliable indicator of either value creation or indeed superior decision-making, many CEOs, business journalists and university lecturers continue to believe and propagate this particular fallacy.

The above graphic reveals that Enron’s strategy from 1994-2000 was destroying value (left-hand chart) and yet the earnings per share (because it excludes all of the costs of capital) trend was increasingly positive (right-hand chart). In this case ‘the smartest guys in the room’ were not those extolling the virtues of Enron’s focus on earnings per share, unlike the featured quote from Enron’s annual report…

The issue or problem is that accounting earnings is an incomplete measure of performance. More particularly:

- It fails to account for both the amount and cost of ALL the capital needed to run and grow the business

- It is not a measure of cash flow. Earnings last year or next year tells us very little indeed about the cash flows that the business will deliver in the future

- It contains nothing about how risky earnings are, either now or in the future

- It says nothing about the need for or role of intangible assets which are an increasingly important ingredient in many companies

- It can be easily manipulated or distorted using perfectly legal accounting conventions

Usually we find accounting earnings in the role of the principal metric guiding management teams in their strategic discussions and deliberations. In our view, it undoubtedly results in organisations allocating further capital to lines of business that are destroying value.

A key dynamic is that the analysts of the City and Wall Street continue to focus on earnings, earnings growth and forecasts thereof. Such a focus gives CEOs and other commentators the overwhelming impression that meeting analyst expectations is a pre-requisite for the company’s equities to perform well on the wider capital markets. In addition, the frequent interaction between CEOs and analysts only reinforces the apparent importance of accounting earnings and its growth.

However the current dynamic confuses inputs with outputs and also presumes that ‘analysts’ are one and the same with the wider capital market. This is just not the case.

On reflection, it might help CEOs if they thought of capital market analysts as similar to film critics; if you perform only to meet the expectations of analysts then the commercial success of your film is far from certain: but, if your performance consistently makes audiences (or investors) happy, you can ignore the critics! One immediately thinks of “The Shawshank Redemption,” and “Bohemian Rhapsody” – two enormously successful films at the box-office which were universally panned by the analysts, sorry, film critics.

Here is the perspective of the Sage of Omaha, one Warren Buffett;

“Wall Street is the only place that people ride to work in a Rolls Royce to get advice from those who take the subway”

“We’ve long felt that the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good. Even now, Charlie and I continue to believe that short-term market forecasts are poison and should be kept locked up in a safe place, away from children and also from grown-ups who behave in the market like children.”

The belief that all revenue is a driver of value creation is sadly misplaced.

“The curse of all curses is the revenue line,”

Roberto Goizueta – CEO of Coca-Cola (1982-97) with an incredible record of driving returns for shareholders

“Growth is simply a component – usually a plus, sometimes a minus – in the value equation.”

Warren Buffet – an extract from the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report – 2000

The above are regularly and deeply held within management thinking. Surely, all revenue must be good and must be adding to the so-called “bottom line?”

Well, unfortunately, life is not as simple as that. Not all parts of the market create value and yet executives continue to believe that all revenue growth is good. Sadly, it is rare for executive teams to have sufficient visibility of value creation by product, customer segment, time of day, geography, asset class and so on.

Consequently, their understanding of the economic engine room of the business is at best misguided and is often wrong. It is true that many executive teams try to segment their markets by product and by consumer type, usually to gain a better understanding the needs of their customer.

However, few executive teams take the next step and try to establish the value created by segment either currently or in the future. As a result, they observe business “profitability” through an aggregate accounting perspective. When viewing through this lens all revenues looks good, all costs look bad and opportunities to manage the overall business mix are just not seen, never-mind acted upon. In this context, you can’t manage what you can’t see…

Viewed through an aggregate perspective, there is a natural and understandable desire to lean towards revenue leadership. Of course, underpinning all this is an in-going belief that significant competitive advantages accrue as night follows day from a “dominant revenue position”. Economies of scale, marketing and distribution benefits and being the market leader must help in keeping the product front of mind with the customer. Surely, these advantages must lead to a superior fundamental financial performance?

Unfortunately, the answer is ‘not necessarily’. A “Charge of the Light Brigade” pursuit of a market share strategy makes the same assumption that we began this section with in that all parts of the market are equally attractive and value creating.

It is simply not true.

“There is a propensity to grow regardless of the consequences to the shareholder. It is present in all companies, even the best managed. It is an extremely tenacious force that works incessantly against achieving superior shareholder returns. Not all growth is good. Your focus must be on the things that increase shareholder value”

Brian Pitman – Chairman and CEO of Lloyds Bank with an enviable track record of generating returns for shareholders.

Of course, there are a number of other myths which affect modern management thinking – notably the belief that capital markets are only interested in short-term performance and that share buy-backs are always create value.

However, the reason why we highlight the foolishness of earnings as a surrogate for value creation and the belief that revenue in all cases is value creating is that the football finance commentary as we see it is particularly affected by these myths.

3. What is the metric that managers can adopt which, overtime, will act as the best surrogate for capital market behaviour?

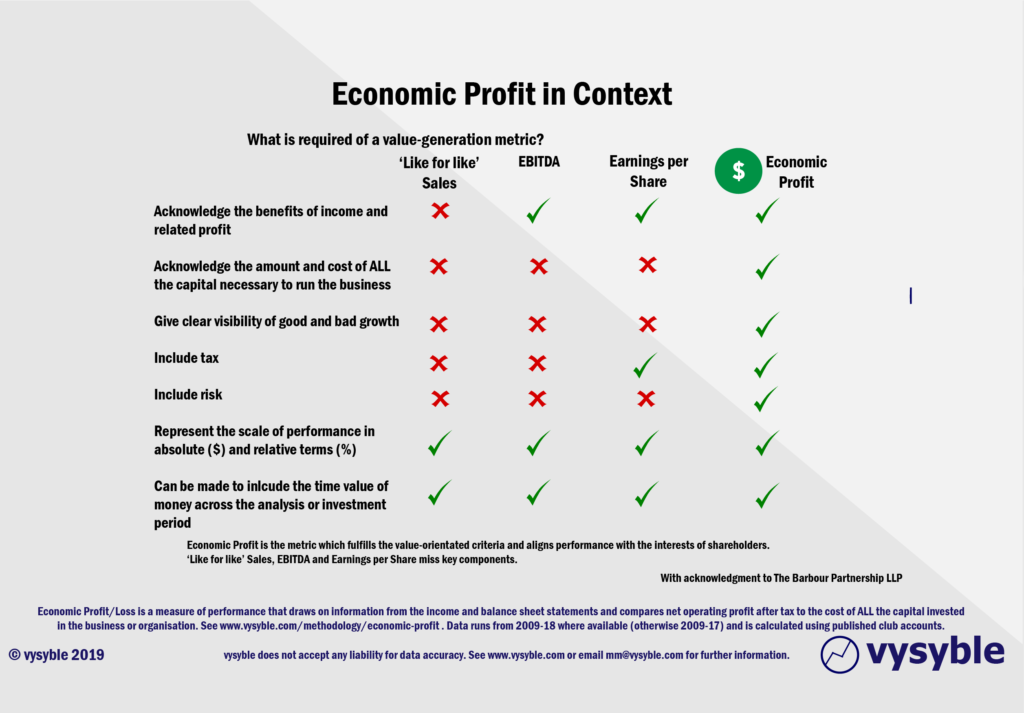

What do we want a metric focused on value creation to do? Set out below are the criteria underpinning a value-to-shareholders metric.

It is for the reasons outlined in the above graphic and also Marshall’s definition of value creation that we take an economic view of companies rather than the typical accounting perspective.

Our viewpoint enables us to present our clients with new and very different insights into the real drivers of value for their own businesses, their competitors, and their industry overall.

“Creating economic profit is the single most important driver of the stock price of the Coca-Cola company”

Roberto Goizueta, former Chairman and CEO of the Coca-Cola

“The EVA (i.e. Economic Profit) approach to equity analysis has become increasingly popular because it more accurately reflects economic reality (as opposed to accounting reality) when compared with many traditional valuation measures such as earnings per share (EPS), return on equity (ROE), and free cash flow; those accounting-based measures can be distorted by accounting practices. They also include the cost of debt and exclude the cost of equity…..Focusing on the variables that drive the underlying economics of the business, rather than on accounting-based benchmarks, should result in improved management, financial analysis, and ultimately, enhanced shareholder value”

Goldman Sachs

“Internal management misconceptions, not external competition, are the most significant impediments to improving shareholder value.”

Jim Kilts, former Chairman and CEO of Gillette, President and Chief Executive of Nabisco and President of Kraft

4. In light of the above, how has Manchester United performed and what questions might we ask to interrogate both the strategy and management track record of the executive team?

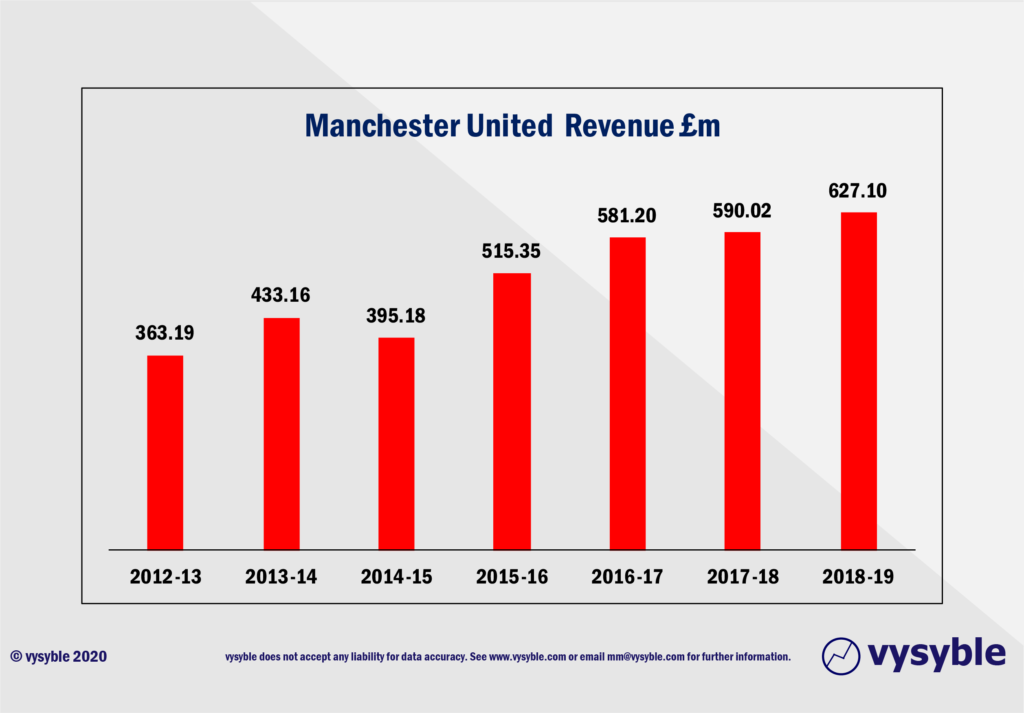

Manchester United’s revenue is impressive. Not many companies are in a position to achieve a 72% increase in revenue over a six-year period.

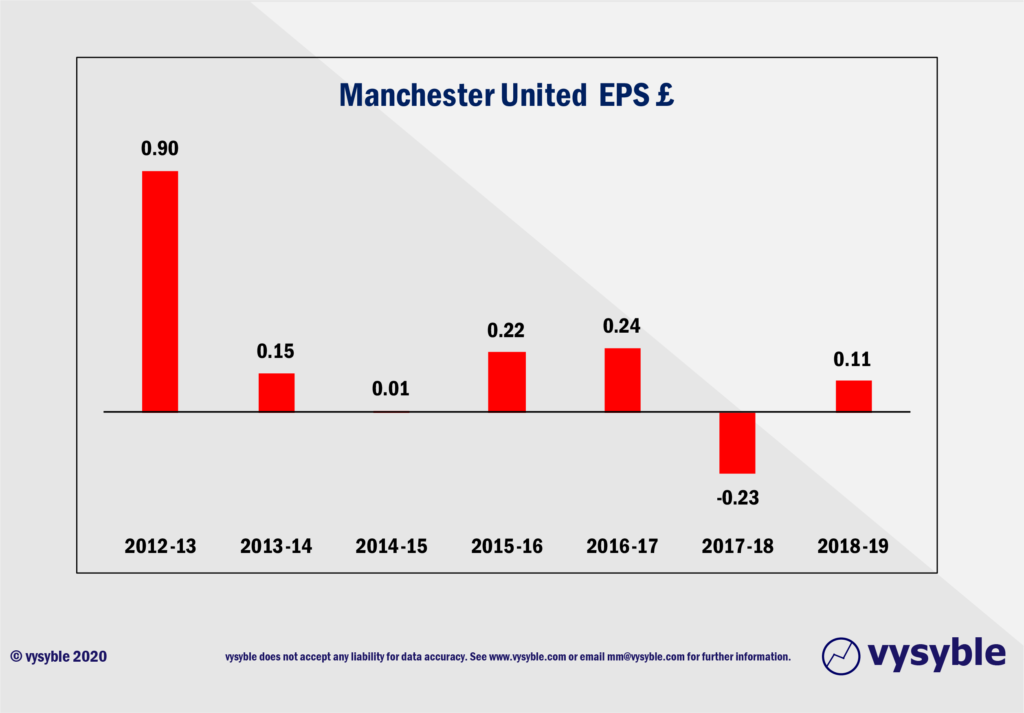

With good revenue growth and an earnings per share profile that is predominantly positive, the capital markets would view the share in a positive light, yes?

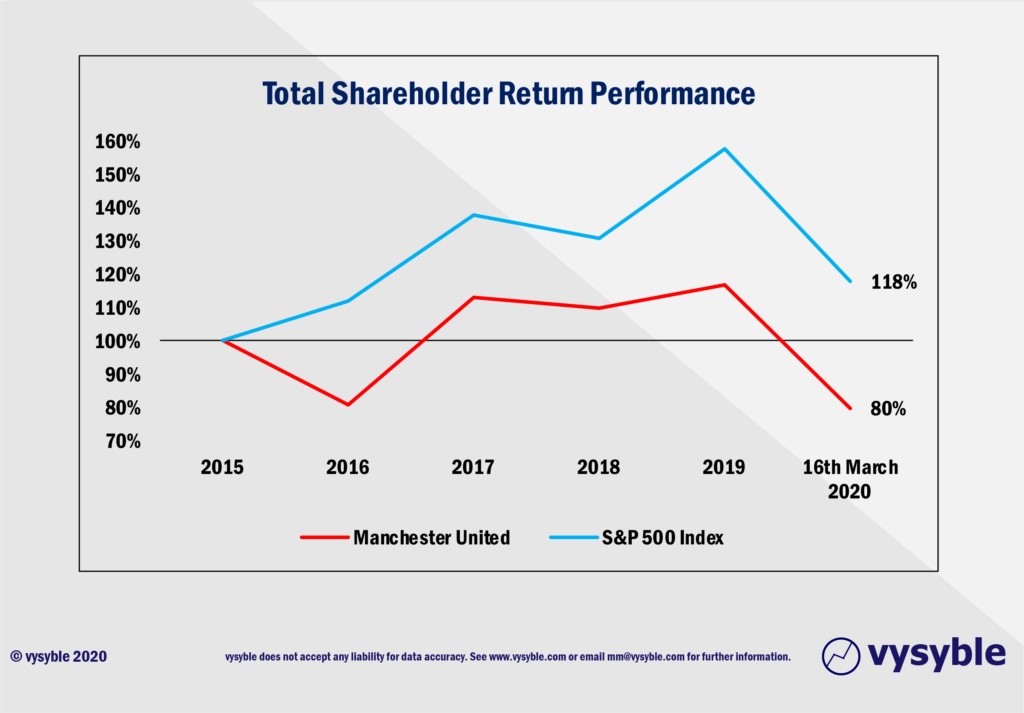

Actually, no. Manchester United’s share price has consistently lagged behind the S&P 500 since December 2015. Investors would have achieved better returns by putting their money into a S&P 500 tracker fund. Indeed, $1 invested in Manchester United at the end of Dec 2015 would be worth 79 cents by 16th March 2020.

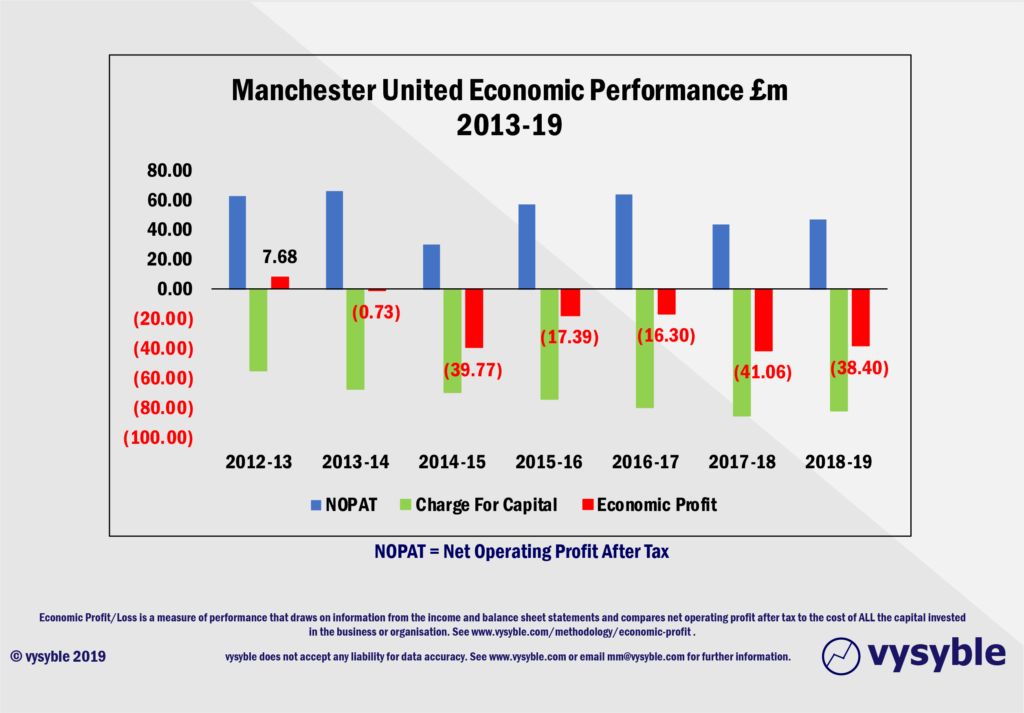

The fall in the Manchester United’s Total Shareholder Return (TSR) trend is driven by the decline in Economic Profit achieved by the club’s current set of objectives and strategy. Set out below is the economic performance of Manchester United since 2013.

Despite the hugely impressive growth in revenue, the club has underperformed from an economic profit perspective and remains firmly in the “share to admire but not to have within one’s pension fund” category.

As the economic performance of the club is generally poor, this will inform future expectations and hence share price perceptions.

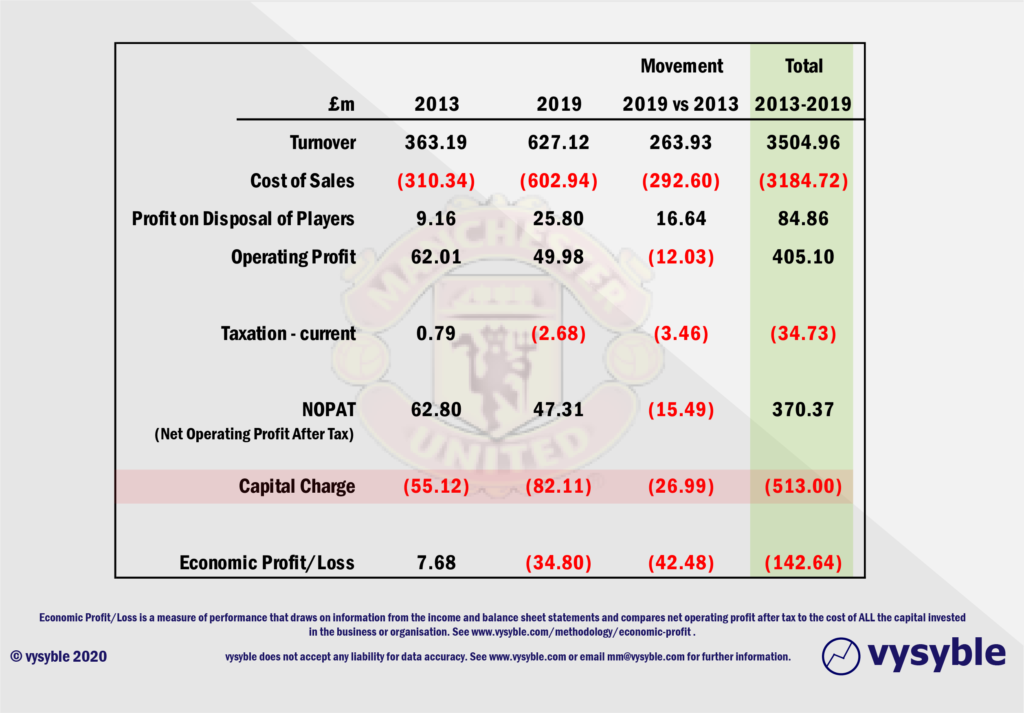

The movement between 2013 and 2019 helps to illustrate the underlying trend.

2013 Revenue = £363.2m.

2013 Costs, including tax = £309.6m.

When the transfer surplus on players is included, and the charge for capital is deducted, the 2013 economic profit = £7.7m. This is the last time that the club posted an economic surplus.

By 2019, Revenue had risen by £263.9m, reaching £627.1m.

Costs, again including tax, reached £605.6m.

When the transfer surplus and the charge for capital are accounted for, the economic loss = £34.8m.

Therefore, between 2013 and 2019, revenue had risen by £263.9m but the costs of generating that revenue have risen by a bigger value ie £296.1m.

In other words, the cost base has risen by £32.2m more than the revenue increase.

Over the period the club has produced economic losses totalling £142.6m. That is, the strategies adopted by Manchester United’s executive team have taken £142.6m of shareholders’ funds and given it to other stakeholders which are likely to be the players and their agents in the form of staff costs and associated fees.

So the next time when you hear commentators talking about revenue growth as a surrogate for value creation, they are explicitly revealing their naivety.

This leads us to our next section. How might we think about how well the club is being managed? With this in mind, there are two key questions to be addressed:

- Has Manchester United been a good investment for shareholders?

More particularly how has the club performed for shareholders; both in absolute terms and in relation to a peer set (which in this case is limited)? Here we normally look at the TSR performance in absolute terms; compared to other companies in a peer set; and with chose indices.

2. How well has Manchester United been managed by the CEO and his team?

Is the club managed in a way that should drive superior returns for shareholders?

We start by applying six core tests:

- The Fundamental Value Test

- Is the CEO delivering the type and quantum of performance that should drive the share price?

- The Governing Objective Test

- Is the CEO setting the right objectives for the business?

- The Financial Metrics Test

- Is the CEO driving the business to use financial measures that are aligned well with value?

- The Value-based Strategy Test

- Does the CEO appear to have a strategy for the business which takes account of the economic, strategic, and competitive realities it faces?

- The Organisation Test

- Has the CEO structured the business and imposed ways of working that seem to be well aligned with value?

- The Management Rewards Test

- Are management rewards and incentives for the CEO and other senior managers aligned with creating value?

- Has Manchester United been a good investment for shareholders?

Previously we displayed a graphic revealing the inferior TSR of Manchester United against the S&P 500 index over the period Dec 2015 to March 2020.

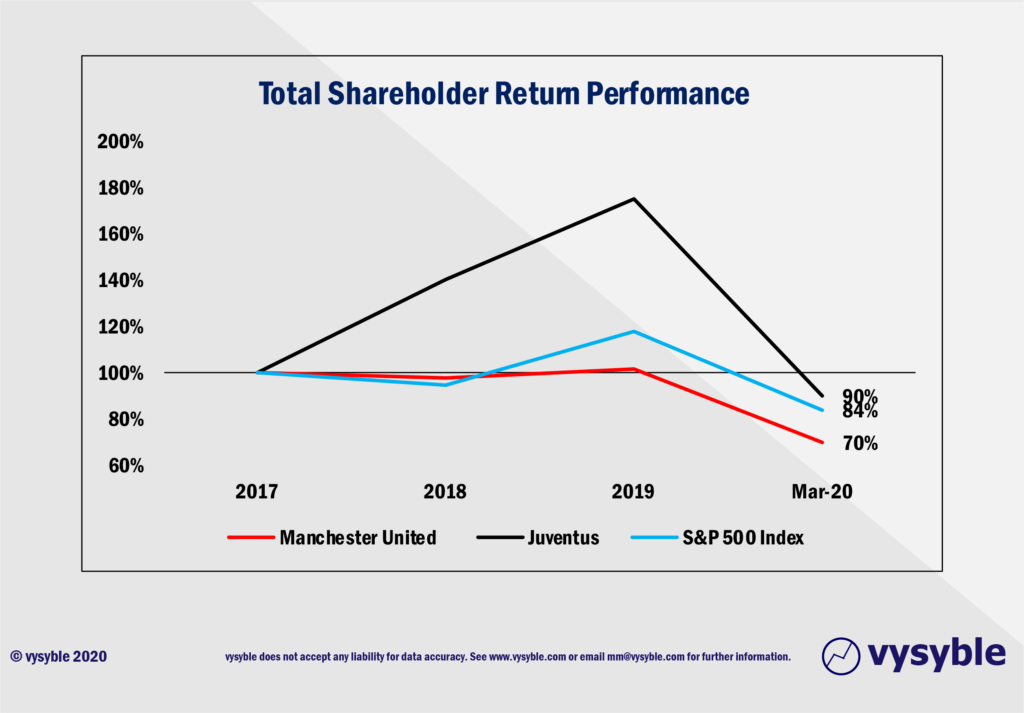

However, to ensure that the start date of the analysis period is not influencing the subsequent conclusions, we have run the numbers at this point with a start date of Dec 2017 (re-basing all elements back to 100) through to March 2020. To add a peer set dimension, we have also included the TSR of Juventus, another publicly-quoted football club.

Once again, we see Manchester United lagging behind both the S&P 500 Index and Juventus.

For example, £1 invested in Juventus in Dec 2017 was worth 92p by March 2020. A similar calculation for Manchester United saw a £1 investment dropping to 69.5p.

Therefore, taking an evidence-based perspective as seen above, we conclude that the club has not been such a good investment for shareholders.

2. How well has Manchester United been managed by the CEO and his team?

The Fundamental Value Test – Is the CEO delivering the type and quantum of performance that should drive the share price?

In our 7 years of analysis (2013-19), the club has covered all of the costs of doing business only once (2013) and has posted economic losses to a total of £142.6m. Therefore, the answer the question must be a negative one.

The club has not produced the fundamental performance required to drive the share price. In fact, the fundamental performance of Manchester United is probably dampening expectations of future performance.

The Governing Objective Test – Is the CEO setting the right objectives for the business?

Here is an extract from Form 2019 20-F which is submitted by the club to the US Securities and Exchange Commission as part of its regulatory obligations to the New York Stock Exchange:

“The success of our business depends on the value and strength of our brand and reputation. Our brand and reputation are also integral to the implementation of our strategies for expanding our follower base, sponsors and commercial partners. To be successful in the future we believe we must preserve, grow and leverage the value of our brand across all of our revenue streams.”

Nobody is denying that the Manchester United brand is important. The point here is that the statement inclines one to the view that securing additional revenue is the governing objective and is the principal lens through which alternative strategies are ranked and selected.

The Financial Metrics Test – Is the CEO driving the business to use financial measures that are aligned well with value?

No. The CEO appears to be using EBITDA and Revenue, neither of which are well aligned with driving value for shareholders. The language used in company reports and statements is a very good indicator of the mindset and we have yet to see evidence of value-based language or terminology in Manchester United’s official financial releases.

Strategy so often fails because the Directors fail to see the true economic position of the business and as a consequence, they run with a strategy fundamentally misaligned with driving value.

The Value-based Strategy Test – Does the CEO appear to have a strategy for the business which takes account of the economic, strategic, and competitive realities it faces?

Also within the club’s Form 2019 20-F submission, there is a good explanation of the operating environment and in particular the club’s reliance on broadcast revenues which are in-turn driven by on-pitch performance. There is also a recognition that these revenues could fall due to a change in the broadcast contract(s).

We have no internal insight into the strategic processes within the business or club. Generally, we would argue that poor fundamental financial performance over time is a result of inferior strategic decision-making.

Indeed, the TSR and the fundamental financial performance cannot be described as “good.”

Nevertheless, we do think that the broad operational and strategic themes are probably correct.

A full value-based audit would bring the discipline of the stock market inside the business and reveal the areas where the club was creating and destroying value. In turn, this would produce new insights and help the senior management team to focus on prioritising the creation of value as opposed to an EBITDA -driven direction.

The Organisation Test – Has the CEO structured the business and imposed ways of working that seem to be well aligned with value?

Given that we are not ‘inside’ the business, we do not know enough to comment except that the given evidence points to poor value outputs and therefore there are probably blockages to value creation in structure, roles and responsibilities etc.

The Management Rewards Test – Are management rewards and incentives for the CEO and other senior managers aligned with creating value?

The statements published by Manchester United (Form 20-F) relating to executive compensation reflect a “belt and braces” approach. It is not immediately clear what the criteria driving a share award is to a given Director but experience would suggest it is determined by accounting rather than economic metrics. Consequently, the relationship between executive remuneration and value creation is perhaps more result of chance than anything initiated or fostered by the reward process.

Conclusion

Nobody is suggesting that even after the recent $800m+ fall in the market capitalisation that Manchester United is going to go under. The effects of the recent collapse in the share price are unlikely in the short-term to have any bearing on the immediate on-pitch performance once proceedings resume.

However, let us not confuse cause and effect. Over an extended period, the shareholder return performance of Manchester United is less than impressive.

Furthermore, the fundamental financial performance as exhibited by the club’s economic track record is troubling in a Premier League where most clubs are regularly posting economic losses outside of the Big 6 clubs. Our central point is that Manchester United has NOT found the value-maximising way forward or strategy for its shareholders and, more probably, for a range of other stakeholders too.

Strategic development, whether within the world of football or more generally across the world of commerce, is often hampered by a number of strategic shibboleths including the earnings myth which we examined earlier. Growing earnings and growing economic profits are related but they are certainly not the same thing and require quite different mindsets.

There are those who reject the economic approach to examining football’s financial and strategic performance with the argument that football clubs are not designed to make a profit and that they have a wider responsibility to the communities in which they are located. It is interesting that when pressed, that these objectors are unable to specify what is or would be an acceptable loss for the particular club that they follow.

In fact, we agree that the football clubs have a wider social function with consequent obligations to their communities. This is something that many of the clubs, including Manchester United, take very seriously and they often give their time and resource without the fuss that one often sees when something goes wrong. Our point is that the clubs can only fulfil their wider obligations if they remain solvent and the best way to facilitate that given all the available evidence is to adopt the economic profit metric as the measure of choice where ALL the costs of conducting business are evident.

This more demanding metric offers greater insights on the performance of the club in all of its guises and therefore the CEO and his team are more likely to see the club’s true economic situation.

Peter Kontes, in his outstanding book “The CEO, Strategy and Shareholder Value” asks the following question;

“Are there great CEOs who do not subscribe to economic profit growth or who stress other financial objectives? Absolutely. But there are no great CEOs whose companies fail to produce superior economic profit growth during their tenure, whether or not they assert that objective.”

This is a time of immense stress around the world but it seems to us that understanding the economic engine room of the organisation is now more important than ever.

And as for the finance expert who prompted this exercise with that comment, well….

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter