6th April 2020

Over the past week or so, a number of Premier League football clubs have elected to furlough some of their non-playing staff. This has been met with a degree of surprise, consternation and in some cases outrage with a public perception that football clubs are, in the main, profit-generating enterprises. The majority of players continue to be paid at full contracted rates.

At the weekend, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care joined the debate:

“Given the sacrifices that many people are making, including some of my colleagues in the NHS who have made the ultimate sacrifice…I think the first thing that Premier League footballers can do is make a contribution, take a pay cut and play their part”

In an interview on the Andrew Marr show, Gary Lineker questioned why footballers should be singled out. In The Guardian, Barbara Ellen’s observations published on 6th April 2020 are as follows:

“However, it was still unfair to frame this as footballers needing to be morally shamed into action because players don’t control how wages are paid. Such framing pitted “ordinary” people against not just football – in terms of big business – but individual players.”

Undoubtedly there are a number of points made from both sides of the debate but without the correct numbers there is a very clear danger that everybody is ‘dancing around the edges of the dancefloor’.

What are the drivers of this current foment?

The football industry like many other industries usually reports business performance in the form of annual reports. The most quoted numbers tend to be a combination of revenue and pre-tax profit.

We prefer to use the Economic Profit metric which is defined as:

Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT) less a charge for ALL the capital used by the business.

What does ‘ALL the capital’ actually mean?

It is the cost (interest) of every loan utilised by the business to maintain trading but it also and very importantly includes a charge for the capital invested into the business by shareholders/owner in the form of additional shares ie equity.

The charge for equity capital is not included in the accounts and accompanying reports and is not recognised as a chargeable item by the accountancy profession. The Economic Profit number also includes tax. Therefore, a pre-tax number is not an accurate view of the overall economic health of a business.

For example, the owner of Blog Athletic has already invested £100m in his/her club. This means that the economic profit calculation attributes a charge of £7.5m (7.5% charge which we apply as the Weighted Average Cost of Capital – see Economic Profit) to the overall business costs for this equity. If the owner invests another £10m to bring the invested total up to £110m, the overall charge to the business increases proportionally ie £110m x 7.5%.

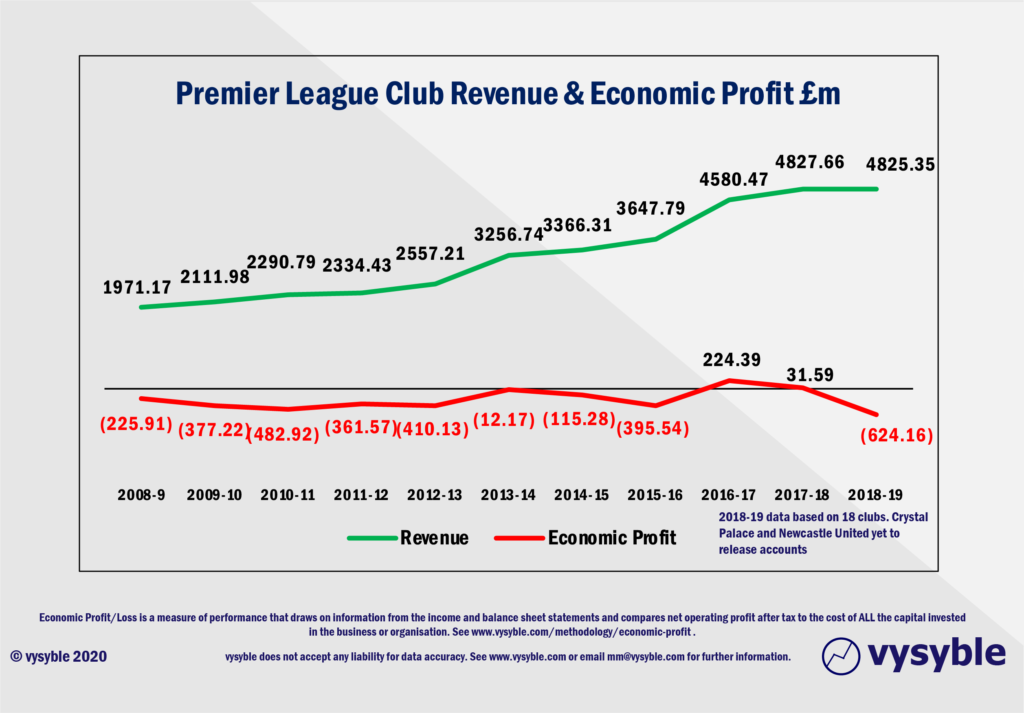

Set out below is the year-by-year economic performance or track record for the English Premier League from 2009 to 2019 (we do not have all of the 2018-19 accounts but we are in this example interested in the directional signal).

The above graphic tells us is that when all of the costs of doing business are included, particularly the cost of that all-important owner-derived equity capital, the overwhelming picture is that clubs are clearly not covering their costs and the average participant in the EPL over an 11-year period is running at an economic loss and destroying value.

The numbers are collossal:

Since 2009 (to date), Premier League Club revenue amounts to £35.769bn

Since 2009 (to date), Premier League Club economic losses are £2.748bn

There is little doubt in our minds that football’s financial crunch has been brewing for a number of years (see media listing) though the COVID-19 outbreak has been the most unfortunate of catalysts.

However, the powers that be in the game have chosen not to recognise the underlying financial threat that we have continually warned about since 2016. Our view has always been that any threat to the TV money would be highly detrimental to the financial well-being of the clubs.

‘Clubs are not-for-profit, clubs are not businesses, you are using the wrong measure, it is not applicable to football….’

In the modern era, a football club cannot function as a community asset if it is unable to function financially. That is the harsh reality. Indeed, we have yet to be informed as to what is an acceptable loss for a football club although our 2018-19 data for the Premier League and Championship clubs suggest a combined and record-breaking economic loss of almost £1bn might be over-doing it….

We have used the following quote from Peter Kontes in previous blogs but it remains a very good summary of the current position:

‘It is not too strong a statement to say that without Economic Profit measures, a proper managerial understanding of the strategic position of a business and the strategic options it faces would be nearly impossible…

In organisations where the overall economic performance is negative on an on-going and consistent basis then the outcome is rarely favourable particularly for the shareholder over the longer-term. To be blunt, there is no balance sheet big enough to withstand consistent and large economic losses on the scale frequently encountered in industries with poor economics.’

Frequently, we have demonstrated that the English Premier League club financial dynamics are challenging and overly-reliant on TV contracts along with increasing costs associated with players and player transfers.

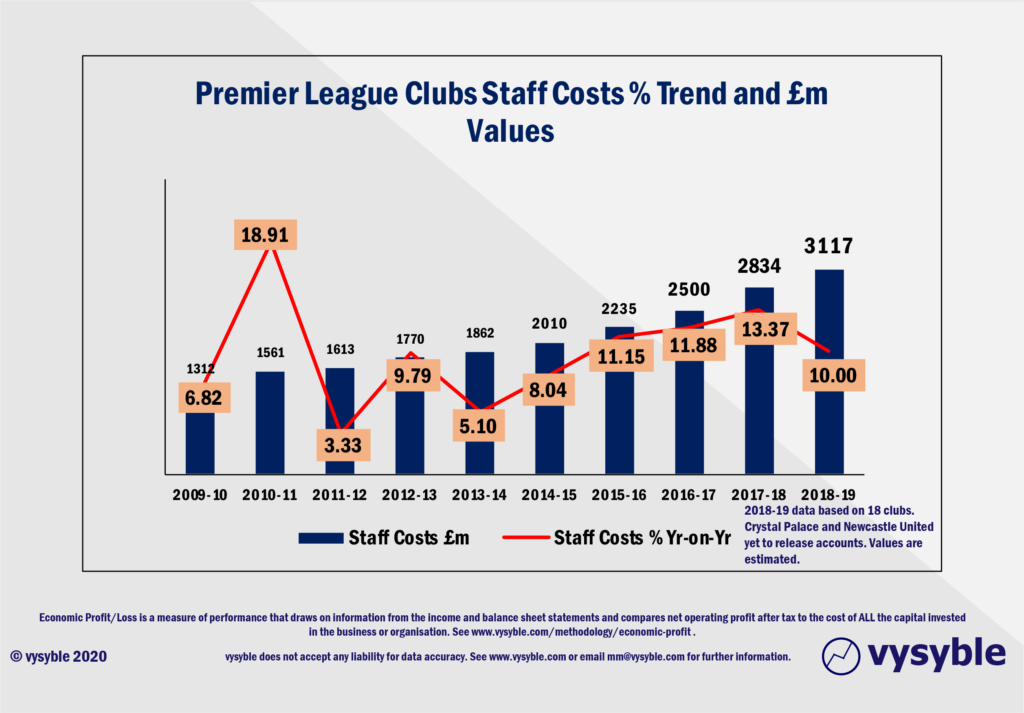

As the above graphic highlights, Premier League staff cost increases have been substantial both in percentage and £ value terms. The vast majority of the staff cost values will be the players.

60% of the Premier League’s club revenues (as of latest 2018-19 data) is spent on staff costs. In the Championship, staff costs are running at 104% of revenue as of the latest 2018-19 data.

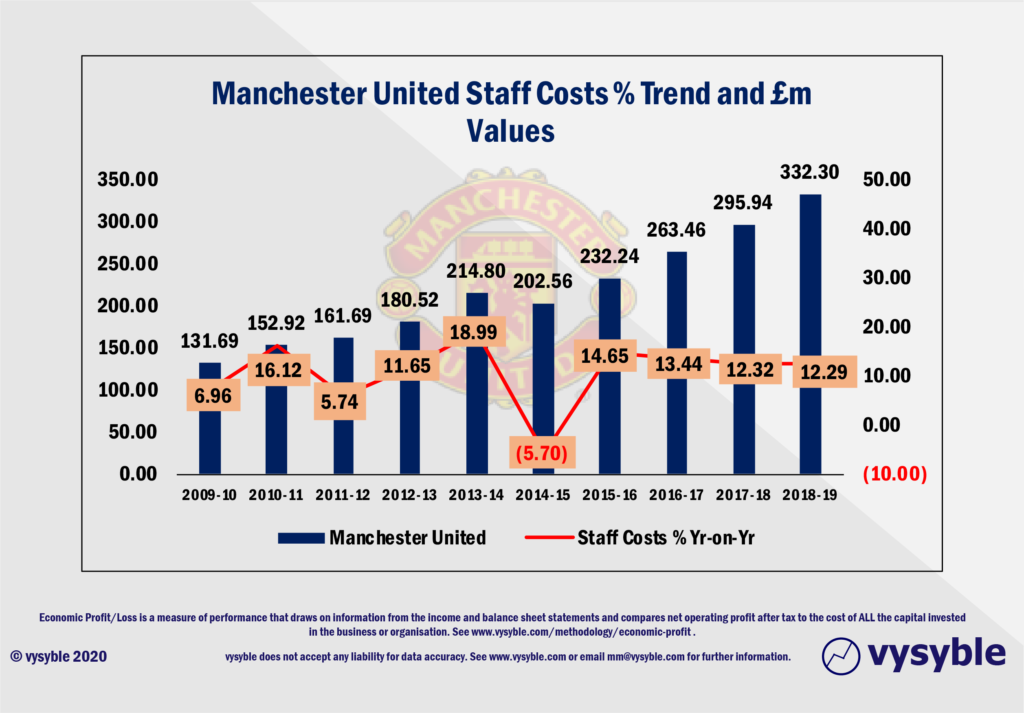

The club with the largest staff cost bill is Manchester United.

Indeed, when we look at the club’s overall financial performance, we can see the effect it has had on the overall cost base.

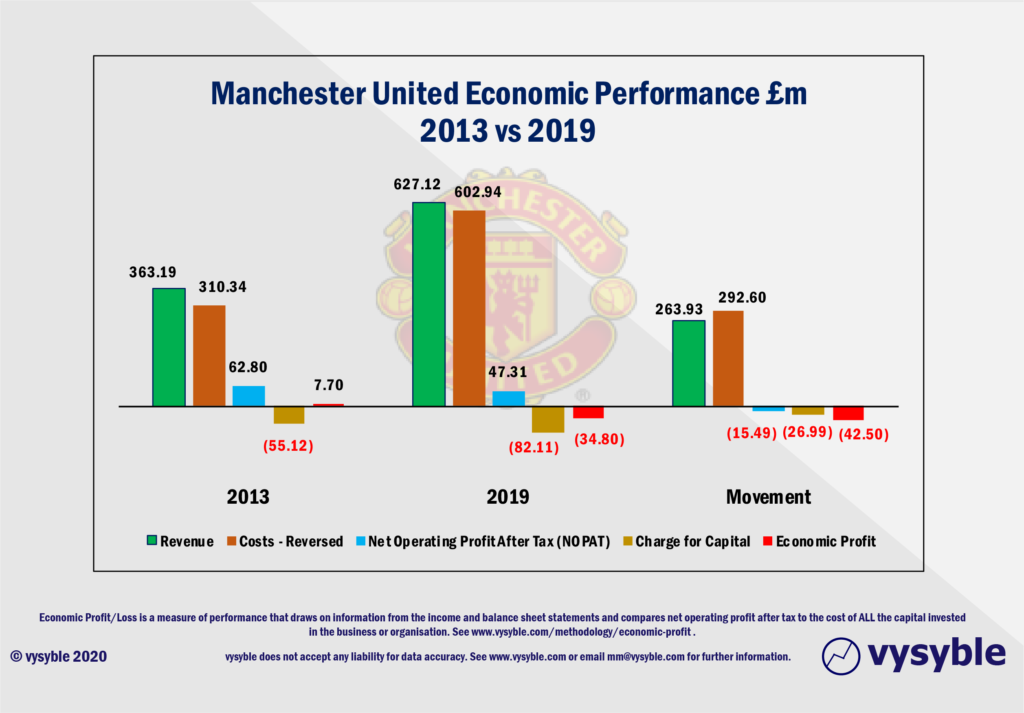

In 2013, the club earned £363.2m in revenue with costs amounted to £310.3m. When the profit from player sales, tax and the charge for capital is deducted, the club achieved an economic profit of £7.7m. This was the last time that the club posted an economic surplus.

By 2019, revenue had risen by £263.9m to £627.1m. Costs amounted to £602.9m. The charge for capital had grown to £82.11m. When the profit from player sales, tax and the charge for capital is deducted, the resulting economic loss was £34.8m. Therefore, between 2013 and 2019 the club’s revenue has risen by £263.9m but the costs of generating that revenue have risen by £292.60. In other words, the cost base including tax has risen by £30.5m more than the impressive revenue increase.

Conclusion

Our data has explicitly demonstrated the extraordinary lengths owners will go to in the pursuit of trophies, status, promotion and the avoidance of relegation, all to the potential detriment of the long-term financial well-being of the football club itself.

Players and their agents do not make the final decision in terms of what they get paid. That is down to the owner and his/her senior management team. If a player can get a better wage as a result of contractual negotiations then all well and good in our view as long as the owner and the club can afford it. And that has been the problem. In many cases, the club cannot afford it but it still happens.

When a Championship club like Reading FC can turn in a staff cost to revenue ratio of 193% based on the latest financial data, it becomes clearly evident that something is very wrong.

Clubs have entered into contracts with the players and, in our view, if clubs want a deferral or a reduction in wages then that would require a variation of terms or more likely a new contract. All in all, this is perhaps not quite as simple as Mr Hancock might have initially understood.

Similarly, club owners faced with no money coming in from TV along with onerous contractual obligations to their key resource ie the players, are clearly caught in something of a bind. Even worse, it is possible that the value of their playing staff could fall which in turn raises the potential of a financial crunch where the value of the playing asset falls below the (potential and short-term) loan taken out to purchase it. In this scenario, whatever moral misgivings we might have, one can see why with no apparent end in sight, clubs are taking advantage of every opportunity to minimise cash outflows.

The economic profit profile tells us that club owners have been increasing their capital contributions in order to keep alive whatever trophy-laden dreams they had. Unfortunately, that dream has now turned into a massive financial and economic nightmare.

Finally, the German economist, Rudiger Dornbusch described Mexico’s economic crisis in the 1990s:

“The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.”

We do fear that the crisis which the game’s administrators and club owners have ignored (despite our protestations) for a number of years is now very much with us.

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter