9th October 2018

As much as we get asked the question ‘What do you do?’ we invariably find ourselves explaining why we do it. When we mention Matchday Data as a constituent element in that explanation, the listener usually expresses a modicum of surprise as to why it hasn’t been done before.

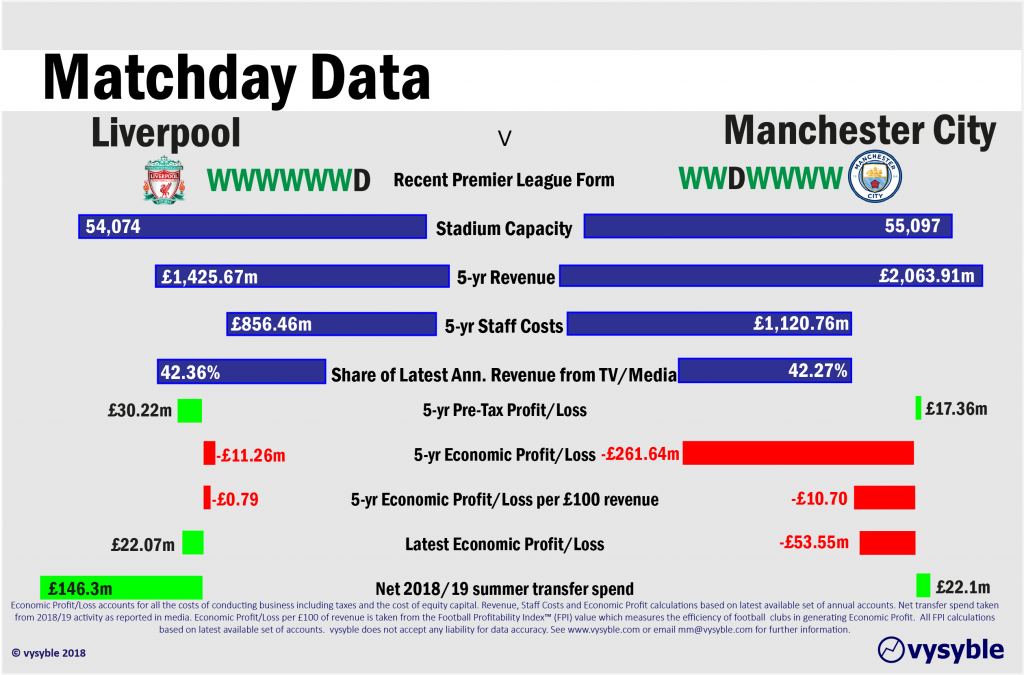

For those of you who don’t know, Matchday Data is our summarised financial preview of each Premier League fixture in an easy-to-read format. Hitherto, it is distributed via Twitter (@vysyble).

An example of the Matchday Data format.

The reason ‘why’ is very simple – a belief in transparency combined with a deep love of the beautiful game. The more we analyse football club financials, the more obvious it becomes to us that the economic performance of football clubs is a key ingredient in determining on-the-pitch outcomes. Indeed, within our work we have found a more than casual relationship between relegation from the Premier League and the condition of a club’s finances and its economic performance. A lot of football fans tell us that intuitively they had always believed this to be the case and accordingly the club’s financial strategy has to play a part in the overall “football success” equation.

In our consulting activities we frequently use examples from football to explain specific points or to highlight aspects of a particular business strategy or a market dynamic. The reaction is usually one of surprise. The wider public, along with some within the media, understandably conflates marketing reach with value creation and consequently perceives football to be highly profitable and awash with cash. Well, one of these assumptions is correct but sadly it is not the former. Football is a sport that does capture attention but increasingly we find that the hidden recesses of its financial picture is gaining more interest as we continue to dig deep.

The economic profit metric is central to what we do because it has repeatedly proven to be the most informative and rigorous benchmark in measuring business performance. Furthermore, when the principles of economic profit are applied to business strategy, the transformation can be spectacular. The few business tomes that do mention economic profit usually cite the example of Coca-Cola under the stewardship of Robert Goizueta. The late Mr. Goizueta implemented an economic profit-driven business strategy under which the company’s share price grew a not-so-modest 7,200% during his tenure.

English football has changed markedly since the formation of the Premier League in 1992. The senior division has capitalised upon its appeal through successive and lucrative media rights deals to the extent that annual Premier League club revenues exceed £4.5bn (2016-17). All clubs that now participate in the Premier League will turn over a 9-figure sum so from a business perspective, these are significant economic entities managing huge budgets and commitments.

Whether the league itself is more competitive is perhaps open to question – since the formation of the EPL in 1992-93, some 25 seasons ago, six clubs have won the title of which two – Leicester City and Blackburn Rovers – managed a single success. To put it another way, in 23 of the last 25 seasons the title has been shared between four clubs; Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United. Contrast this with the old English First Division over the previous 25-season period from 1967 through to the formation of the Premier League in 1992 – nine clubs in total won the title with six accounting for 21 successful campaigns. The full list is as follows; Arsenal (1971, 1989, 1991), Aston Villa (1981), Derby County (1972 & 1975), Everton (1970, 1985, 1987), Leeds United (1969, 1974, 1992), Liverpool (1973, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, 1982-84, 1986, 1988, 1990), Manchester City (1968), Manchester United (1967) and Nottingham Forest (1978).

In more recent times, the biggest clubs by revenue (Manchester United and Manchester City) enjoy a combined turnover in excess of £1bn (2017-18 accounts: Manchester United £590.02m, Manchester City £500.46m). The remaining members of the so-called ‘Top 6/Big 6’ group – Arsenal, Liverpool, Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur – earned £1.46bn in revenue in 2016-17. In fact, the biggest 6 revenue-earning clubs account for almost 55% of total divisional revenues. Dominance on the pitch starts from financial imbalances off it or, to put it another way, perhaps the financial football playing field is not as “level” as some would have you believe.

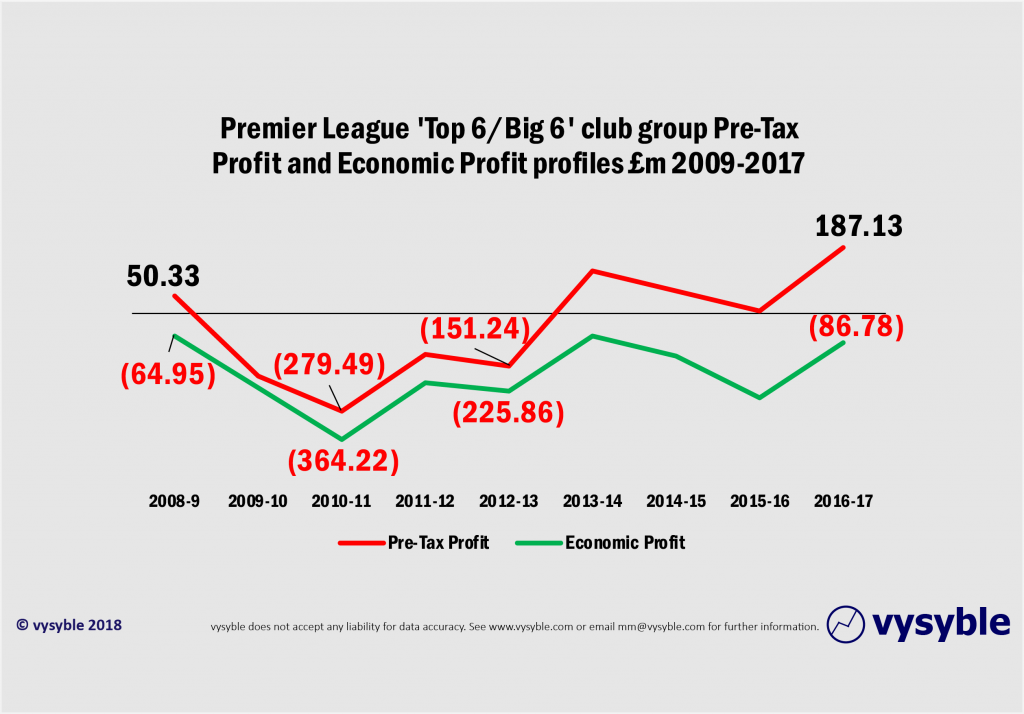

Despite this, the economic profit picture for the six clubs is poor. As a group, it has failed to achieve a single economic profit since we started monitoring the data in 2009. The lack of an economic profit means that as businesses they are not covering all of the costs of doing business – including tax and a charge for ALL of the capital required by the clubs.

At a more granular level, Chelsea and Manchester City have failed to post an economic profit since 2009, Arsenal since 2010 and Manchester United since 2013. Indeed, given the 54 opportunities to achieve an economic profit between 2009-2017 for the six clubs, the reality is that there have been only 11 instances, 7 of which can be attributed to Tottenham Hotspur (4) and Manchester United (3).

Unfortunately, the commonly used Pre-Tax profit number does not go deep enough into the performance of the business as it does not cover ALL costs and charges. Viewed through the Pre-Tax lens one might conclude that Arsenal is highly successful off-the-pitch (£230m of accumulated Pre-Tax profits since 2009) but then add in the tax and a charge for all the capital used by the club and the position changes to a cumulative economic loss of -£133.42m. Sadly, this is not an untypical situation.

Both Manchester City and Manchester United have released their 2017-18 accounts. Combined Pre-Tax profits = £36.54m. Combined Economic Profits = -£94.61m

There are indeed some clubs that are run exceptionally well and achieve economic profit more often than not – Tottenham Hotspur as mentioned is a notable example along with Burnley and Everton. Despite the rises in media rights revenue, football is, even at the uppermost levels of the game, generally an economic loss-generating enterprise.

It is this point which persuades us to provide supporters and fans with the financial data associated with their club and others within the division on a regular basis. It could be argued that it is not in the interests of the Premier League to divulge what has been a fairly poor run of club financial results over the last 9 years, nor is it in its interests to have this information presented back to supporters on a regular and weekly basis. Certainly, our own experience in dealing with the Premier League (and the EFL) is that it would very much like us and our work to go away.

Nevertheless, in the interests of transparency, it is the right thing to do in order to raise awareness amongst the faithful who spend their hard-earned money supporting their club. The underlying economic profit patterns reveal just how vulnerable this sporting ecosystem really is to the whims of the so-called “richer” clubs. In addition, we feel that it is vitally important that there is a mechanism by which fans can see just how their own club is faring against the opposition both on and off the pitch and on a regular basis too.

The proof is that Matchday Data has become the most interactive thing that we do online. Whilst we might not currently enjoy thousands of followers on Twitter (our output is predominantly about finance and company performance…), the achieved impression (no. of eyeballs) and engagement levels have been steadily increasing since the start of the season. We also follow each weekend with the Premier League table along with a highlighted economic/financial theme. The table, it is often said, never lies, but then neither does the economic performance.

We like to think that the message is starting to get through that the financial position of the clubs will dictate the future direction of English and European football. La Liga clubs playing in the US are doing it for a reason that is purely financial. A European Super League will happen because of the potential financial gains to those clubs that found it.

Long gone are the days of parochial patronage. Today’s football is about social media reach, Asian fan numbers, sponsorship deals and marketing platforms. At least with the Matchday Data service, the average supporter can see just how that money is being spent/squandered and just how predictable the Premier League has become as a result.

You can access Matchday Data on Twitter via @vysyble or #matchdaydata

vysyble