8th February 2020

Sir Alex Ferguson’s famous phrase ‘squeaky bum time’ has rightly passed into the litany of football if not the country’s wider dialectic. The phrase itself seems to have originated as a line in one of Sir Alex’s numerous observations towards the end of the 2002/03 season when Manchester United and Arsenal were vying for the Premier League title.

As reported in the Daily Express…“They [Arsenal] have a replay against Chelsea and if they win it they would face a semi-final three days before playing us in the league. But then they did say they were going to win the Treble, didn’t they? It’s squeaky bum time and we’ve got the experience now to cope.”

17 years later, the world of the Premier League is a very different place. No club earns less than a 9-figure annual revenue, the adoption and implementation of VAR remains problematic whilst the financial influence of the Champions League threatens to drive further financial wrecking balls into an already fiscally-polarised division.

Nevertheless, the Premier League is an entertaining and almost spell-binding proposition as long as you support or at least show an interest in a team outside of the top six clubs by revenue. Why? With three of the four longest unbeaten runs from the start of the season taking place in the last three years, the title race is in danger of becoming less of a race and more of a procession.

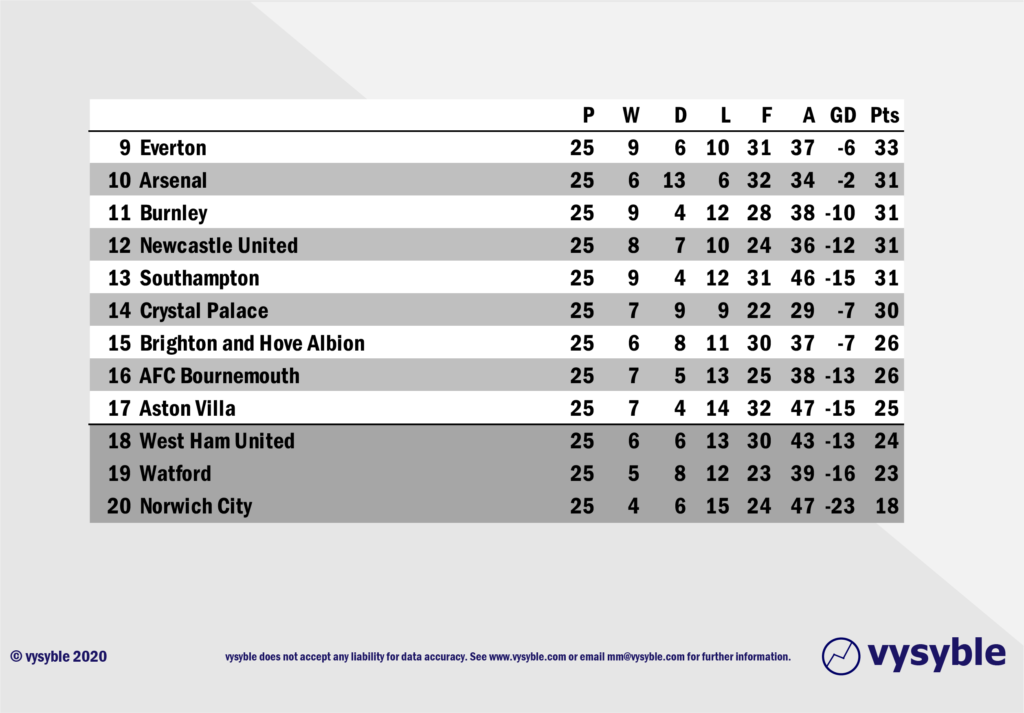

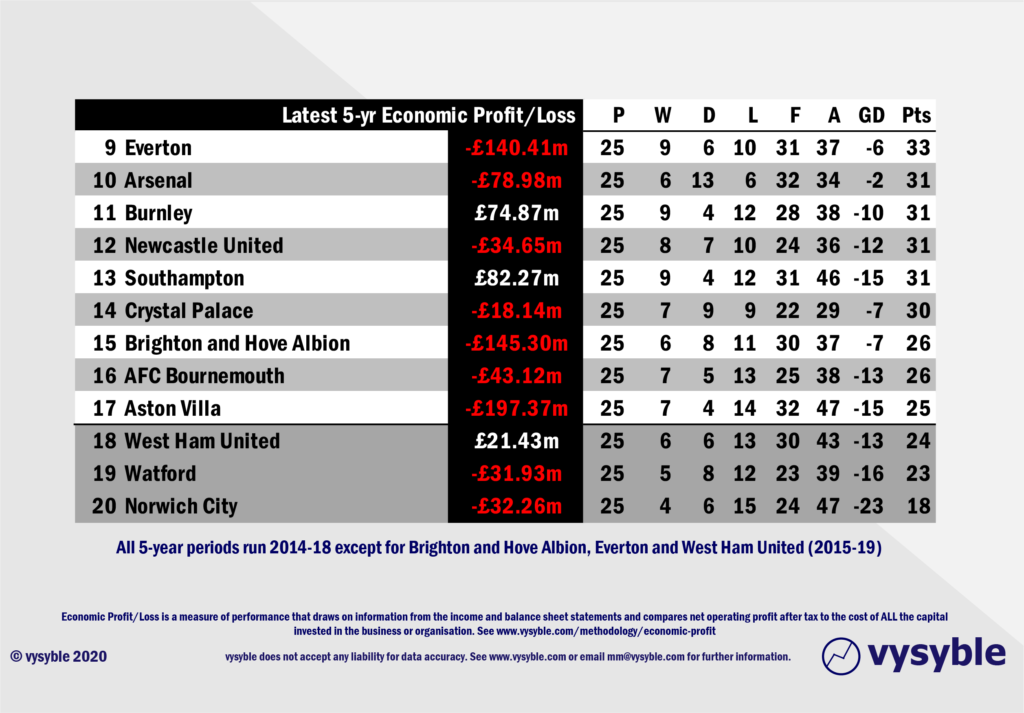

Arguably, the real entertainment is to be had at the other end of the table. With 25 games played at the time of writing, the battle to remain in the division is getting very interesting indeed. Any of the teams lower than 9th place (Everton) could, with a bad run of results, end up in the mire. So let’s take a look at the table to see the cast of characters…

In our analytical view, the table does have a certain look about it. For example, one in three clubs promoted from the Championship is usually relegated from the Premier League in the first season so to have Norwich City, promoted in 2018-19, propping up the table is not entirely unexpected.

We also see fellow promotee Aston Villa positioned perilously close to the drop zone. To have two promoted clubs enduring relegation after a single season in the top tier is most unfortunate but it has occurred twice in the last three seasons ie 2016-17 and 2018-19, so again we shouldn’t be too surprised if the trend continues.

Other Relegation Benchmarks

In order to remain in the Premier League, achieving 17th place is good enough. Therefore, clubs have to beat the 18th– placed performance, ideally with a greater points haul but it could just as easily come down just to goal difference. Here are the points totals following 25 games and the final tally for 18th place in the Premier League since 2001.

The average points haul at the 25-game position is 22 and the average finishing points haul for 18th place is 35 – the difference of 13 points is a point for every remaining Premier League fixture at this stage.

Arguably, clubs could set themselves a safety target of 24 points (current 18th place total after 25 games) +13 points (average difference between 25 and 38 games for 18th place) +1 point = 38 points.

How valid a 38-point target is will only be known at the end of May.

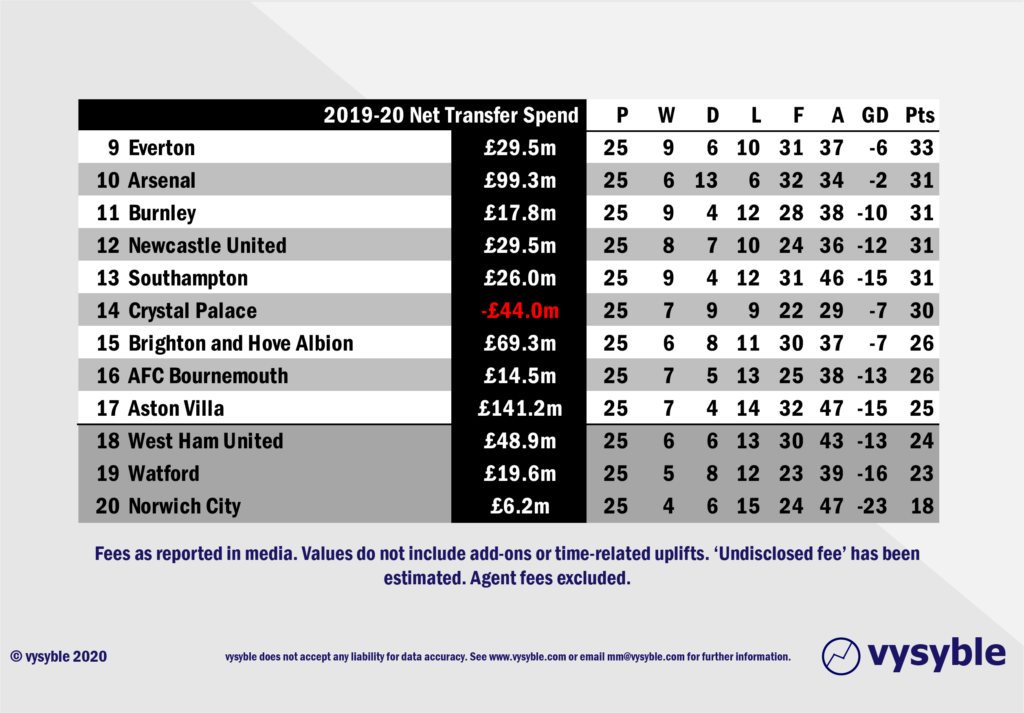

However, another look at the table with net transfer values for 2019-20 for each club provides a deeper insight into what is going on behind the scenes.

Two aspects stand out immediately:

- Firstly, Aston Villa’s £141.2m net spend is the largest net spend for a promoted club into the Premier League and significantly ahead of Fulham’s £96.8m spend for its single Premier League season of 2018-19.

- The second aspect is Crystal Palace with a net profit on transfers of £44m. Fans may question why run such a sizeable net profit when strengthening the team and Premier League survival is perhaps the greater priority. One clue may be the sizeable losses made by the club in 2017-18 i.e. a pre-tax loss of £35.54m and, more importantly, an economic loss of £39.14m. With a net transfer spend of £9.3m in 2018-19 (full accounts for the year are not available at the time of writing), the overriding objective at the club would at this point in time appear to be to balance the books whilst ensuring Premier League status – a difficult task but not impossible.

Of course, the accountants’ view is that the purchase cost of a transfer can be amortised (spread out) over the length of the contract term thus giving the impression that the expensive big money signing is more affordable than it really is. However, the player’s wages and associated costs cannot be treated in the same manner. There is only so much the accountants can do to ‘smooth the view’.

Contrast this with Aston Villa’s exceptional spending levels and its challenged financial track record ie £187.09m in pre-tax losses and £197.37m in economic losses between 2013-18. Plenty has been written about the club’s issues with the EFL’s version of Financial Fair Play but relegation into the Championship will. in our view, be a financial nightmare for the club. It is one thing to bring to recruit in excess of £140m of talent but it is quite another to unwind the associated staff costs when facing a potential 50% overnight decrease in revenue upon relegation.

The Relegation Dynamic

The world of relegation is not a comfortable environment. Between 2009-19 there have been 33 instances of relegation into the Championship with accounts released so far for 27 instances relating to the year following relegation. Out of those 27 balance sheets, 24 achieved economic losses notwithstanding the much criticised parachute payment scheme. Swansea City’s very recent financial statement highighted a pre-tax loss of £7m in its first season back in the Championship (we require the full balance sheet to calculate economic profit). Adjusting to life in the EFL comes with a heavy price as indicated in the table below.

Ideally, you would like to believe that the clubs are fully prepared. Then again…

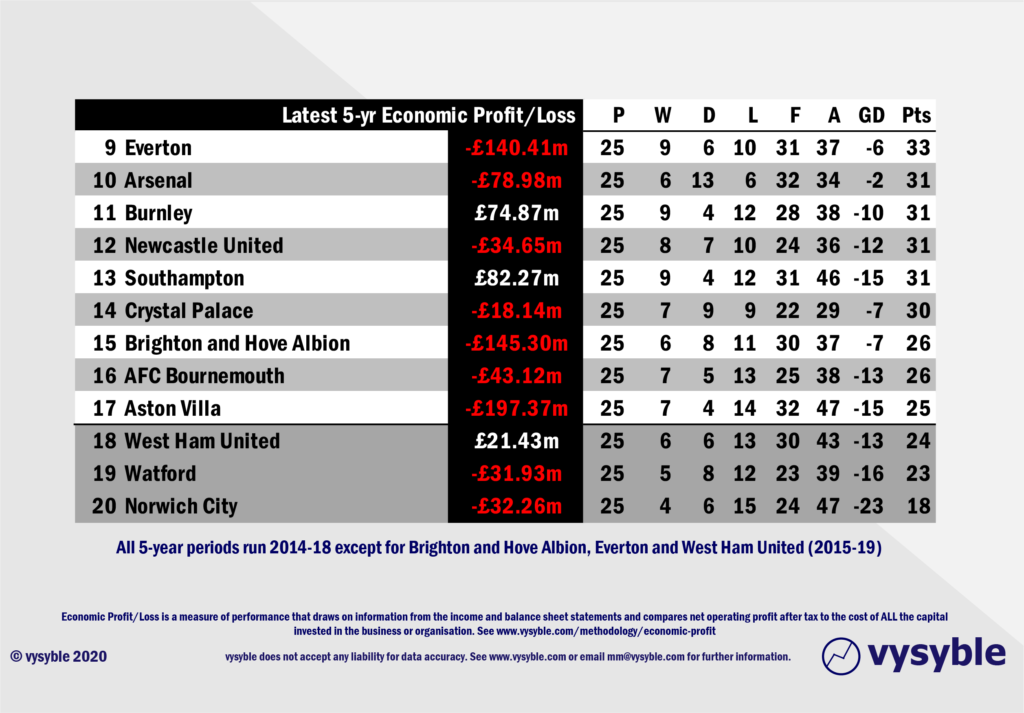

However, when we total the economic profit/loss values over the most recent 5 years of available accounts, together with the high probability of a post-relegation economic loss, one has to conclude that the outlook is considerably gloomy for what is in the main an already economically challenged group of clubs.

It may be surprising to some to observe the relative lack of economic profitability. As the majority of our work over the last 3-4 years has shown, football in general is anything but value creating.

The recent 5-year economic performance reveals that both Aston Villa and Brighton & Hove Albion have significantly more to lose than most. Together, the Villans and the Seagulls have spent a massive net £210.5m on transfers, representing 26.6% of the Divisional total in 2019-20, just to stay in the Premier League. If Aston Villa do fall victim to the dreaded drop, potentially there could be a lot more to say goodbye to than just Jack Grealish.

Therefore, questions must be raised about the sustainability of such high overall spending levels coupled with deepening losses over time.

The TV Cycle and Club Economics

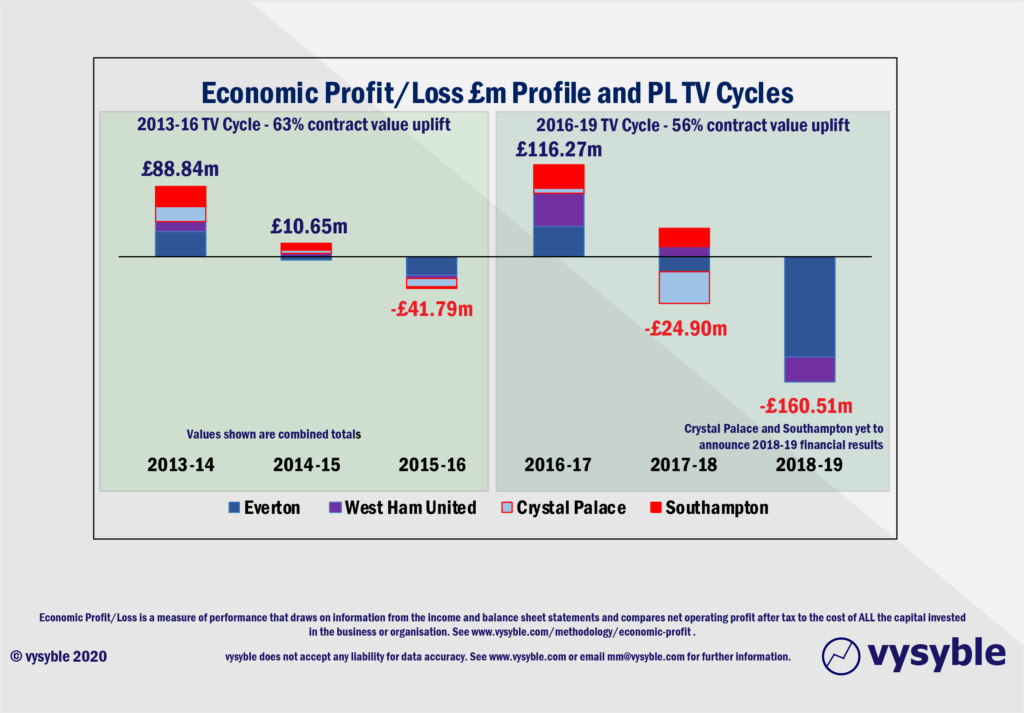

At the time of writing, the majority of clubs in the lower half of the table (as depicted above) have yet to declare their 2018-19 accounts. We expect to see increased economic deficits. Why? 2018-19 is the last year in the Premier League’s 3-year TV cycle. Here is how it works.

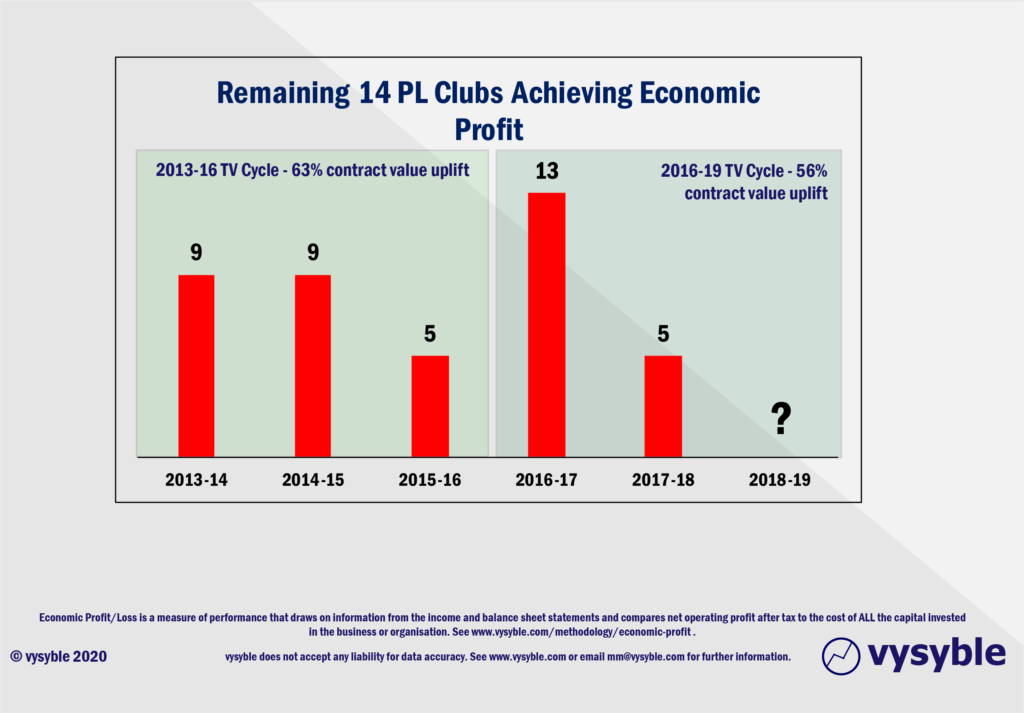

The 2013-16 and 2016-19 cycles delivered overall value increases of 63% and 56%. Clubs without access to European competition and its increasingly generous participation/prize money experienced a significant jump in revenue and profitability in each respective first year of the cycle.

However, by the third and final year of the cycle, profits turn into losses notwithstanding the higher revenue levels. We observed this with the 2013-16 cycle and reported our findings in 2017 and 2018 by which time details of the 2019-2022 TV cycle for the domestic portion had been announced with an estimated 10% decline in value.

Given that by 2018 we were already seeing the pattern of 2013-16 being repeated for 2016-19, we said…’We expect the general economic position of the majority of clubs to deteriorate over the next five years…’

Furthermore, as the 2018-19 accounts are in the process of being released, we have already seen some significant falls in economic profitability across the two cycles as illustrated by the following graphic which details the four clubs – Crystal Palace, Everton, Southampton and West Ham United – outside of the ‘Big 6’ by revenue to have remained in the Premier League between 2013-19.

The pattern is familiar ie profits in year 1 moving to losses in year 3. The second cycle, however, is showing a very worrying degree of deterioration in economic performance when compared to the previous cycle as highlighted below.

West Ham United

And so we come to West Ham United, the stand-out occupant of 18th place in the Premier League and apparently the 19th highest earning football club by revenue in the world according to a certain firm of auditors.

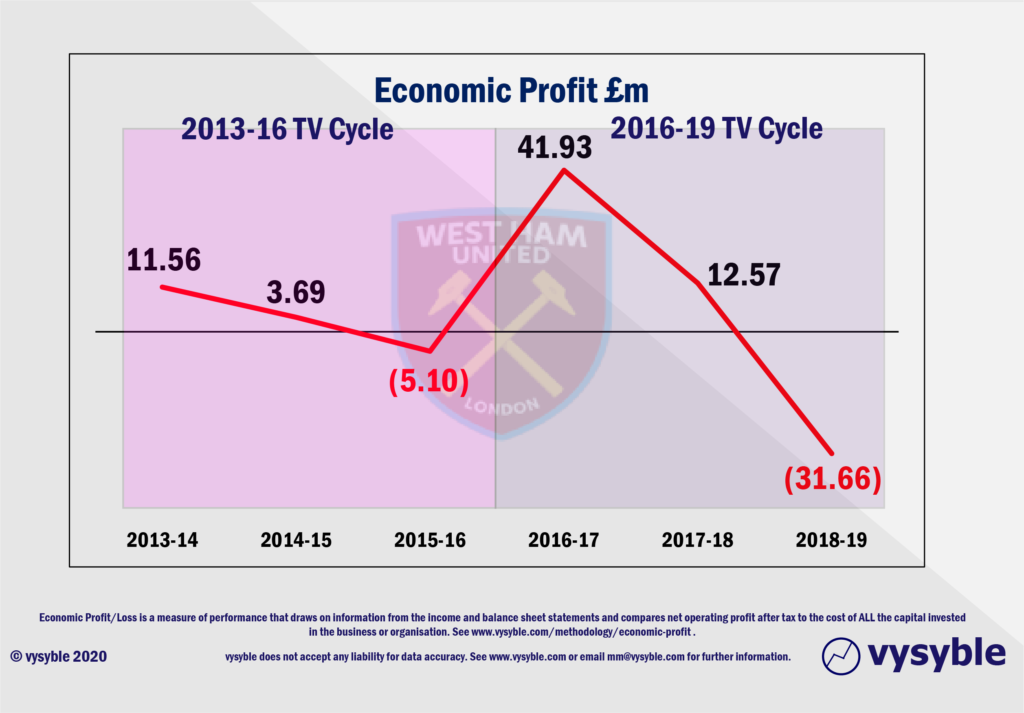

The economic profit performance of the club fits the TV Cycle economic profit-to-loss pattern, as can be seen below.

Perhaps the 2018-19 outcome would have been very different if the Directors had read our reports in 2017 and 2018 and taken note of our observations. Then again, “you can’t manage what you can’t see” and if you are using incomplete accounting metrics then it is unlikely that the above picture would have been forthcoming to them. Aspiring ‘apprentices’ take note.

The numbers reveal a potential lack of understanding of the overall market dynamic. For example, during the 2016-19 TV cycle, club revenue over the three-year term rose by just 4% (£7.36m) yet staff costs were allowed to rise by 42.8% (£40.75m) to £135.80m. This in turn resulted in a staff costs to revenue ratio of 71.21% , just above UEFA’s recommended safe limit of 70%. The last time that the club had a ratio of 70%+ was in the promotion-winning season of 2011-12 (90.21%).

In 2018-19, the club had a net transfer spend of £79.6m which was the fourth highest in the division behind Chelsea, Liverpool and Fulham. For a mid-upper ranking revenue club in the Premier League and in the last year of the TV cycle, increasing costs in such fashion reversed an economic profit of £12.57m to an economic loss of £31.66m. Is this a strategic blunder by the board of directors or a club showing the degree of its ambition?

The next TV cycle (2019-2022) has achieved an overall 9% uplift in overall value despite a fall in the value of domestic rights when compared to the previous cycle. This obviously is a far cry from the historical uplifts of 63% and 56%.

Indeed, we published a blog about it at the time and said… ‘we stated very publicly that the economics of the Premier League were extremely vulnerable to a shock such as a fall in TV income given the reliance on this revenue stream and the general behaviour of most of the clubs in their overspending. That shock seems to have arrived. The lifeboat has failed to sail.‘

Without a change in approach, the economic losses, in our view, will continue to increase at West Ham United. With an additional net transfer spend of £48.9m for 2019-20 of which £22.8m occurred in the January 2020 window (4th highest winter net spend behind Manchester United, Tottenham Hotspur and Sheffield United), the intent to remain in the Premier League is clear. However, we have also seen numerous examples of clubs overspending in order to preserve their Premier League status only to fail and then flounder further in the Championship as attempts to repair the balance sheet overwhelm their ability to compete on the pitch and push for promotion back to the ‘promised land’…

If West Ham United preserves its Premier League status, it will face relatively flat revenues up to 2022 unless it can find new sources or qualify for European football. At the same time, something will have to give in costs in order for the club to return to profit.

We surmised earlier that 38 points might be a viable target for Premier League survival. If we take another look at the lower half of the Premier League table and the 5-year economic performance, 38 points and likely survival is anywhere between 4 and 7 wins from 13 games for the bottom six clubs.

Anything less and the financial carnage of the EFL Championship awaits – squeaky bum time indeed…

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter