3rd August 2018

Introduction

Bill Gates has described the book “Factfulness” by Hans and Ola Rosling as one the of most important books he has ever read and an indispensable guide to thinking clearly about the world. The tome’s basic argument is that the world is in much better shape than the media and our own in–built prejudice relating as to how the world works would have us believe.

In the book the principal author, Professor Hans Rosling, poses 13 questions to demonstrate this view. Evidently, extensive sampling shows that most people answer the questions incorrectly. He then compares these results to that of a chimp which has managed to answer the same set of questions but with complete randomness. Just when you are beginning to feel better about the world, the chimp answering said set of questions tends to return better scores than most human adults.

Despite the memorable opening of the film 2001 – A Space Odyssey, the superior result for the chimp is not down to some higher cognitive processing power or entity. The result is a consequence of a deeply held but an ultimately wrong “understanding” regarding the world around us. Indeed, Professor Hans Rosling offers ten separate instincts that distort our perspective and which prevent us from seeing the world in a more evidence-based fashion.

With this in mind, it is worth taking a look at the UK commercial property market and the retail sector in particular. One of the major market participants – Hammerson plc – has been in the news recently for all of the wrong reasons.

Hammerson’s CEO David Atkins positions the company as “best in class.” This perspective is open to question given that the share price has fallen by over 10% in the past year coupled with an aborted attempt to acquire Intu – a company with its own challenged record of returns on the capital markets.

Evidently shareholders did not share Mr Adkins enthusiasm for “scale” as a route to outperformance and the takeover was soon abandoned. Furthermore, prospects across the UK’s retail landscape have since darkened significantly and the asset valuation “push” from quantitative easing has probably run its course as interest rates move increasingly in an upwards direction.

In fact, retail property asset valuations, even for “dominant centres”, will probably fall significantly in the next 18 months. Consequently, and in an effort to turn things around, the company has undertaken to sell £1.1bn in assets just when the investment market for retail shopping centres is clearly softening.

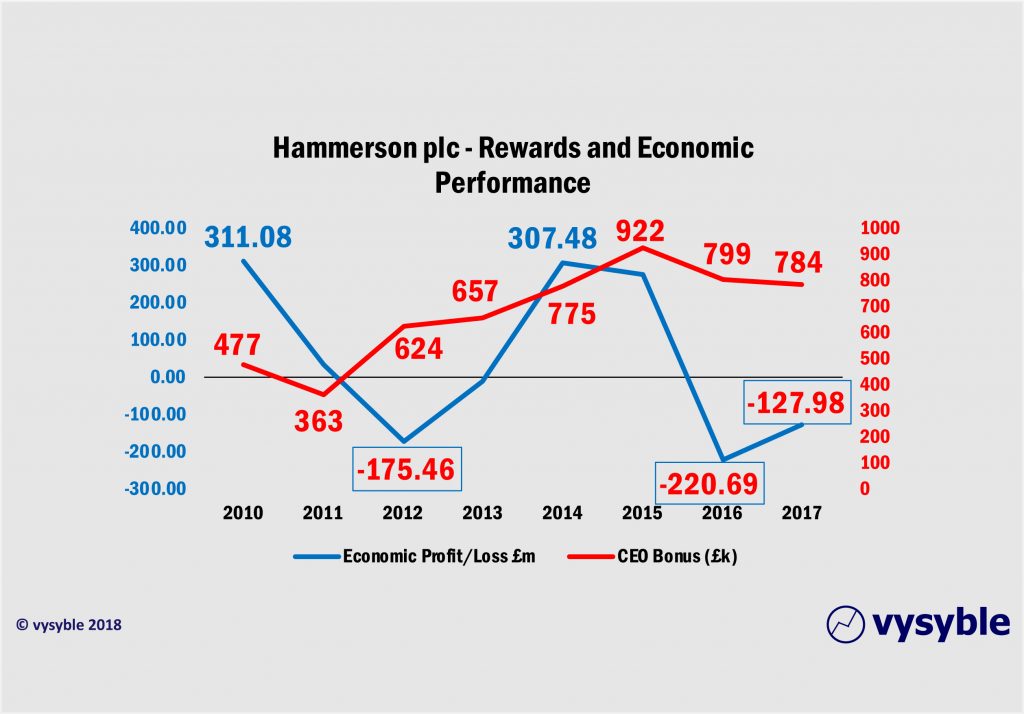

It is tempting to believe that this is a temporary, recent or short-term problem. However, our experience tells us that it has been brought on or induced by a misguided view of what value creation for shareholders entails and what the best surrogate over time for the trajectory of the share price might be. In this sense there are parallels with the work of Professor Hans Rosling. The issues are not due to a lack of “cognitive power” but more as a result of historic and out-dated perceptions of what drives value for real estate investment companies on the capital markets.

What do we mean by value creation?

Observers may argue that Real Estate is not always at its best in absorbing new ideas from other industries and academia. With that in mind, we will use an old definition of value creation from Alfred Marshall and his book “Principles of Economics” published in 1890:

“Value is created by investing capital and generating a return greater than the cost of that capital”

Alfred Marshall – Principles of Economics (1890)

Unless we include all of the costs of doing business, including the cost of shareholder’s equity, we are not complying with Alfred Marshall’s definition of value creation.

Some industry stalwarts have argued that real estate is a “special case” or that Marshall’s definition somehow does not apply. This seems to be based on the in-going assumption that commercial property has a different economic gravity to other industries – an understandable assumption for those steeped in real estate but one that is best filed under the folder “complete nonsense.”

Hammerson

With a business model based on “buy and hold” when yields for dominant shopping centres are typically sub-4.75% (Knight Frank June Yield – June 2018) along with a cost of equity north of 8%, the ability to sustainably create value for shareholders over the longer term must be a titanic struggle. Of course, the accounting returns show a more positive picture but then modern financial accounting practice, for perfectly legal reasons, takes the perspective that shareholder’s equity is apparently free.

In other words, there is a cost for shareholder equity but because of a combination of history and possibly the perceived degree of difficulty in establishing quantum, it is not acknowledged. Despite industry folklore, this is the primary reason for the “discount to net asset value” and is the heart of the reason behind the power of using an all-embracing metric like economic profit, a performance measure which includes ALL of the costs of doing business, as the principal driver of strategic formulation.

The disparity between the share price and the typically higher net asset value per share for companies like Hammerson can lead to a debate regarding which of the two approaches gives the true value of the business.

On the one hand, we have the accumulated wisdom of the capital market – from the multitude of investors who express a daily view on the future performance of the business through the share price. Against this, the primary component of net asset value is the valuation of the company’s real estate holdings. This is a relative valuation undertaken by specialists based on comparable evidence. Experience tells us that when an organisation becomes an acquisition target, the share price of the target tends to move towards the net asset value per share.

In fact, both numbers are correct – the share prices of real estate investment companies tend to be lower because the capital markets are pricing in the economic deficit from real estate retention over the cycle and the valuation underpinning net asset value tends to reflect current market conditions – so when an investment company like Intu becomes an acquisition target, the capital markets are behaving quite naturally as the share price moves upwards and towards the net asset value in anticipation that market value will be realised.

Much of this could be “bottomed out” or resolved by taking an economic perspective of the business. Experience also tells us that the debate can quickly turn to what is the appropriate cost of capital, a subject that is obsessively close to many a real estate investor’s heart. The detail is important but more importantly it is the ability to focus on the broader economic signal, which invariably shows that over the cycle, value destruction is more likely than value creation.

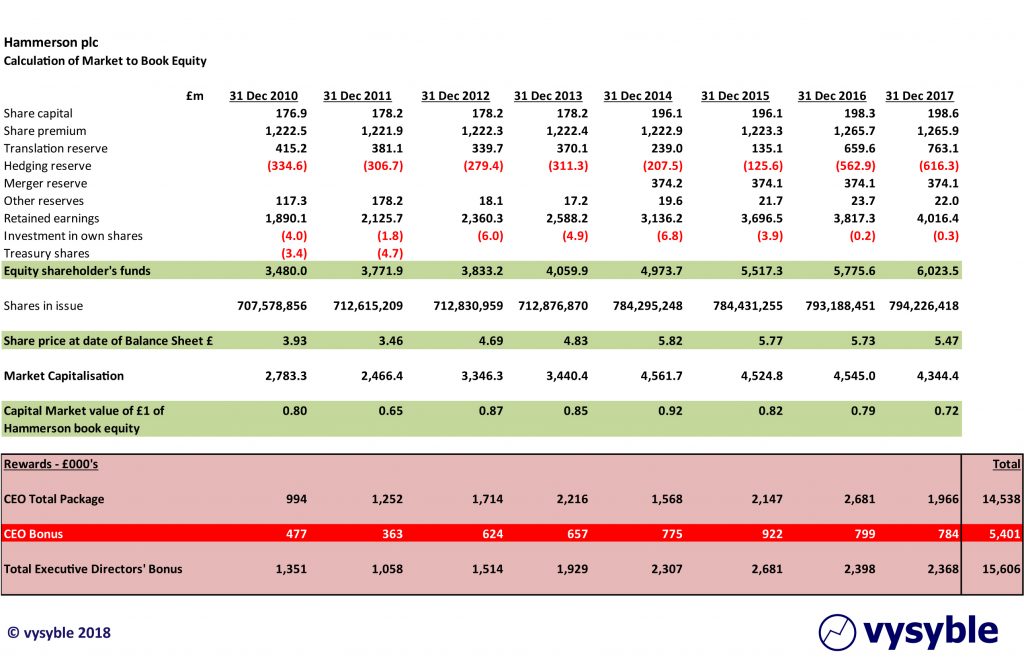

So let’s try a different approach and one that does not include an assumption for the cost of capital. There is only one share price at the end of a given day’s trading and the balance sheet is prepared by the company, audited and typically signed by the CEO and Finance Director. Set out below is the shareholder’s equity for each balance sheet going back to 2010 and the relevant closing share price together with the market capitalization for Hammerson.

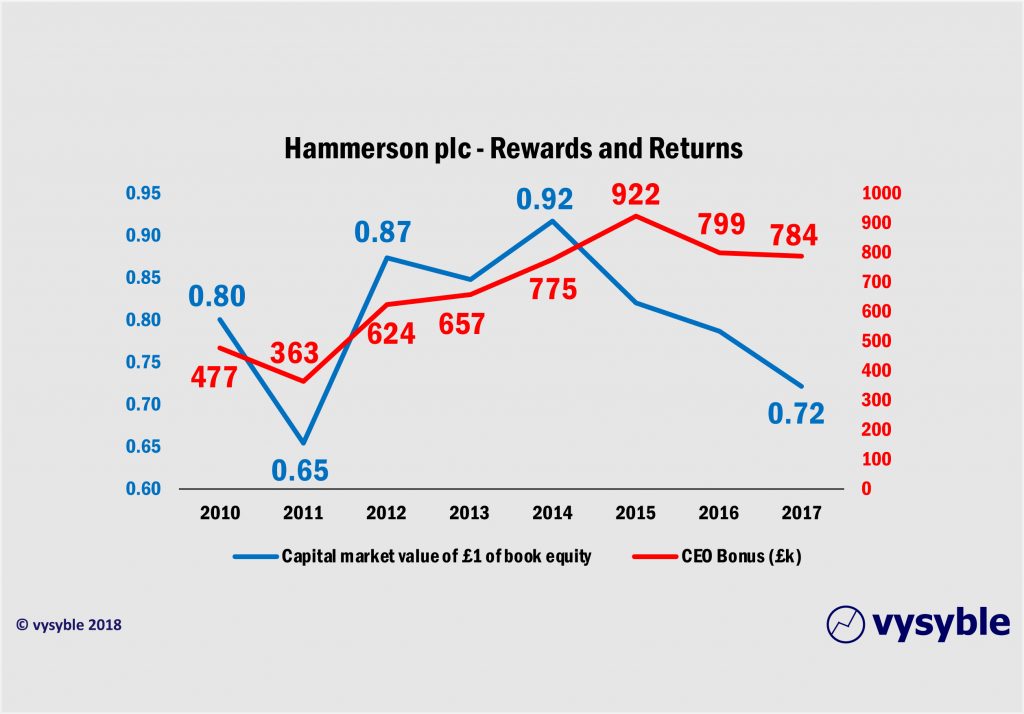

As of 31 Dec 2017, the share price was £5.47, and the market capitalization was £4.34bn but the book equity amounted to just over £6.0bn. In other words, the strategies adopted by the CEO and the top team have resulted in a situation where £1 of book equity was worth 72p on the capital markets.

In fact, the market capitalization between 31 Dec 2016 and the end of 2017 had fallen by just over £200m and yet the CEO was, according to the 2017 Annual Report, awarded a bonus of £784k. Furthermore, bonuses paid to the executive directors in 2017 alone amounted to £2.4m.

When we review the value of £1 of shareholder’s equity for each year going back to 2010, the highest value on the capital markets is 92p at the end of Dec 2014 and the lowest is 65p at the end of December 2011.

Perhaps we have a misguided view of capitalism but if you are quoted company then surely the Directors and the wider Board are obliged to pursue the value-maximising strategy for shareholders. Part of this entails finding and identifying robust answers and solutions to the following questions and challenges:

- Performance objective – a decision relating to what the company will define as success and ideally one that includes ALL of the costs of doing business. Certainly, it should be the lens through which strategic alternatives should be viewed, assessed and chosen.

- Participation questions – deciding where and for how long the company will compete to achieve its performance objective.

- Positioning questions – deciding on how the company will compete to achieve its performance objective.

- Organizational choices – the CEO and the top team need to make decisions that will build an institution that can maintain high performance over time

- Risk Management – deciding how the company will protect its performance from disturbing or catastrophic setback

- People skills – how can the CEO build, motivate and incentivise a team to achieve the performance objective?

The current position for Hammerson cannot be the result of pursuing a value maximizing strategy for shareholders and yet between 2010 and 2017, according to Hammerson’s annual reports, the “bonus” to the CEO totalled £5.4m despite the company consistently producing a capital market value less than book equity.

The company may indeed defend its position with a raft of metrics, measures and debate, which will support the award of the bonuses etc. In fact, the metrics are all laid out within the annual report and there is nothing underhand or secret in that sense.

However, the man on the Clapham omnibus might legitimately argue that the incentives for the senior team would seem to be potentially misaligned with driving the wealth of the shareholder. And furthermore, he might also ask with good reason ‘How would Hammerson’s significant shareholders feel about this?’

vysyble