13th March 2019

In business there is nothing illegal about an owner investing their own money or other resources to expand or improve their going concern. Similarly, there is nothing illegal subject to the satisfaction of creditors and employees about running your operation at a “loss.” Indeed, you are pretty much free to run your business as you see fit as long as you abide by the laws of land. In fact, one might argue that such beliefs underpin a modern, well-functioning, capitalist economy.

Football, however, imposes a slightly different set of rules and regulations, over and above the laws of the land in relation to how the “business side” of the club is managed. Indeed the respective football “authorities” impose limits on the quantum of resource that a club can invest within a given time period. The in-going belief is such an obligation restricts the level of losses that could be incurred, and hence, according to the “rule-book”, preserves the on-going and longer-term health of the club. Almost by default and despite the positive intention of the additional “safeguards” it does nevertheless prevent the owner from running the club within a regime of total control, the logic being that the clubs are in effect, national assets, and therefore need to be protected from the more pernicious practices of modern capitalism.

Such is the basis of UEFA’s “Financial Fair Play (FFP)” scheme, which applies to clubs participating in European competitions. However like any regulatory scheme that imposes restrictions on behaviour but is not integrated into domestic legislation, there is a danger that ways will be found to navigate around the said regime.

To their credit, both the EFL and the Premier League have attempted their own form of Financial Fair Play. However, the key failing in all of these schemes is that they do not take an economic perspective and therefore fail to truly understand the structure of the very industry or marketplace that they are attempting to regulate. The critical aspect is a failure to incorporate the ongoing cost of equity capital i.e. money that is invested by club owners into their club in exchange for additional shares. Nor does it readily consider taxation which as far as we can see does not exist in the world of football until the tax demand threatens the closure of a club.

Of course and largely for reasons constructed at the time of the Industrial Revolution, the accounting view is that equity capital is free – a perfectly legal but ultimately flawed perspective. By contrast, the “Economic” view largely based on the work of the great economist Alfred Marshall but also incorporating the Nobel prize-winning work of Mondigliani and Miller takes a view that value is only created when all of the costs of doing business have been satisfied and are exceeded by revenues.

The associated charges for such capital once calculated, often by using the work of Modigliani and Miller, can be significant and often to the initial consternation of owners/ managers. It is not uncommon for divisions within highly “sophisticated” business that were once thought to be highly “profitable” to in fact be value destroying once a full charge for all of the capital has been incorporated. No doubt many mangers would have made different decisions had they been aware of such charges and the underlying impact on their business at the time.

Within football, FFP in itself has often been cited as a means of preventing ‘arriviste’ owners from disrupting the traditional cabal of European clubs. There is nothing worse than having to spend more money in order to compete when the new kid in town is inflating player wages and transfer fees to gather in the best of talent. Heritage counts for little when confronted with a state-controlled cheque book.

But as we have already outlined, there is nothing illegal from a legislative perspective in implementing such a strategy and that includes the expansion of debt and/or equity capital. Where it does get complicated is if the expansive club is submitting documentation to the sport’s governing body that is then proven to be false. We’ll let the lawyers work through that one.

Ultimately, there is a strong argument that FFP-type schemes protect the game from over-ambitious club owners who could place their clubs in jeopardy through over-spending and by increasing debt to beyond acceptably safe limits. And that’s fine if everyone plays by the rules but also if the rules themselves are appropriate for the operational practices and requirements within the game.

The competitive nature of football is such that owners have and will continue to spend money far beyond safe limits in order to remain competitive, hence crises at Bolton Wanderers, Aston Villa, Sunderland, Portsmouth, Birmingham City, Notts County etc still crop up with alarming regularity. The financial regulations are supposed to prevent this yet transgressions occur frequently – the breach of the 3-yr rolling window limits by teams usually chasing promotion from the Championship being one such example.

And then there is Manchester City, a club playing fine football, winning titles and making inroads into European competition. Indeed, their capital-intensive rise to dominance has been nothing short of astounding but the recent disclosure of documents via Der Spiegel relating to some of the club’s alleged financial dealings cast a dark shadow over the club’s recent successes. With four separate and ongoing enquiries into the club’s operational behaviour, the overall role and effectiveness of the FFP format must be questioned given its apparent inadequacies in dealing with clubs with high ambitions and exceptionally deep pockets.

Therefore, the fundamental question is whether or not the game requires some form of financial regulatory control. In our opinion the answer is a strong YES. Businesses can and do go bust. Business owners can run out of money and make poor decisions. Indeed, we have argued that business owners and shareholders make incorrect decisions because they evaluate their business performance with incomplete and incorrect metrics – you cannot manage what you cannot see!

The risk within football is that the high-spending, deep-pocketed owners will force smaller and more vulnerable clubs out of business. We also have previously highlighted our deep concerns about football’s business model and its over-reliance on media income. So from both sides of the balance sheet, football clubs face ongoing and challenging trading conditions.

The influence of Chelsea’s spending spree from 2005 onwards and the effect of Manchester City’s largesse on the finances of football is very clear. However, the difference of opinion on this performance depends largely on how it is measured.

Let’s take Manchester City as an example.

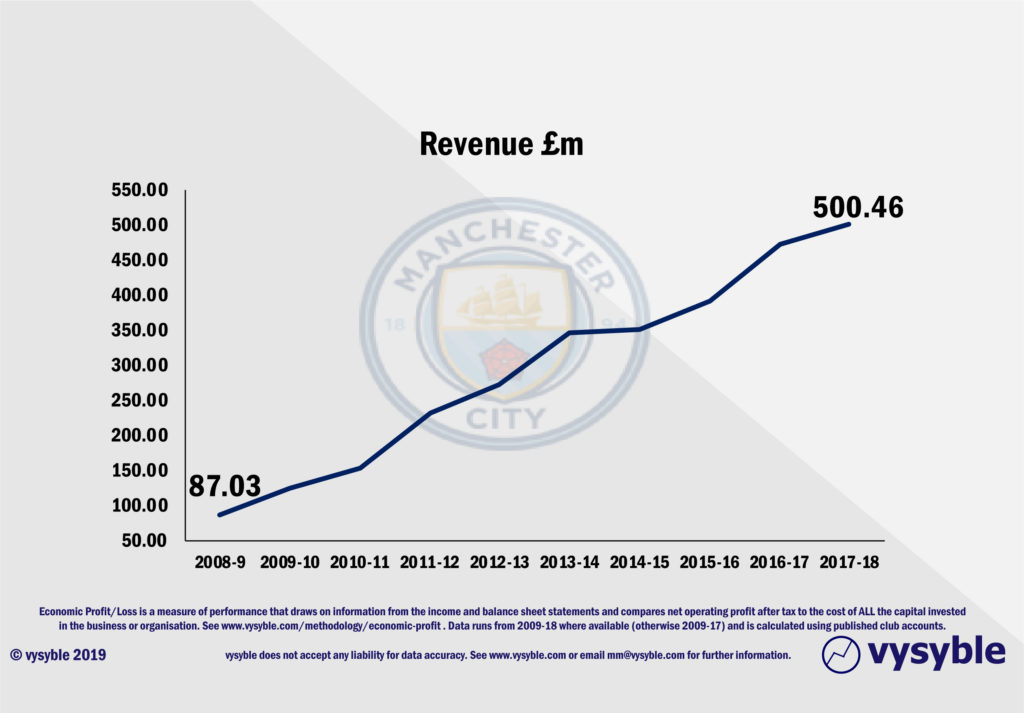

From the 2008-9 season when the UAE acquisition occurred, the club’s revenue profile has been one of impressive growth.

No other club that we have monitored since 2009 and has played Premier League football has such a near-straight line growth profile in revenue performance.

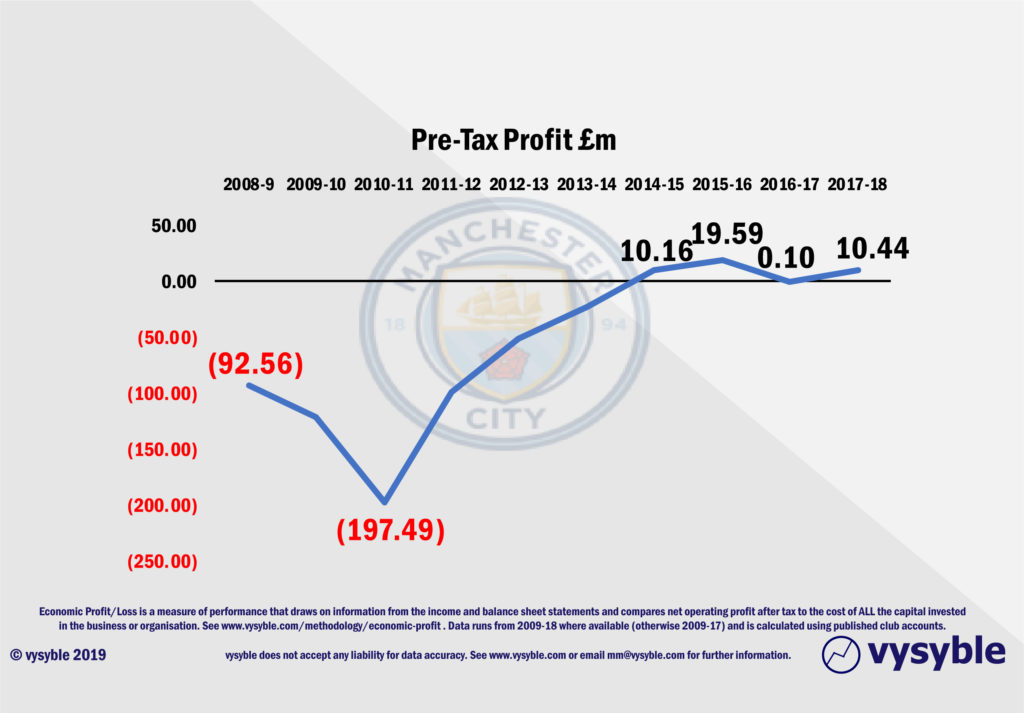

When we consider the Pre-Tax Profit performance of the club, the effect of FFP implementation in 2011-12 is clear to see.

Record club losses of £197.49m in 2010-11 due mainly to the acquisition of players and a significantly larger wage bill have been replaced by Pre-Tax Profits of £10.16m just 4 years later.

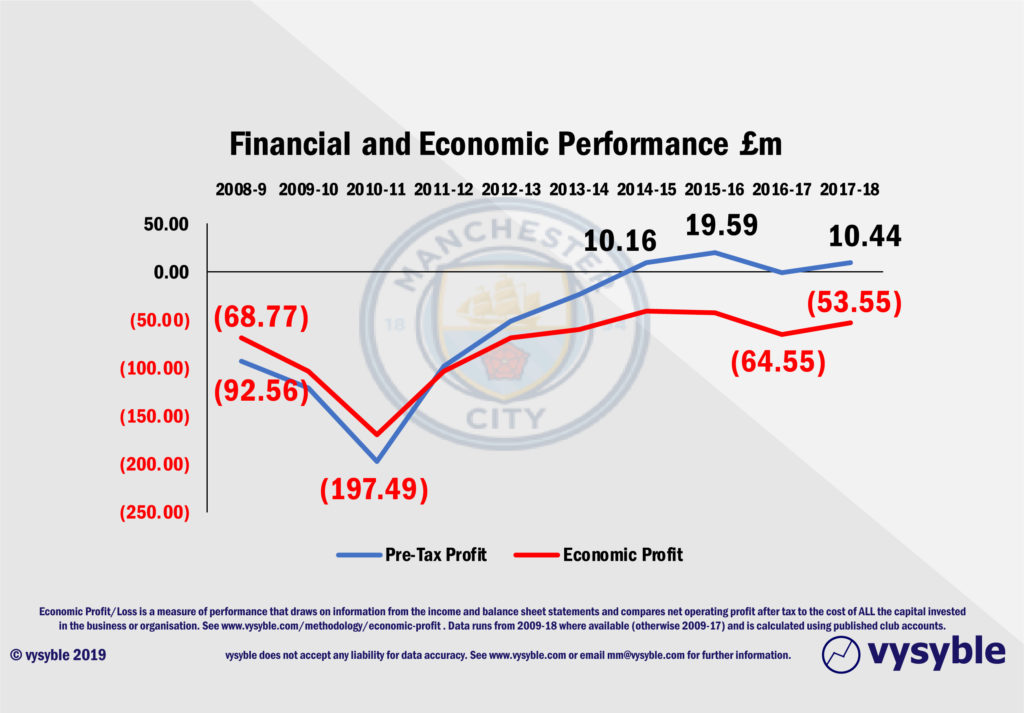

When we factor in taxation but also the cost of the investment by the owners in the form of equity capital ie the Economic Profit calculation, we see a very different picture.

The Economic Losses are substantial yet under FFP rules the club is profitable and operating within limits. In fact, the total Economic Loss for the period 2009-18 for the club is a staggering £775.20m.

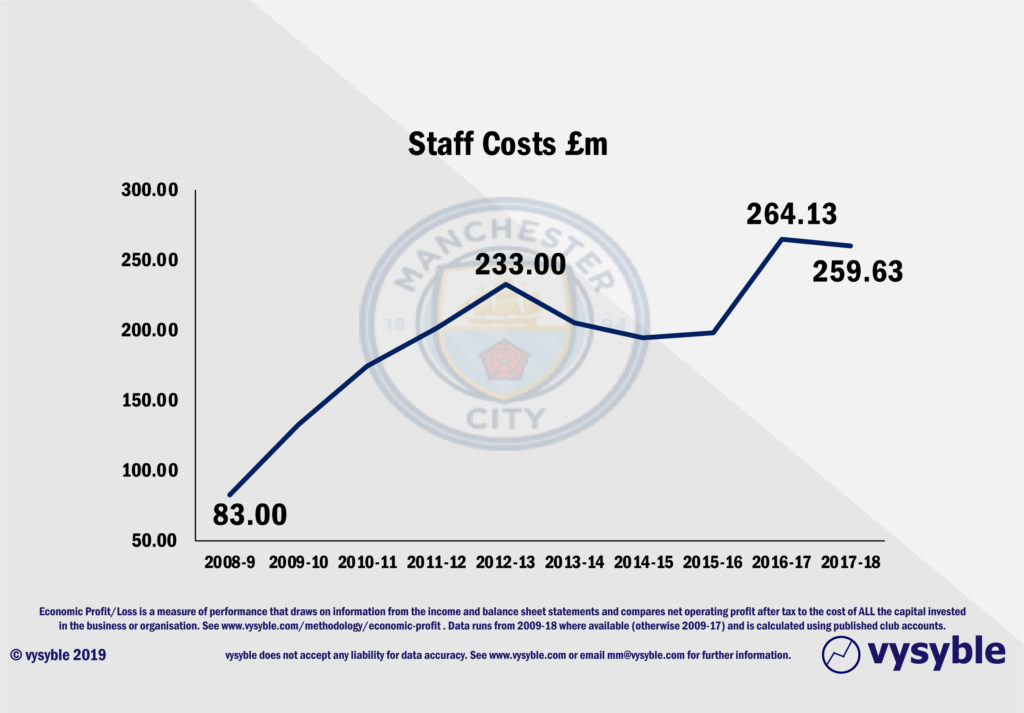

Also note that the City Football Group was formed in 2013 to take the role of the overall controlling entity for Sheik Mansour’s football-related interests including Manchester City. Staff costs for the club fell by £28m at the same time which is unusual for a Premier League club given the consistent increases in revenue. We assume that this is partly due to the transfer of staff and responsibilities to the controlling company, which again is perfectly legal and above board.

However, in our view, the FFP ruleset does not cope well with multi-company structures and does not offer a view in terms of cost transfers and the effect on overall results in such circumstances.

Our overall point is that the fundamental economics of club performance and thus the game are not understood nor are they being measured in any meaningful way. Therefore, the game is making decisions based on incorrect measures and will undoubtedly develop strategies and business directives that are going to be counter-productive as it has clearly done so already given the above and other examples.

So, what is the remedy?

The first step is to use the most transparent and demanding measure of performance ie Economic Profit and Loss. As the example with Manchester City shows, the perspective on performance depends on the depth of the measure. Our own research has highlighted a number of trends and pointers within football’s financial performance over the last 10 years to raise serious concerns upon which we have extensively reported.

The missing ingredient in the current set-up is the lack of any legal obligation to maintain the financial stability of a football club. We argue that the historical, cultural and economic presence that football holds within the fabric of the nation is important enough that the operation of clubs from a certain level upwards should be regulated with an independent Football Regulator who should have sweeping and binding powers in terms of preserving the financial status of the game. We’ve often heard the line that football is a special case so let’s treat it as one.

It is abundantly clear that the current set of rules implemented by the Premier League and the EFL are not appropriate as they either ignore or just cannot “see” the underlying economic performance. In addition, the somewhat inconsistent application of certain rules by the governing bodies to specific financial and operational issues at club level warrants a review.

The issue of owner behaviour is a complicated one. We assume that owners want to see a successful football club but also want to be able to eventually sell without loss or penalty. Don’t forget, clubs last longer than owners so the onus must be on the owners themselves to behave as a custodian of the club. If he/she makes a profit upon sale, then all well and good.

When a prospective owner wants to buy a club, we suggest that he/she signs a legal undertaking with the football regulator to run it on at least an economic break-even basis. A failure to achieve the economic profit break-even position will result in the owner having to relinquish operational control of the club to the regulator. The regulator then manages the financial side of the club back to break-even status and then sells the club on behalf of the original owner giving back the full sale price less the regulator’s costs.

Therefore, if the owner is unable to maintain a minimum break-even position then that owner is deemed unfit to run the club and control is removed. If the owner makes a loss on the subsequent sale of the club by the regulator, then that will be the penalty. The regulator’s interest is not to punish the club but to ensure that the club’s stewardship remains on the right side of the profit line.

Conversely, owners should be allowed to invest in their clubs as their capital input will be incorporated into the overall cost base feeding into the economic profit calculation. Where the owner has to be careful is to manage the capital input and associated charges within the overall economic profit performance of the business to limits set by the regulator. Thus any investment has to be commensurate with the operating performance of the business and a how it uses its overall capital and asset base over and above the current Pre-Tax position.

The most obvious target is to ensure that each and every league club has to reach an economic profit break-even point within an initial target period. This will involve reducing many costs not least of which is staff. Perhaps a period of 5 years from initial implementation – to account for the lengthiest of player contracts – should be allowed for clubs with the specific target of reducing the burden of staff costs to a manageable 50% of revenue.

Transfer fees should be accounted for not on the ability to pay in instalments over the term of the playing contract but on an up-front basis. In turn, this will force clubs to focus more on cash flow and affordability and less on increasing longer-term debt.

It certainly seems to us that the game’s regulatory financial ruleset is becoming increasingly outmoded as the financial dynamics of the game continue to evolve. The lack of consistent application when it comes to owner behaviour and the knock-on effects in terms of ongoing financial performance is one particular concern.

It may indeed take a few radical ideas and some original thinking (we have already approached UEFA with many of the thoughts outlined in this particular blog and elsewhere) to move away from the current position which in turn does nothing to protect the status of some of football’s oldest institutions. Being torn between the demands of global dominance and survival, the game risks being stretched beyond the tolerances of its already delicate financial sinews.

It is ‘the club’ rather than ‘the owner’ which needs to be placed front and centre in any regulatory framework. If all the costs of conducting business were to be considered then no doubt the unfortunate events involving many of the clubs previously mentioned could well have been avoided.

vysyble