12th December 2019

We were delighted to collaborate and support the BBC in its football-related output concerning the current financial state of the game. Regular readers will know that we have covered the financial and economic aspects of football for just over 3 years. Indeed, we released our first report on the vulnerability and reliance of the Premier League’s top clubs on TV money in late 2016. Since then we have consistently challenged the prevailing narrative that all is well within the game – a narrative fostered by a belief that revenue generation in itself is a proxy for economic nirvana.

Sadly, the reality is that all is far from well. Indeed, we believe that the game is in a bit of a state.

What many commentators won’t tell you is that in order to understand the financial dynamics of the Championship and lower leagues, the economic dynamic of the Premier League must be understood first – more particularly the concentration of revenue generation which sits with the ‘Big 6’ clubs of Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur. In 2017-18, this group accounted for 57.5% of the division’s total club revenue.

Commentators will tell you is that the Premier League continues to break revenue records (we expect a combined club revenue total of approx. £5bn for 2018-19, up from £4.83bn in 2017-18) and that ‘profitable performance and strengthening balance sheets, that looked so impossible a decade ago, are now the norm.’[1]

Unfortunately, this does not apply if your club is sitting outside of the ‘Big 6’ group. For instance

- Just five of the remaining 14 clubs recorded successive pre-tax profits between 2016-18.

- In 2017-18, 89% of the Premier League clubs’ pre-tax profits were generated by the Big 6 clubs.

- Eight of the 14 remaining clubs had staff cost totals in excess of UEFA’s safe guideline of 70% of revenue.

Arguably, the Big 6, as we indicated in our last edition of ‘We’re So Rich It’s Unbelievable!’, are turning the financial screw on the remaining 14 clubs with additional monies from European competition and an increased share of international broadcast rights. It is no surprise to us that this group has occupied the top 6 final positions in the Premier League in 4 of the last 5 seasons.

Indeed, Deloitte’s apparent confidence in the football’s financial model is such that it actively encourages investment into the game with statements such as ..”with no football league clubs entering insolvency proceedings for over five years and our consistent reporting of improved financial stability and profitability for that period, we hope that the developing financial maturity of the football industry will soon be more widely recognised”’[2]

Really? Try telling that to fans of insolvent Bury FC, or indeed to fans of Bolton Wanderers, Macclesfield Town, Oldham Athletic and other clubs where acute financial difficulties have made the headlines in recent months.

The above statements were published in 2018. In the following year, we noticed that Deloitte’s tone had changed:

‘Beyond the riches of the Premier League, it was a year of records in the Championship, most unenviable, as despite record revenue, record wage levels (in excess of revenue) resulted in record operating losses.’[3]

A man on a Clapham Omnibus might wonder what happened to that developing financial maturity? Indeed, Deloitte lets the cat out of the bag with the following line from the same report;

‘The majority of clubs in League 1 and League 2 continue to be supported by owner contributions.’[4]

So ‘improved financial stability and profitability’ only works if owners keep dipping into their pockets? To us that is a very interesting perspective and we leave you to draw your own conclusions…

We argue that it is extremely rare for the economic and financial dynamics to shift from being positive to dire in such a short period of time – unless something catastrophic has occurred. Usually, and we have seen this in our work on Carillion, Tesco and many other enterprises, the underlying disruptive and value-destroying factors and behaviours will have been in place for some time.

The increased levels of transparency achieved by the economic profit measure, especially in applying a cost to equity capital (which is one of the more common methods used by owners when investing in/shoring up their football clubs whereby money is exchanged for a further issue of shares), has enabled us to see and report on much of the turmoil that has only recently manifested itself in the traditional format of the balance sheet/accounts statements and well ahead of time.

Our widely-reported interactions with the EFL in 2017 resulted from our analysis of those clubs being promoted from and relegated into the Championship stretching back to the 2008-9 season. Just to be clear, there has only been one instance of a club promoted into the Premier League with an economic profit since 2009 (Crystal Palace in 2012-13) during this period. Relegated clubs carry a bigger risk of financial stress not least as a result of the reduced media income which is partly tempered by the Parachute Payment scheme.

Sometimes the dual and conflicting ambition of promotion and balance sheet repair following a bruising and failed Premier League survival effort can result in further relegation into League One (Sunderland, Wigan Athletic, Wolves) and additional financial stress. Our economic profit data was explicitly clear in highlighting unsustainable situations and impending club failures.

Unfortunately, and sadly, the EFL failed to recognise this. Its complacency in referencing the lack of club insolvencies as a glowing measure of the success of its financial regulations was to us, having seen the economic data, astonishing.

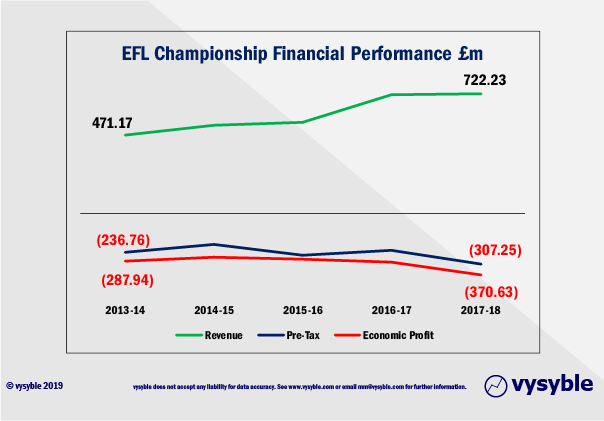

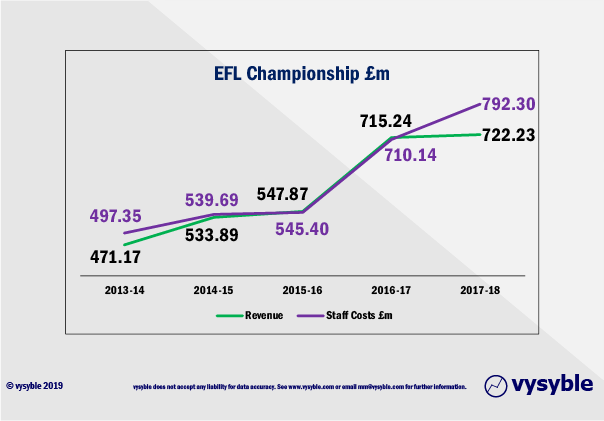

As the chart below illustrates, the Championship has been in

poor financial shape for some time.

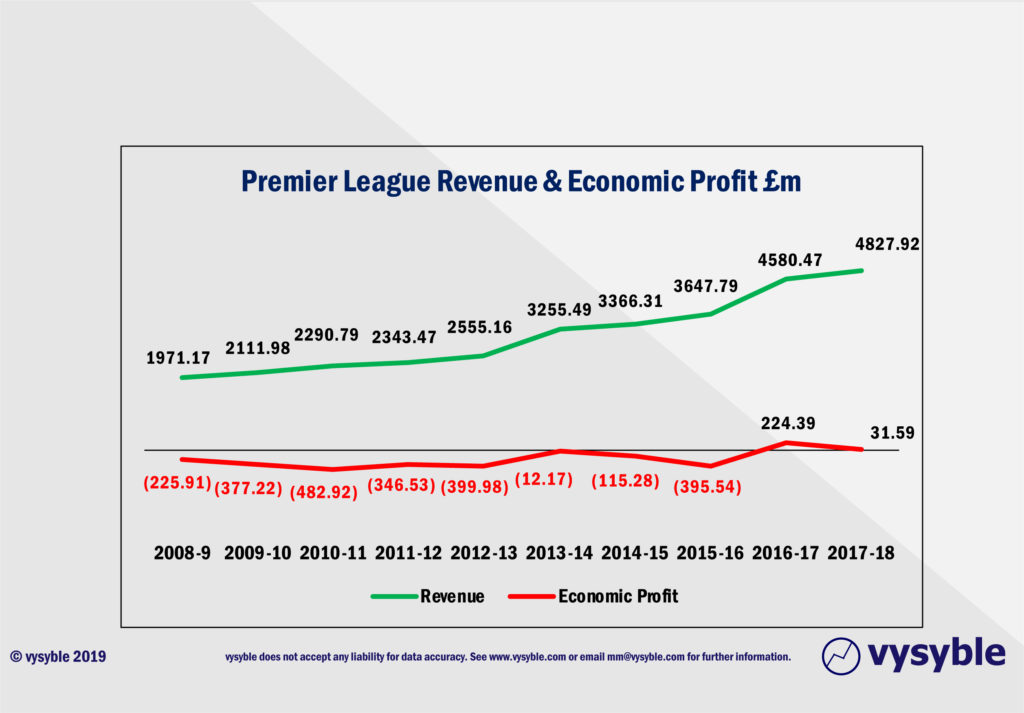

The lure of Premier League riches would appear to be an obvious

dynamic but the narrative of the largest revenue-generating league in the

world [1]

hides a mix of economic losses and short-lived tenures. Indeed, the Premier

League has only achieved two economic profits in the last ten years.

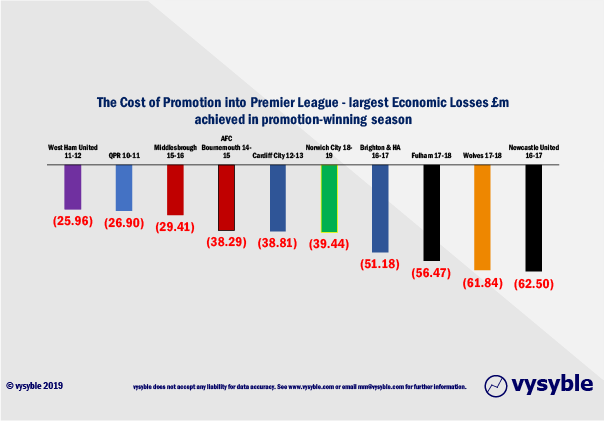

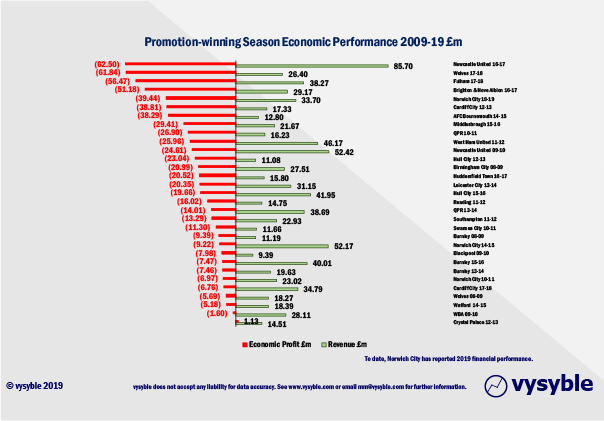

Rather like Icarus rising towards the sun, chasing the Premier League dream can be a very dangerous (and costly) pursuit. We said so in 2017[6]. The ‘cost of entry’ to the Premier League in economic profit terms has increased significantly since the bumper TV deal of 2016-19.

Our analysis shows that one-third of promoted clubs will be relegated from the Premier League following a single season with two-thirds relegated after three Premier League seasons.

When these losses are compared with the revenue earned, the burden of ambition is clear.

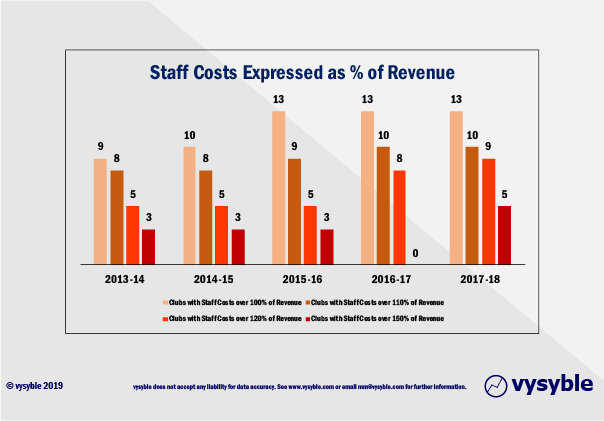

The key driver is staff costs which tends to exceed revenue levels.

Indeed, there are worrying and developing trends that suggest the Championship staff costs/revenue ratio is going to get worse over time.

What is not helping this situation is that Premier League staff costs have experienced annual double-digit inflation since 2015. This in turn has helped to inflate labour costs further down the football pyramid. Also, 2017-18 was the busiest year for Premier League transfers with £2.9bn of talent traded in and out of clubs. All this helped to feed a 13.37% increase in Premier League staff costs, the highest % increase since 2011.

Whilst it would be easy to compare directly with the Championship staff cost increase, the data is unfortunately skewed by Newcastle United’s huge £112m staff cost in 2016-17 as the club spent its way back into the Premier League. The next highest Championship club staff cost is Aston Villa’s £73.11m in 2017-18 which was more than likely a major factor in taking the club to the brink of administration.

Even with the EFL’s new media deal with Sky which started this season (2019-20), the situation is unlikely to improve. The 5-yr deal pays £595m or £119m per year to broadcast 138 league matches per season plus Carabao Cup games. To put this deal into perspective, the Premier League received £670m for a 4-yr agreement back in 1997. The new arrangement is a 35% increase on the previous iteration but broadcast revenues without parachute payments are generally dwarfed in percentage share terms of overall club revenue by the matchday take.

Recently, there has been much controversy surrounding the sale and leaseback of stadia to club owner companies. This is not illegal as the laws of the land currently have it. In the corporate world, the use of sale and leaseback deals to free up funds tied to assets such as offices or land is very common indeed.

Curiously, the EFL rules did indeed prevent such deals from taking place as a means of contributing to a club’s EFL Profit & Sustainability (P&S) obligations. However, the rules were quietly amended in 2016. As a result, Derby County, Reading and Sheffield Wednesday have since executed such transactions with the effect of vastly reducing losses within the club limited company whilst raising staff costs to near-parity with those clubs that currently benefit from parachute payments. All above board apparently but not without rancour from other clubs and lately in Sheffield Wednesday’s case, the EFL itself.

Of course, the liability of rent will be transferred to the balance sheet and we remain curious as to what the relevant ‘market’ rents turn out to be on a case by case basis.

By its very nature, the Championship is a dynamic division with 6 clubs exiting every season as a result of promotion and relegation from the pool of 24. Indeed, just 7 clubs have been continuously plying their trade in the Championship between 2014-18. And they are: Birmingham City, Derby County, Ipswich Town, Leeds United, Nottingham Forest, Reading and Sheffield Wednesday.

Notably, three of the seven clubs have executed sale/leaseback deals on their stadia (see above). Additionally, Birmingham City fell foul of the EFL’s financial regulations and received a points reduction penalty last season as a result. The predominant lack of parachute payments (Reading did receive payments up to 2017) would seem to have prompted some creative thinking.

However, the numbers do not lie. The combined revenue for the seven clubs rose from £146m to £171m (17.21%) yet staff costs rose from £146m to £241m (64%) between 2014-2018. Economic Losses remained static at -£84m for both 2014 and 2018, tempered by the stadia sales with a combined sale price of £166.5m (Derby County £80m, Reading £26.5m and Sheffield Wednesday £60m).

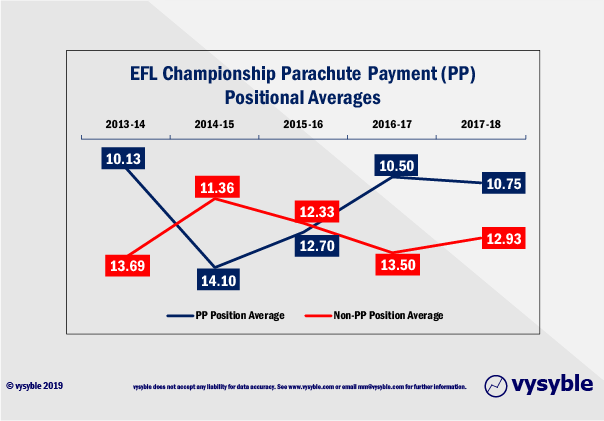

In the 27 instances of relegation back into the Championship since 2009 where accounts are available, there were 24 instances of economic losses in that first Championship season despite parachute payments. That is not to say that the parachute payment scheme does not influence performance on and off the pitch (see above).

Over the most recent five years of accounts, Championship clubs in receipt of parachute payments have performed marginally better than those without but on an average basis the margin between the two is not so great.

In terms of promotion, 8 out of the last 15 instances were achieved by clubs that were in receipt of a parachute payment.

To conclude, with football being what it is, chasing the dream is what clubs and their owners do and are expected to do by the fans. Unfortunately, the result is a growing cohort of clubs with significant and increasing cumulative losses, where the cost of labour is rising faster than revenue. Even the realisation of this ambition can be fraught with danger and difficulty.

Looking ahead, the Premier League Big 6 clubs will continue to work behind the scenes for financial advantage. The prospect of a European Super League in 2024 is palpable and will present English football with its most radical operational challenge. On current evidence, the EFL is ill-equipped to cope.

Unless the relevant government departments, regulators and administrators of the game recognise the true economic and operational picture, we are certain that football will end up in a dark, dark place.

[1] Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2018

[2] Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2018

[3] Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2019

[4] Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2019

[5] Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2019

[6] Over The Line 2017. Published by Vysyble.

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter