4th December 2017

If you take a quick look at our ‘in the news’ page, you will see many recent additions to our growing list of media exposure surrounding the weekend’s outstanding English Premier League fixture (Arsenal vs. Manchester United) and its status as the first billion pound game in English football.

As interest in the story went global (Australia, the Far East, Middle East, Europe, the UK and beyond), the fact remains that the Premier League and its representative agencies were nowhere to be seen. One might have thought that such a momentous point in the English game’s history would have been noted, if not highly publicised, as another example of success in the seemingly unstoppable growth in Premier League club revenues.

Indeed, as we worked through our media commitments during the week leading up to the game, we were expecting to be usurped by what has been a very efficient and effective PR and marketing function for football’s upper tier. What surprised us was the roaring silence and lack of activity.

Historically, the Premier League’s principal success criterion has been the level of revenue, – something that is frequently repeated across the football world. Indeed the annual report on Premier League clubs conducted by a certain firm of accountants inevitably waxes lyrical about the health of the game based on revenue growth, the increasing value of TV rights etc. The record never really changes as the numbers get bigger every year. However, as we continue to point out, examining the iceberg above the surface but ignoring the depths beneath the waves hides a multitude of truths, and so it is for football.

For the two clubs with combined annual revenues of just over £1bn, the fixture hid a number of potentially worrying economic trends. Both clubs have incurred economic (where all the charges of conducting business are taken into account including a charge for capital – see methodology) losses in each of the last four years with only one achieving an economic profit in the last seven years – Man. Utd in 2013.

The two clubs have accumulated revenues of £5.14bn since 2011 and yet have managed to generate accumulated economic losses of £240m over the same period, of which £154.51m resides in North London.

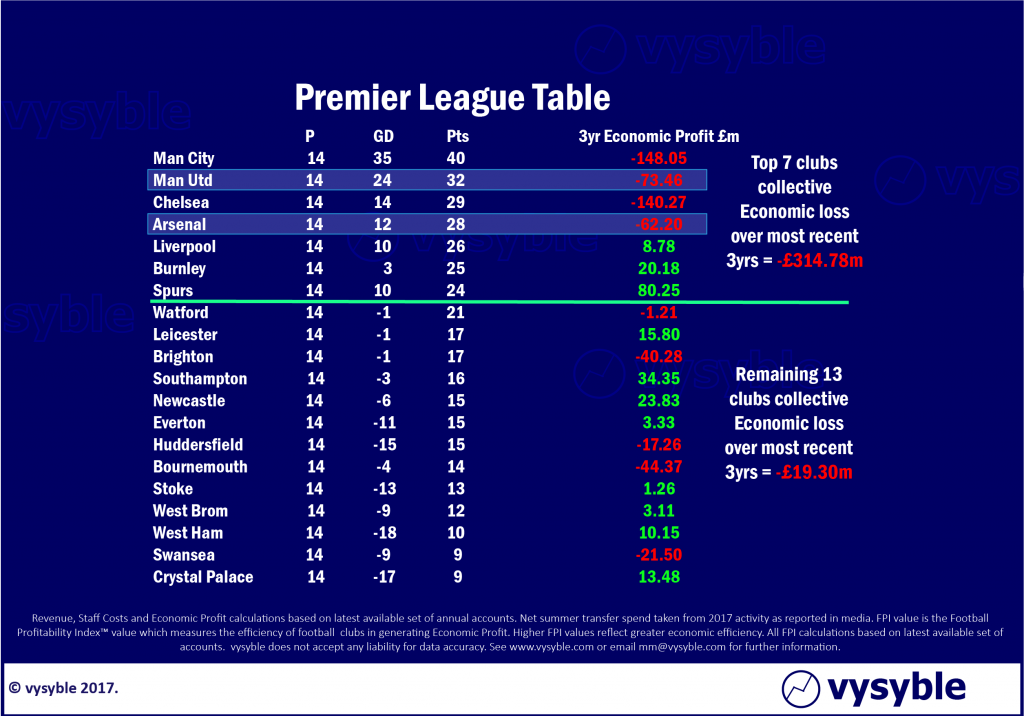

The Premier League table on the morning of 2nd December highlighted the general advantage that the high-revenue, free-spending and low economic return-generating clubs have over their more-financially prudent adversaries. It pays to have a generous benefactor, but the destruction of value is still eye-watering.

Recently, the fixture lists have thrown up some real gems from an economic perspective. In the EFL, we had the ‘Game of Woes’ on 18th November 2017 whereby the two most economically-challenged former Premier League clubs (QPR and Aston Villa) took part in a Championship game with combined economic losses of £311m over the most recent 5-yr period. This serves as a good example of the downside of top-flight football where ambition has stretched beyond financial and economic sensibility. Despite the presence of ‘generous benefactors’, both clubs have ended up in severe financial and economic difficulty with QPR incurring a £40m fine from the EFL as a direct result of its financial behaviour.

Next weekend we have the “Manchester Derby” game which is the most valuable game in the Premier League to-date when viewed on a combined club revenue basis (£1.054bn, although Man City’s revenue of £473.4m is over a 13-month period). If you think Arsenal’s economic track record is poor, then look out for our Matchday Metrics service to find out just how far and away Manchester City’s economic performance has been relative to the rest of the clubs in the division. In this case, it helps to have a state-backed ‘generous benefactor’.

So, what are we to make of the senior division’s “administrative silence” regarding the first billion pound game? Perhaps it has come around to our way of thinking and has realised that it is not just about the revenue? Or it may be the case that combining club revenue numbers is an ‘irrelevance’. If so, have we seen the last of annual revenue ranking tables and reports? Will the combined annual revenue number for the Premier League (which we think will be about £4.38bn for 2017 – up from £3.61bn last year) for the division be consigned to oblivion? Probably not.

One thing is certain – we’ll be ready once again for the most valuable game in the fixture list next weekend.

vysyble