The recent debacle involving Thomas Cook has caused heartbreak and chaos for many people, not least the rank and file employees of the business. It has also cost the UK taxpayer of the order of £520m with no doubt further costs to come in terms of welfare benefits for former employees and further losses down the company’s supply chain.

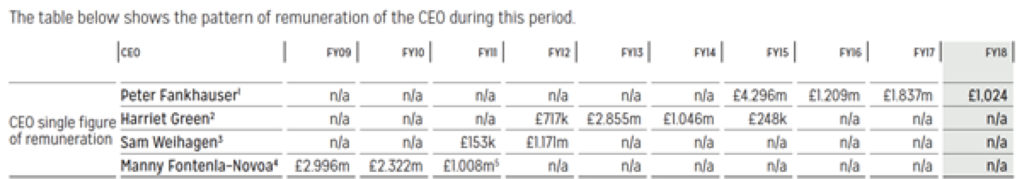

Apparently, our MP’s are launching an enquiry into “corporate greed” at the company, not the least of this the fact that the last 4 CEOs ‘earned’ a total of almost £21m since 2009. Additionally, the company’s auditors – EY – are going to be put under the spotlight too, which is to be applauded.

But what about the Chairman and the non-Executive Directors? This shocking collapse took place under their governance.

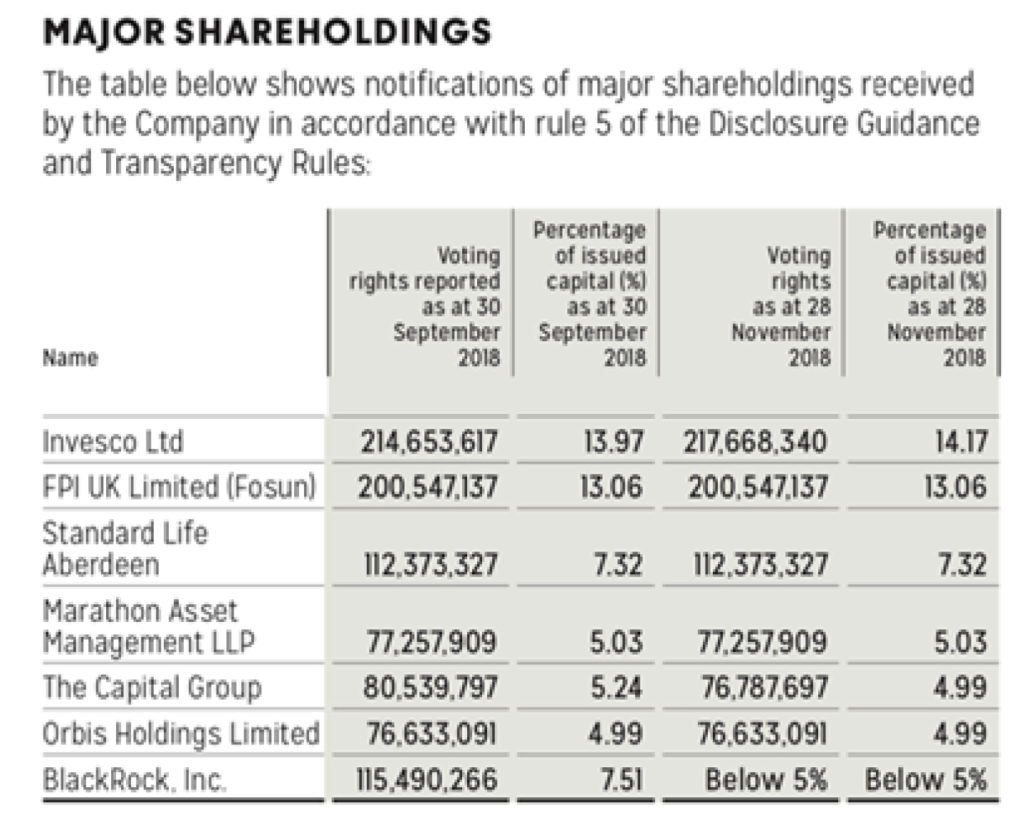

What about the large fund managers and investors such as Invesco, Standard Life Aberdeen, Marathon, Capital Group, Orbis, and BlackRock? Why did they put your hard-earned money and mine into Thomas Cook?

As usual, much of the analysis and commentary from the so-called business media has been both superficial and unhelpful.

So why did Thomas Cook collapse?

Detailed analysis shows that:

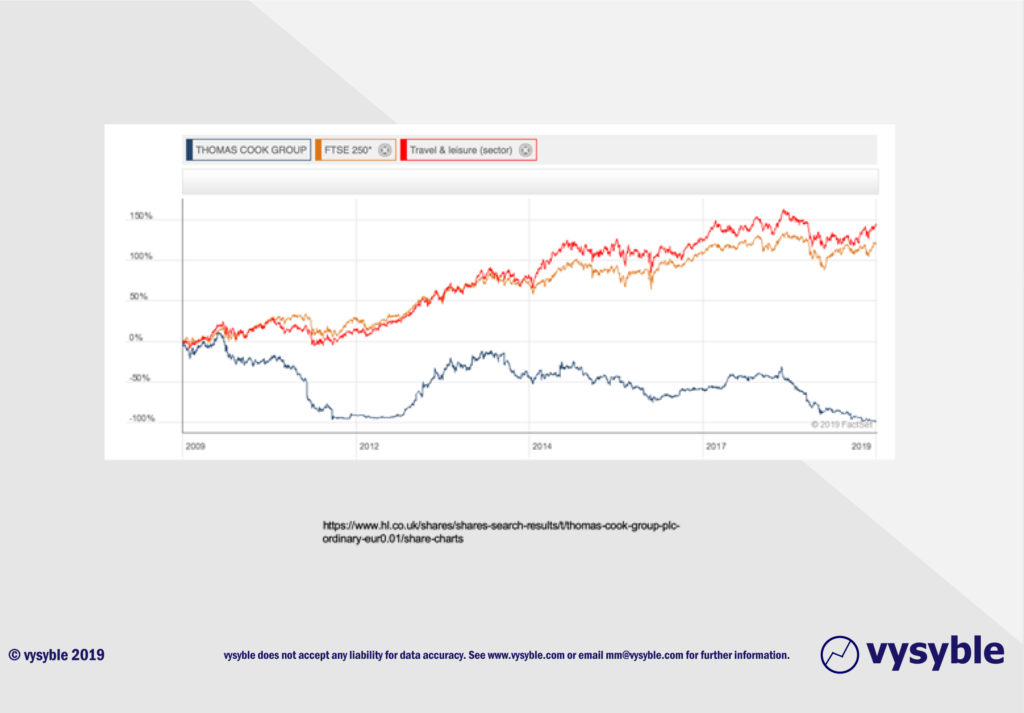

- Thomas Cook has been a poorly performing investment for years. It massively underperformed both the FTSE 250 and the Travel and Leisure sector at least since 2009. Nothing new there, then.

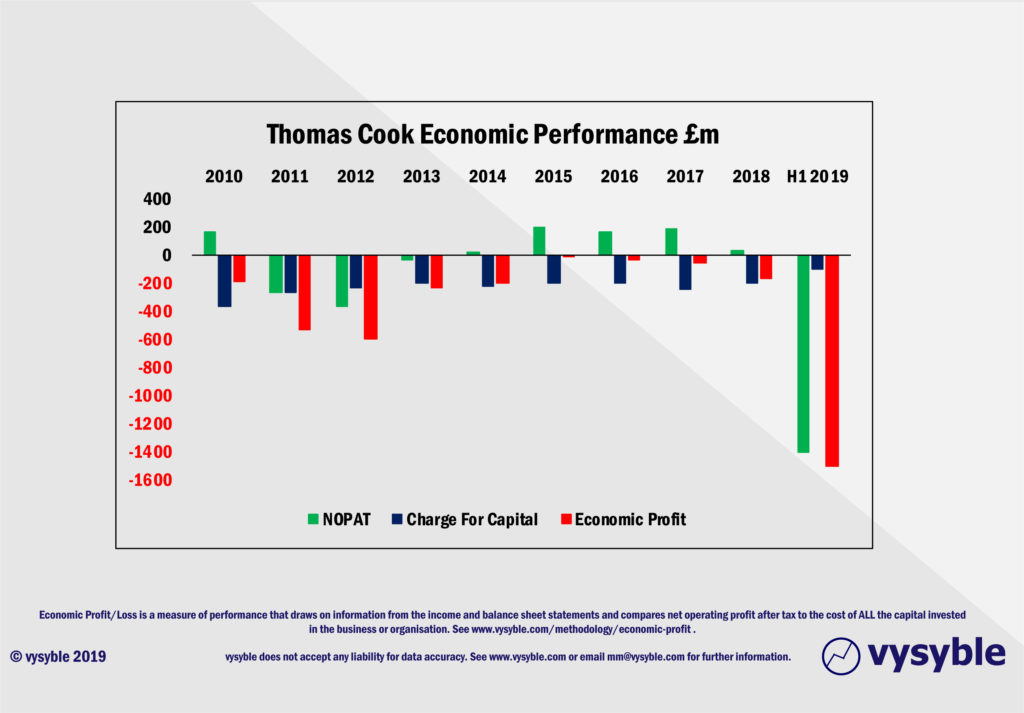

- This shocking performance should have been visible to the Board – and everyone else – because the company had not generated a positive return on capital in any year since 2010. The inevitable collapse should have been evident for some considerable time…

- And yet the Board were happy to highly reward this “profoundly challenged” management team throughout this period as they burned shareholders money – £3.6bn in economic losses since 2010.

- And major (and so-called ‘expert’) fund managers and investors held large positions in the business.

A succession of Thomas Cook CEOs have pursued strategies misaligned with driving the value of the business. The company’s reports reveal their fundamental errors as:

- Using the wrong objectives for the business. They appear obsessed by growing revenue instead of driving value.

- They used the wrong financial metrics to monitor and manage the business. They used deeply flawed accounting measures such as EPS and EBIT rather than economic measures that include all of the costs of the capital within the business.

- Minimal or no understanding of what drives value on the capital markets and hence strategies fundamentally misaligned with value creation. Their strategies were clearly inferior to those adopted elsewhere in their sector… and yet they ploughed on.

- Their purchase of MyTravel in 2007 was obviously a foolish and misguided idea even then.

- Their incentive reward schemes were ill-thought and probably actively encouraged them to do things that destroyed value for shareholders.

It is tempting, as Paul Williams has done so, to see the collapse of Thomas Cook through the dominant political lens of our time – Brexit (Thomas Cook: The Brexit bankruptcy – Prospect Magazine 27th Sept 2019). In addition, other commentators have put forward the collapse of sterling since 2016, the great summer weather of 2018 and the rise of internet travel as factors contributing to the Thomas Cook demise.

For the Brexit bankruptcy hypothesis to be true, both the significant and consistent economic losses stretching as far back as 2010 and the terrible performance, again over time, on the capital markets would have to be deemed irrelevant. Such a perspective is just nonsense.

Similarly, other external factors have some relevance but it is difficult to believe that they are sufficiently conclusive; there were after all, 150,000 customers “stranded” when the company collapsed – a significant number by anybody’s standards and hardly evidence of massive disintermediation via the internet.

In effect, now that the company has gone there is one mass market travel operator left – TUI AG. Given this development, one might rationally expect TUI to exploit its dominant market position and accordingly we expect to see prices within this market to rise – particularly over the short to medium term.

So, back to the questions:

- How can the Chairman and the Non-Executive Directors be held accountable for their outrageous performance?

- What were the major fund managers thinking of when they put your money and mine into the business?

- Will the forthcoming review of the business be wide enough to address all of the issues outlined above (and others)?