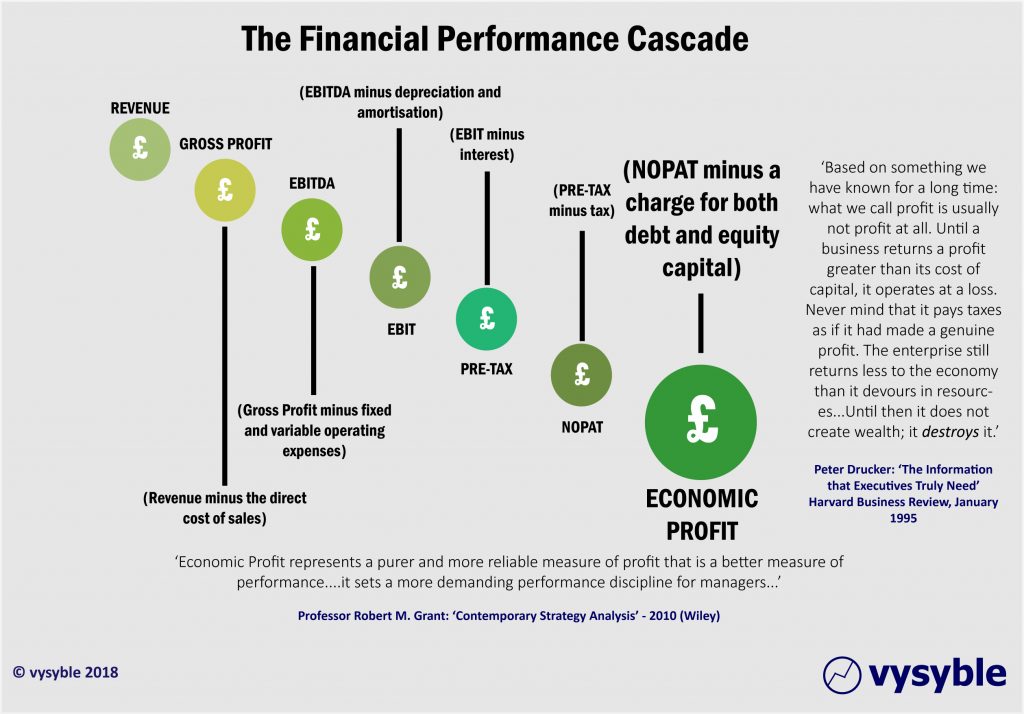

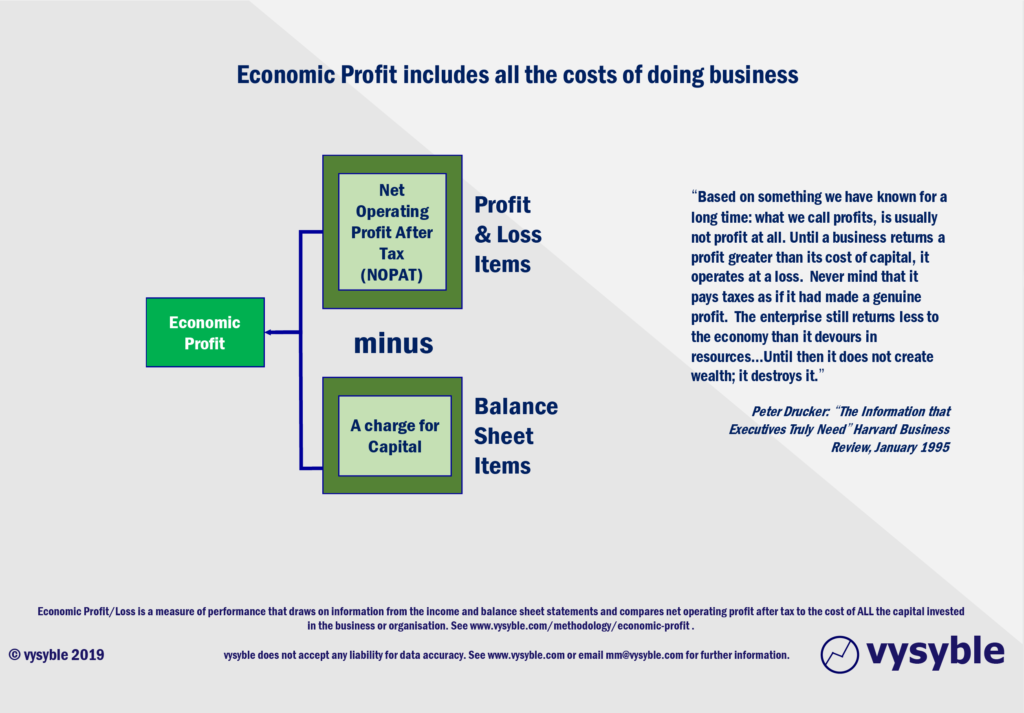

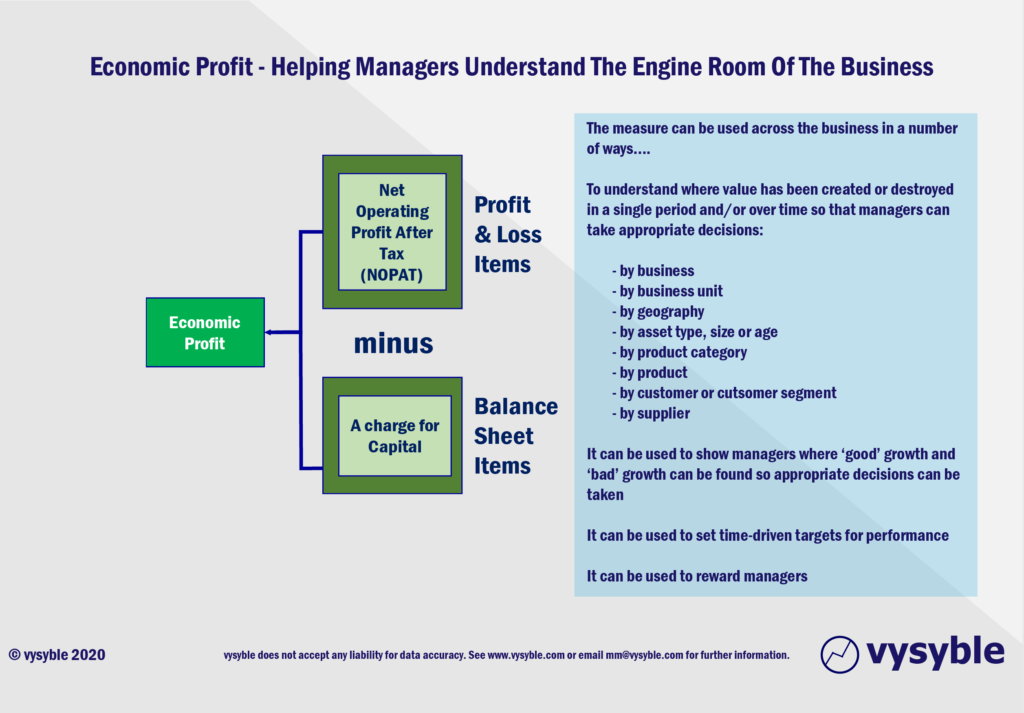

Economic Profit (EP) is a measure of performance that draws on information from the income and balance sheet statements and compares net operating profit after tax to the cost of ALL the capital invested in the business or organisation.

The Economic Profit formula is usually expressed as:

EP = NOPAT (Net Operating Profits after Tax) – (Capital Invested x Weighted Average Cost of Capital)

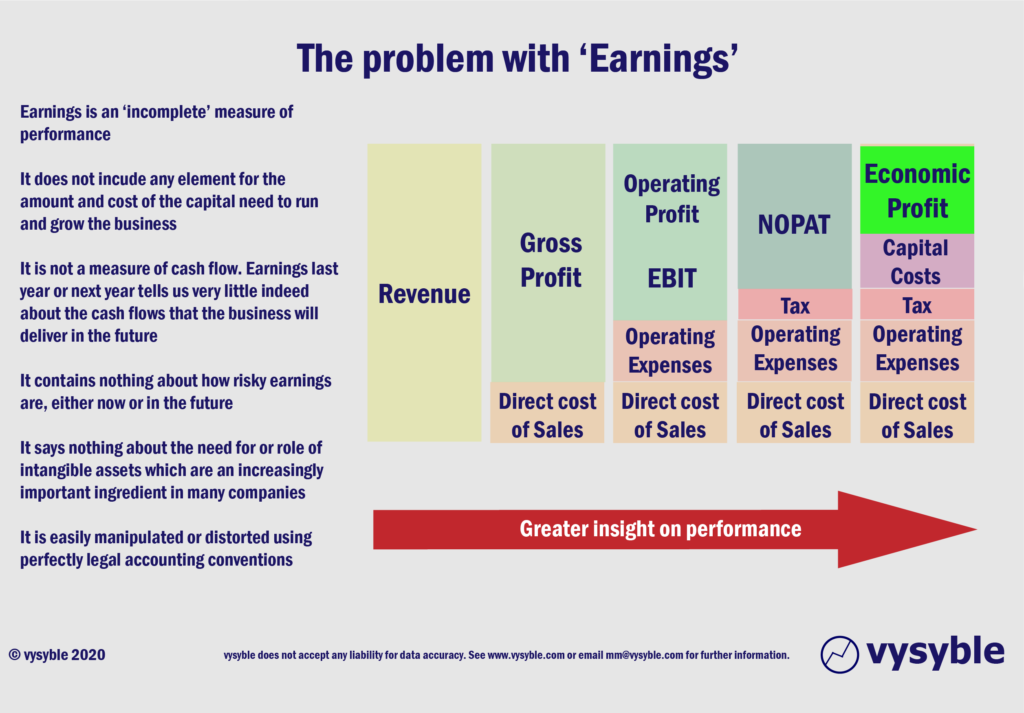

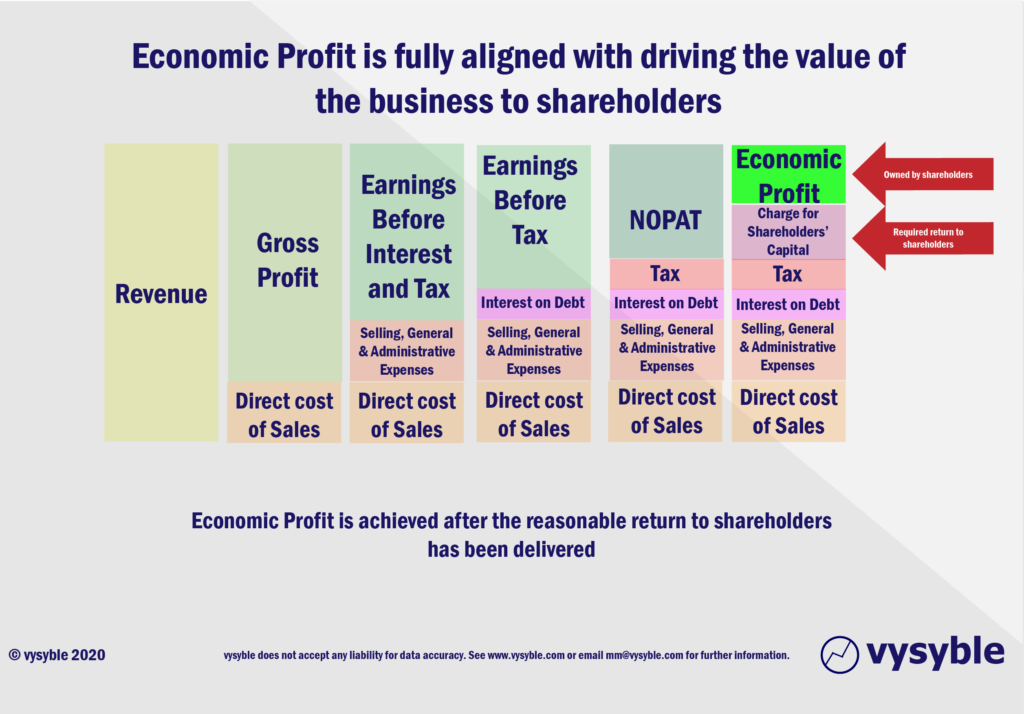

When companies announce their earnings or results, financial analysts usually focus on revenue, EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) and EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax) for a ‘Pre-Tax’ view and perhaps Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT) for a ‘Post-Tax’ view.

We endeavour to calculate Economic Profit (EP). This is the last available step in the financial performance measurement cascade (see illustration below) and provides maximum clarity in terms of business performance.

The Economic Profit measure can be developed further in order to establish the efficiency of the business in creating value. This is the EP/R Value® where the relationship between revenue and EP achievement is expressed in a single number. The ability to compare on a like-for-like basis enables the provision of indices and comparison tables.

Movement in the EP/R Value measure thus enables comparisons to be made between companies, sectors and industries in terms of their relative efficiencies/deficiencies in generating EP.

An example of this capability is the vysyble Football Profitability Index™ (FPI) which tabulates the EP/R (also known as FPI) values for each of the English Premier League and EFL Championship clubs. The individual index values are rebased to 100 so an easy-to-reference comparative between revenue and EP performance can be made based on, for example, a £100 revenue multiple.

So how does all of this work in the real world? Please read on…

Beware of False Profits!

In much of our client consultancy work, typically reporting to the CEO or the Senior Team, we are both tasked with and interested in finding the best way forward for a business / organisation to maximise value creation.

Although one organisation might be more complex than the other, there are a number of common principles and entry points to our work. Sometimes there is an urgent economic imperative, or a perceived performance issue against the marketplace or indeed pressure from investors whilst there may also be an almost intuitive belief driven by the CEO or the Chairperson that the “strategy,” is either not delivering or is in dire need of an update.

Whilst none of the work is “off the peg,” there are a number of questions which we employ that help us to begin the process of assembling a deductive fact-base from which we draw insights and ultimately generate alternatives for consideration and discussion with the CEO and his/her team.

Initial questions might focus on the following:

- What is the value of the current strategy?

- What is the value of alternative strategies?

- How attractive are the markets in which we are active and how do we think about that?

- How would likely changes in market characteristics or industry structure alter industry attractiveness?

- What resources and capabilities are critical for creating value in the industry today and in a changed future environment?

- What is the company’s relative competitive position and how do we think about it relative to competitors and the industry?

- What appear to be the relative strengths and weaknesses of the competitors in the relevant industry segment?

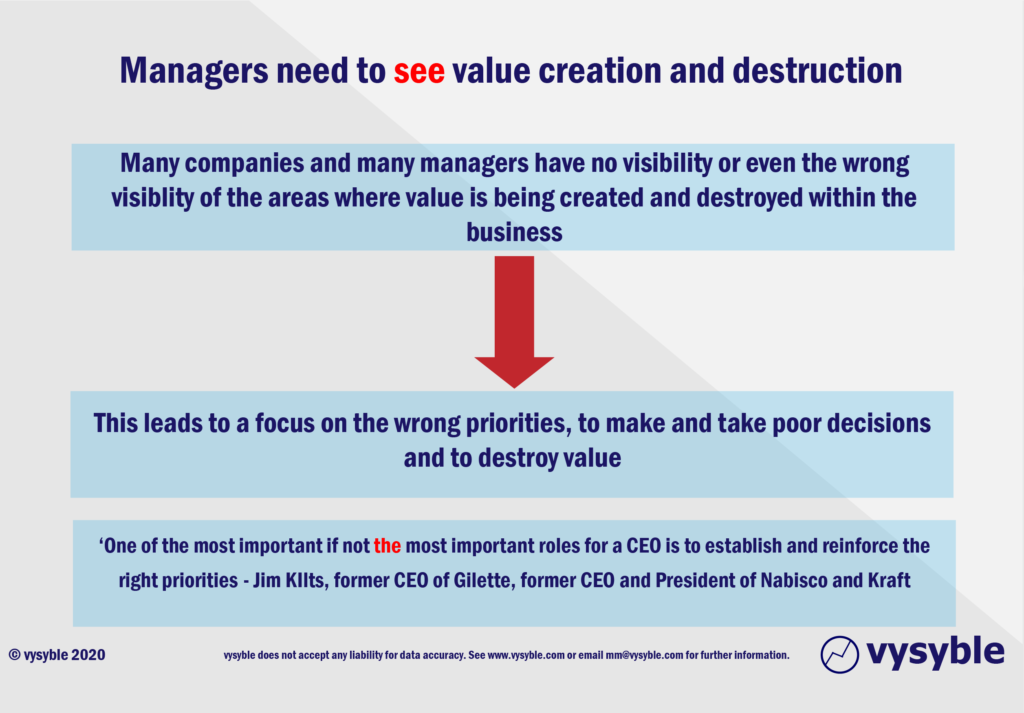

- Is there sufficient strategic and financial visibility of where value is created and destroyed across the organisation?

- How well will a competitor be able to pursue its apparent strategy given its current competitive position, cost structure and available funding?

- What is the performance implied by the current share price?

A keen reader will no doubt notice that we consistently refer to “value,” rather than the more commonly used “profit”. The following paragraphs explain why.

Accounting Profit vs an Economic Perspective

A quote from Alfred Marshall’s ground-breaking book “Principles of Economics”.

“Value is created by investing capital and generating a return greater than the cost of that capital”

Published in 1890, it is such a deceptively simple statement and yet it is difficult to overstate its importance in modern value-based strategic thinking. In fact, when investors and markets lose sight of or are simply unaware of Marshall’s “navigation principle,” the results have usually been catastrophic for stakeholders in the broadest sense along with the wider economy.

Frequently, financial downfalls are usually preceded by talk of “new paradigms”. We believe that the following collapses would not have happened or would have been significantly less severe had investors and the capital markets not lost sight of Marshall’s Victorian-era guiding principle:

Enron was at the time the biggest corporate collapse in history. By its own admission and as its annual report clearly stated, “We have a laser focus on earnings per share”. Earnings per share, or EPS as it is commonly referred to, is a metric which can so easily give the wrong signal regarding value creation and destruction. Therefore, it is highly likely that the Enron senior management team was allocating capital to activities and areas of the businesses which, when all of the costs of doing business were included, were destroying value rather than creating it. The management team were simply unaware of the true fundamental economics of the business – a phenomenon common to more companies than is often acknowledged or recognised.

Here is a simple question. Would you adopt the same business strategy looking at the left-hand graphic, which shows increasing levels of value destruction (and which meets Marshall’s definition), and then at the right-hand “accounting” view which shows a misguided (and incomplete) picture of value accretion?

We think not. Unfortunately, this is increasingly the picture we see when researching many companies in many industry sectors including the economics of the nation’s football clubs.

The dotcom or perhaps more accurately the ‘dot gone’ boom and bust between 2000-2003 was undoubtedly preceded by investor “exuberance” and a temporary “memory loss” regarding Marshall’s maxim. Caution over value creation was sacrificed to the altar of getting big as quickly as possible without creating an effective value-enhancing business model. At the time, much of this activity was fortified by a belief that the internet was the new frontier both in terms of opportunity but also in terms of the measurement of financial performance. Profits did not matter but ‘growth’ did. A fatal combination which is really a way of trying to ignore the overwhelming pull of economic gravity.

In the mid-2000s, the banking crisis arguably originated when management teams lost sight of the value creation principle. US banks lent money to home-buyers and speculators at highly competitive “introductory” rates underpinned by the all-embracing but ultimately wrong assumption that the value of housing stock could only rise. In turn, the banks assembled these “high-risk” investments into packages or ‘longer-term securities’ and sold them to investors who often used short-term funding to make the purchases. Subsequently, when the home-buyer could not afford the mortgage repayments, the value of many homes reduced to lower than that of the original loan. When all of these ingredients reached “boiling point,” the banking collapse was well underway.

The consequences as we can see from the examples above have been nothing short of calamitous for the economy, the wider business imperative and indeed for many governments. Arguably, many of us are still suffering from the aftershocks of the 2007-8 financial crisis.

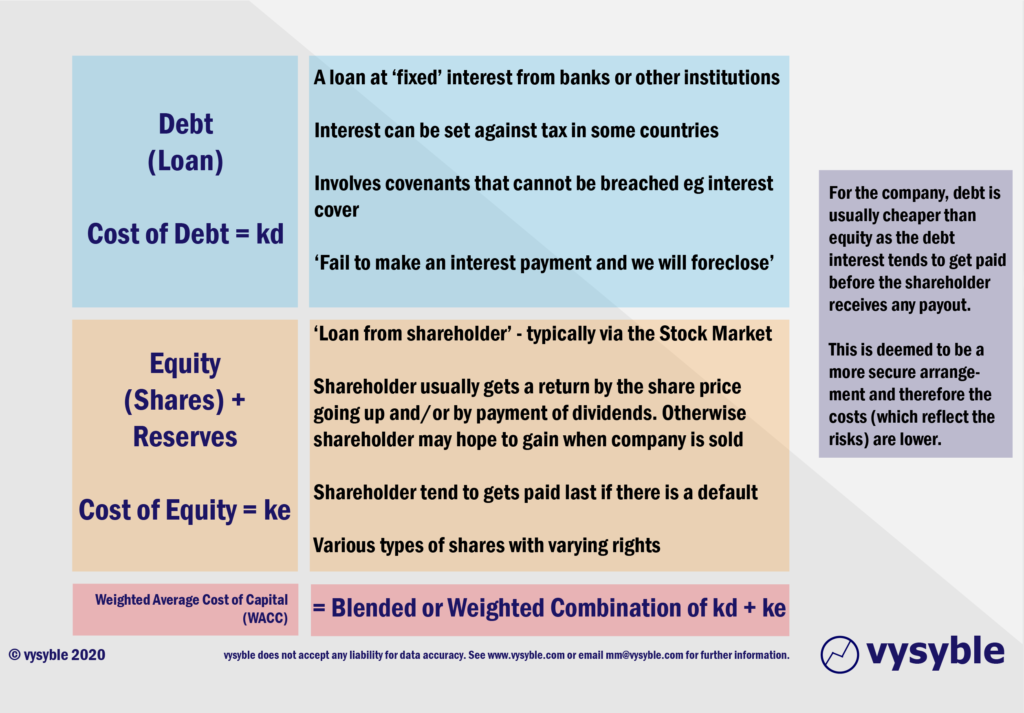

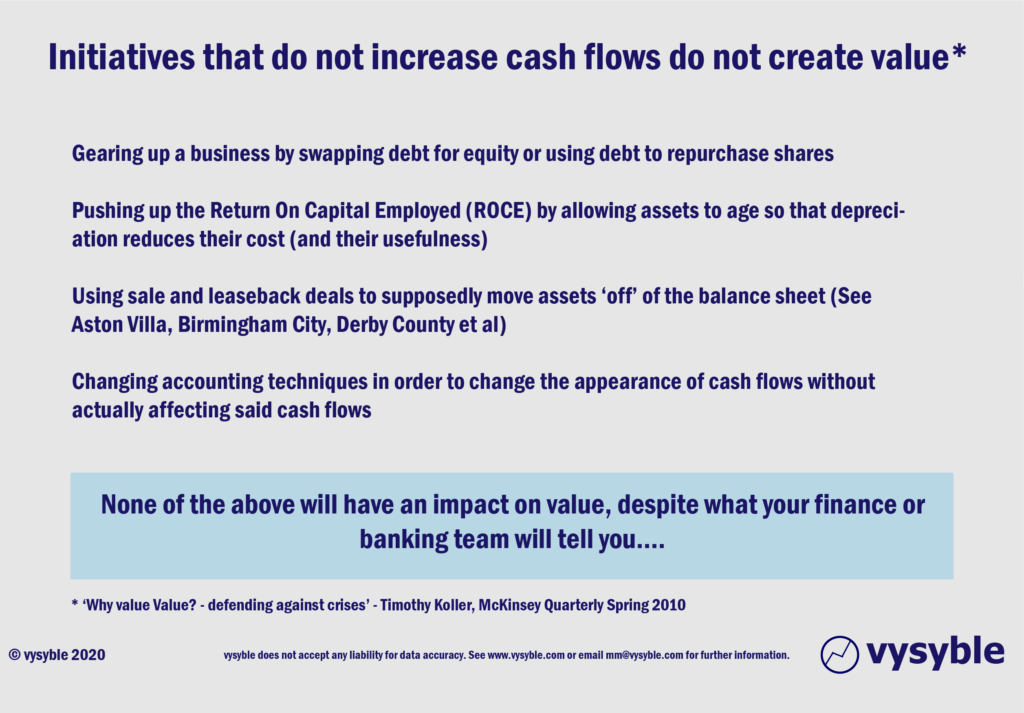

Part of the problem is that whilst most rational and sane individuals can agree with Marshall’s value-defining principle, modern financial accounting does not comply with or meet its criteria. Why? For perfectly legal reasons, most of which were conceived just after the Industrial Revolution, accounting profit takes the perspective that equity capital, often the most expensive form of finance, is “free.”

So, what is equity capital? It is the amount of money paid into a business by investors in exchange for common or preferred stock. This represents the core funding of a business, to which debt funding (eg loans) may be added.

In football, one of the most common methods used to fund the club is to invest money directly in exchange for additional shares. Indeed, an owner may also initially loan the club an amount of money for a period of time before converting the loan amount into shares. In our view, both methods come with a cost.

In the late 1950s the economists Modigliani and Miller were awarded the Nobel prize for confirming what many knew was obvious in that equity capital is not free. More to this point, they also put forward a method to calculate its cost known as the Capital Asset Pricing Model. This is the algebraic representation of risk and return.

Unfortunately, strategic decisions based on accounting data run the risk of giving the wrong signal regarding the valuation of strategic alternatives. Hence management teams frequently have a misleading view regarding the fundamental economics of the business.

“Internal management misconceptions, not external competition, are the most significant impediments to improving shareholder value.”

Jim Kilts, former Chairman and CEO of Gillette, President and Chief Executive of Nabisco and President of Kraft

Further issues with Accounting Earnings

“Accounting profits” often overstate the level of value creation. Consequently, when the capital markets fail to produce the encouraging response to the share price that the management team might have expected, the familiar but frequently incorrect phrase “The capital markets do not understand our strategy” is often heard.

The more challenging truth is that all too often the capital markets perfectly understand the strategy and are actually unconvinced of its longer-term value creating potential.

However, in a desire to show the capital markets that they “can take the hard decisions,” management teams often double-down on the original strategy of (say) cost cutting. Invariably following several rounds of diminishing costs, the market may reach a view that the given strategy cannot be delivered with what has become a dangerously low cost base. Thus, the share price falls again… In other words, the management team needs to stop pedalling so hard with the current strategy and look for a “new bike”.

This is not a small challenge or issue. For many successful and hard-working executives the idea that the key metrics and data that they have been previously using are fundamentally flawed is often a challenging issue.

The truly great CEOs like Sir Brian Pitman at Lloyds Bank or Sir John Sunderland from Cadbury Schweppes actually thrived from the ideas and strategies which flowed from a true understanding of their respective organisation’s economics, despite an initial period of consternation and denial when the economic profit data was first presented.

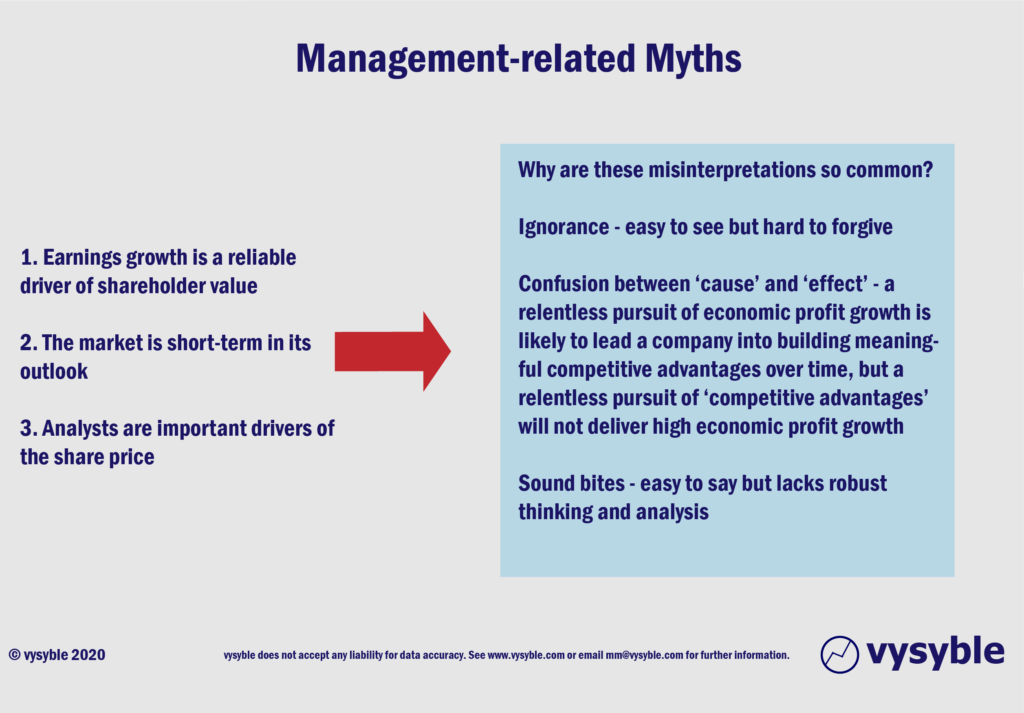

It is not an intelligence issue but one of awareness, particularly with regard to business education. With the possible exception of the University of Strathclyde School of Business, MBA schools in general have a lot to answer for in their misunderstanding of the real drivers behind value creation and destruction. The subsequent transfer of these erroneous observations and myths to their fee-paying students ensures the wide circulation of misinformation. Indeed, many MBA students end up as stock analysts and fund managers.

Warren Buffet’s views on the abilities of analysts and their observational skills are straightforward…

“I never talk to brokers or analysts. Wall St is the only place that people who ride to work in a Rolls-Royce get advice from those who take the subway.”

“The only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good.”

Buffet’s business partner, Charlie Munger, did not hold back when recently giving his opinion about EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation)…

“Think of the basic intellectual dishonesty that comes when you start talking about adjusted EBITDA….”

Other harmful myths include:

And we should not forget…

An Economic Perspective

Faced with these issues and challenges, a number of organisations have adopted an economic perspective on performance.

“Creating economic profit is the single most important driver of the stock price of the Coca-Cola company”

Roberto Goizueta, former Chairman and CEO of the Coca-Cola Company

Or to put it another way…

Ideally, in any consultancy or value audit we would seek to uncover the following pointers;

We do not believe that a business will be able to find a value-maximising strategy without a robust understanding of its economic engine room. Accounting metrics, which we readily admit have other purposes, falls short in this regard.

To be completely clear, the economic profit calculation is the monetary amount by which the organisation’s annual earnings exceed the return on capital required by investors who assume the risk of supplying the equity used within the organisation, ie Marshall’s definition of value creation. Furthermore, the economic profit measure contains an income statement metric, a related balance sheet measure and an external capital market perspective – all in one number. This unique combination gives Economic Profit (EP) a signalling quality that is vastly superior to other financial metrics.

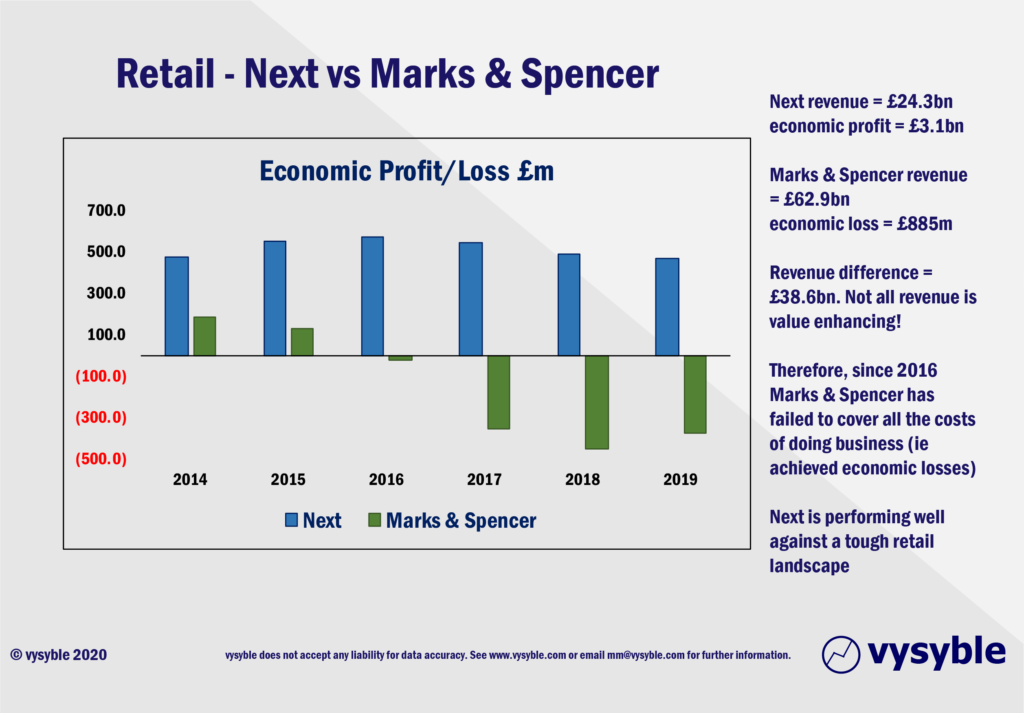

Some examples…

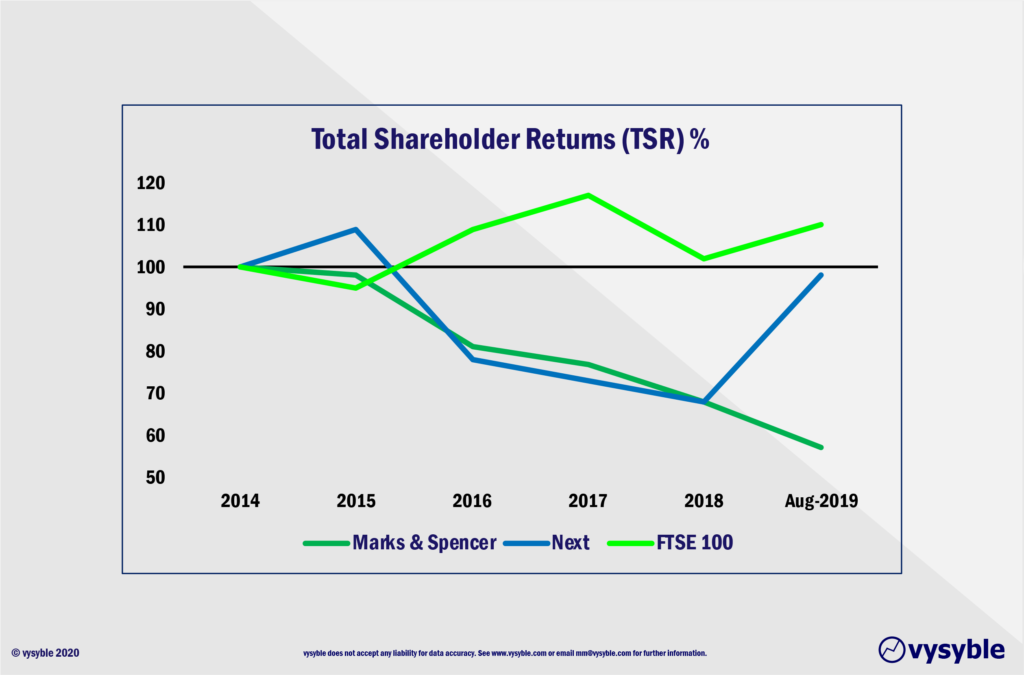

Clearly the strategies adopted by the Next management team have produced excellent numbers and the capital markets have eventually rewarded the company with a significant uplift in the value of the company’s shares.

We can see this dynamic reflected in the performance of Total Shareholder Returns which factors in all capital gains and dividends generated by a stock to an investor.

Both graphics show that Marks & Spencer is a troubled business and is clearly struggling with both long-standing issues as well as having to adapt to a very challenging retail environment. The management team, despite impressive credentials, has not convinced the capital markets and other stakeholders that it has the correct strategy for recovery.

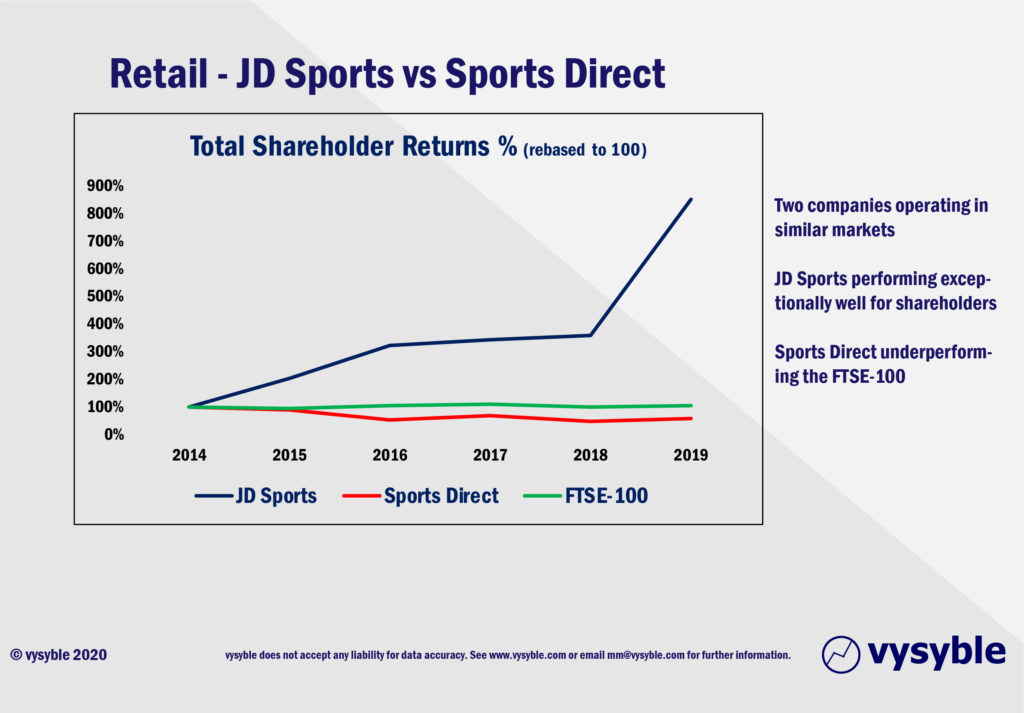

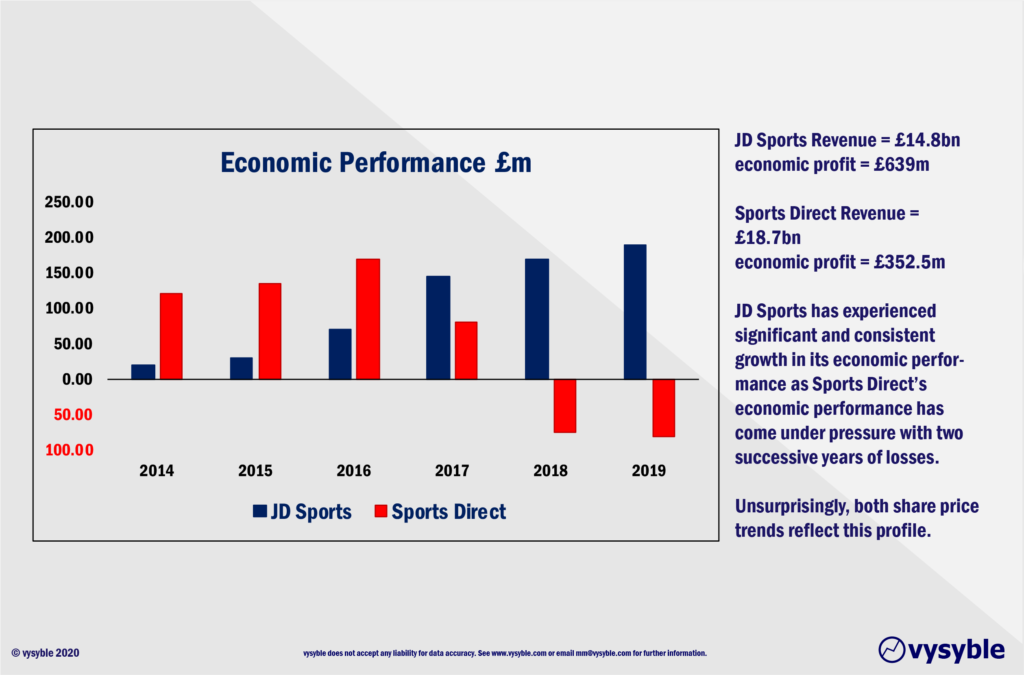

Sports Direct and JD Sports

And below is the economic profit performance – over the period 2014 through to 2019.

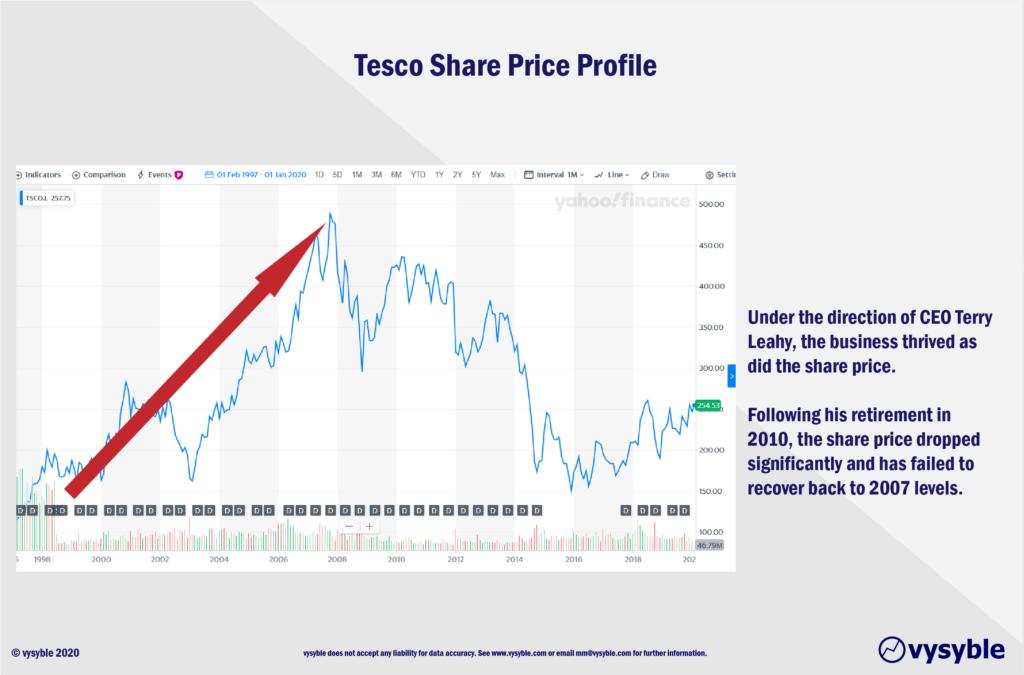

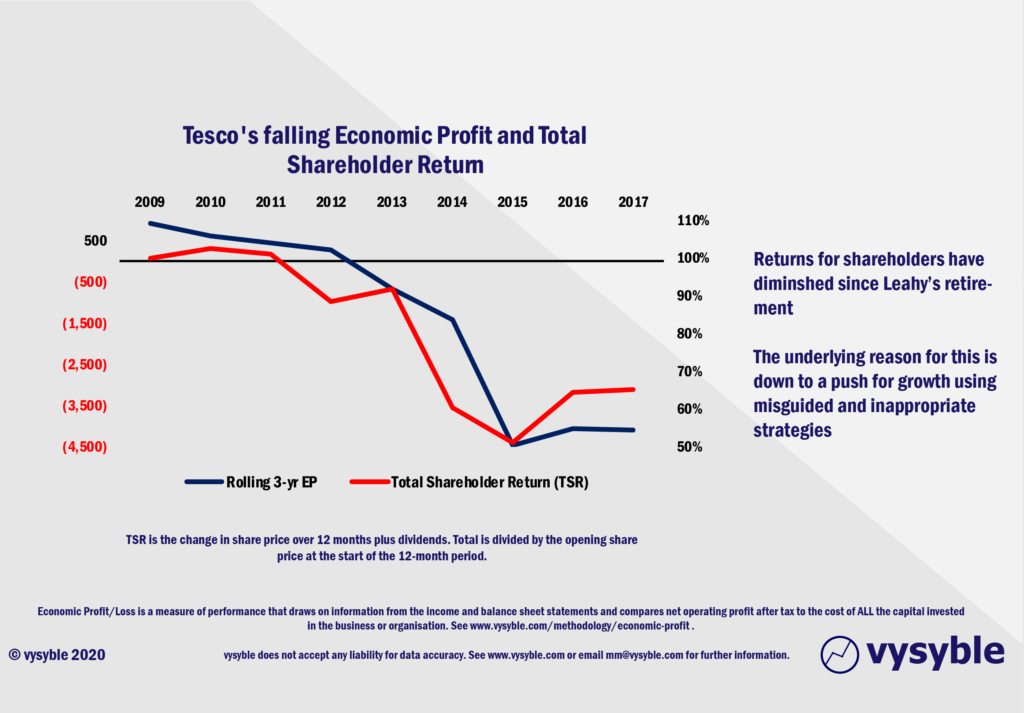

Tesco

With the possible exceptions of wine, politics and driving, it is difficult to think of a business story over the last 10 years where there has been so much misinformation inflicted on a poor and unsuspecting public. The conventional narrative is that Tesco’s decline started in 2014 as a result of Aldi and Lidl entering the UK market. Given the scale of the Tesco’s collapse and our insight into the fundamental economics of the business, nothing could be further from the truth.

Tesco’s decline actually started in 2010. The rolling three-year economic profit peaks in 2009 at £906m before falling to £617m in 2010. By 2014, the rolling three-year economic loss had increased to £1.4bn.

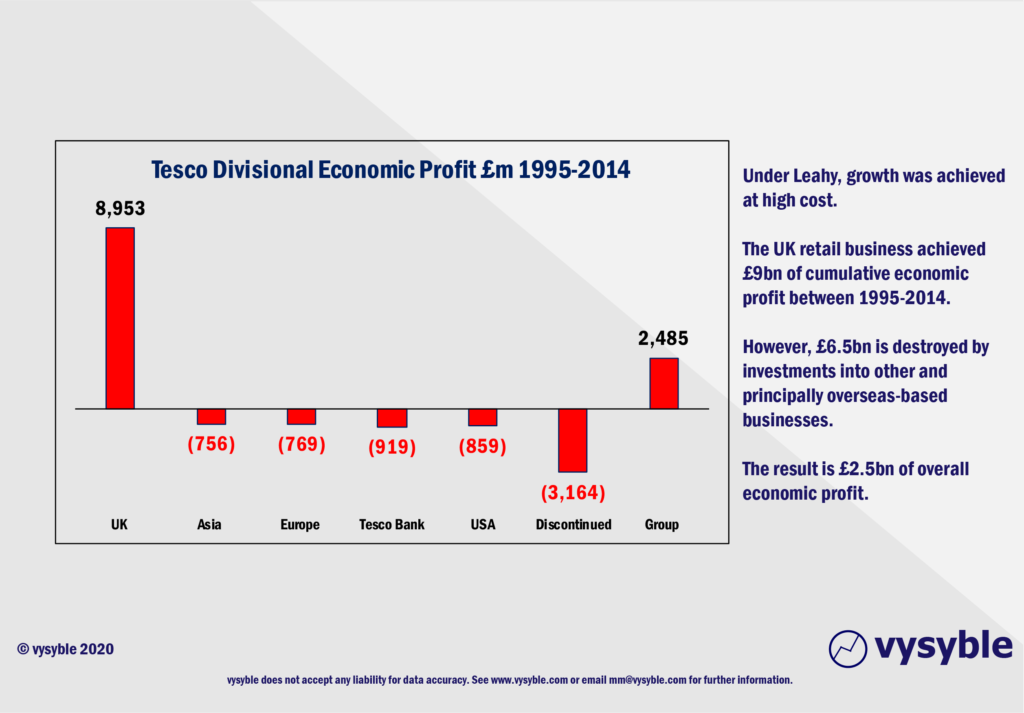

When we apply the EP metric over a 20-year period from 1995 through to 2014, the resulting picture is not one that would appear to be driven by the German discounters.

As the above graphic highlights, most of the non-UK and non-supermarket retailing activities were destroying value by approximately £6.5bn over the 20-year period whilst Tesco’s UK supermarket business was performing very well indeed.

The share price on the date of former CEO Phillip Clarke’s departure on 21 June 2014 was £2.89. Just over four and half years later in January 2019 the share price stood at £2.50, some 39p (13.5%) lower than the level deemed ‘unacceptable’when Clarke was asked to leave the business.

The prevailing comment from the media has been that the business under Clarke’s successor, Dave Lewis, had recovered but the share price would appear to be telling a very different story.

Just by way of background, at the beginning of 2010 the share price was £4.28. At the time of writing (February 2020) the share price is £2.54.

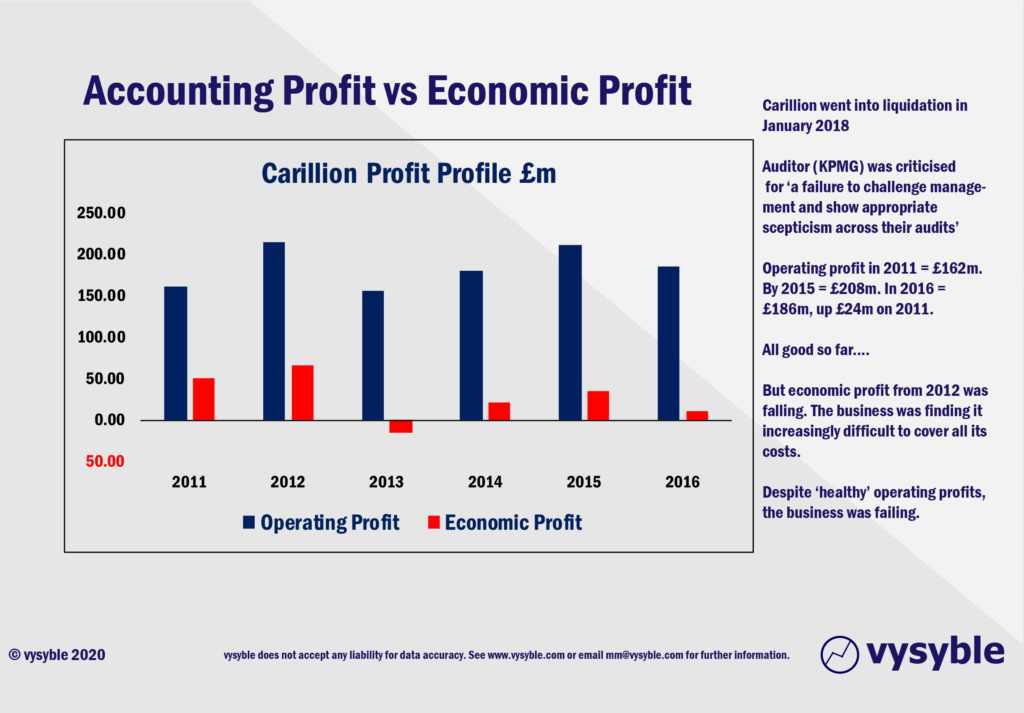

Carillion

We believe that if Carillion’s Board of Directors, the Government and even the company’s auditors had looked at the business through an economic lens then perhaps some very different and significant decisions could have been made with very different results.

Unfortunately, the company’s annual shareholder reports highlighted a near-pathological fixation on revenue but failed to point towards any value-creating strategies for the business. As the Board of Directors eventually discovered, chasing revenue comes with a cost which, if left unchecked (and it was), can be too much to bear…

Football

Here are a few statistics regarding the English footballing landscape…

51 clubs have played in the Premier League and/or the English Football League (EFL) Championship division between 2014-18.

This equates to 255 individual balance sheets.

Only 68 of the 255 balance sheets achieve economic profit.

That’s just 27%.

Total economic losses between 2014-2018 = -£1.84bn

Our blog output, press release and media history has continually highlighted our heightening concerns about the financial and economic state of English football.

Incorrect strategies

Business strategy is an important subject – for serious people interested in achieving concrete, measurable and important economic objectives.

“Yet most of the theory and practice of business strategy lacks a sound economic foundation. The strategy literature contains strong presumptions, stated and unstated, that by pursuing certain seemingly desirable goals, such as increasing customer satisfaction or by achieving economies of scale, good or improved economic results for the business will naturally follow. Unfortunately, many of these widely accepted presumptions are myths: unproven, unreliable, and often incorrect guides to good strategic decision making.”

Pete Kontes – The CEO, Strategy & Shareholder Value, Wiley

Good strategic management rests upon a number of things but a thorough and robust understanding of the fundamental economics of the business and the competitive environment is vitally important.

We have seen what the macro consequences can be when markets confuse earnings growth, market share or some other notion with value creation.

At the more micro level, the consequences of ignoring Marshall’s principle can be equally pernicious. Without a firm handle on the fundamental economics of the business the following challenges or developments will undoubtedly emerge:

- Management will not see the business as it truly is and consequently will, in all likelihood, have priorities misaligned with its continued health. The business will invariably focus on the wrong priorities and probably in the wrong order.

- Will allocate “capital,” to business divisions that are consistently destroying value.

- Will reward managers and management for pursuing strategies (e.g. earnings growth) which are poorly correlated with generating value.

- Will persist in strategy and strategies that are too generic for specific markets – what might lead to value creation in say the USA may not work so well in Europe or Africa eg different customers, regulatory regimes, taxation structures etc – and yet so many businesses deploy a “one size fits all” approach.

- Will apply a “search for growth” strategy to areas of the business in dire need of a profitability strategy, often resulting in even higher value destruction.

- Will apply a “profitability” strategy to areas of the business where “the search for growth” should dominate.

- Will fail to understand the difference between good growth, which covers ALL of the costs of doing business and which generates wealth for the shareholder, and bad growth which destroys value (i.e. is positive from an accounting perspective but economically negative)

- Will be inclined to persist with or “double-down” on strategies that are patently failing.

- Will focus on short-term priorities at the expense of longer-term value-creating opportunities.

- Will listen to “advice” from banks and other institutions in the belief that they are there to support the business. In our experience, this is not generally the case.

- Ultimately will fail, leaving customers, suppliers, employees and other stakeholders desperately looking for alternatives.

When an organisation is consistently generating economic losses, the dynamic is one of wealth being taken from the organisation and given to other stakeholders.

Much of our work on football finance has uncovered alarming and consistent economic losses for most of the clubs within the English Premier League and the Sky Bet Championship. Football’s dynamic is a simple one. A club takes resources including gate receipts from fans, revenues from television and other commercial activities and hands those resources (and more) to the players and their agents.

The quest for glory, or more commonly for survival, comes at the cost of regular capital injections by owners, high-priced short-term loans to finance the ever-increasing costs of player acquisitions and increasing financial ‘dominance’ by just six clubs (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur). All of this is compounded by regulatory oversight which does not reflect nor recognise the economic realities of the game.

Indeed, for any regulatory body we believe that it is an imperative to fully understand the market(s) that it is charged with overseeing. Without a thorough and robust perspective – and this includes a thorough value analysis – any recommendations that may be forthcoming are likely to be well-intentioned but ultimately counter-productive.

Beware of false profits.

Follow vysyble on Twitter